Genes hold secret of shipwrecked Anglesey bone setter

- Published

In the 18th Century, a mystery shipwrecked child who could not speak a word of Welsh or English washed up in Anglesey - and helped to revolutionise Western medicine with never-seen-before bone-setting skills.

Ever since, at least one in every generation of his descendants has worked in the field of orthopaedics, with his great-great grandson going on to save tens of thousands of lives on the western front in World War I.

Now 21st Century DNA technology is starting to solve the almost 270-year-old mystery of from where the boy known as the first Anglesey bone setter had been travelling.

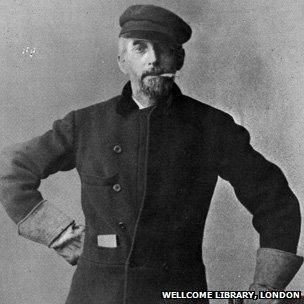

Hugh Owen Thomas, the great-grandson of the shipwreck survivor Evan

The boy and his brother found themselves the only survivors of a shipwreck off the north Anglesey coast, sometime between 1743 and 1745.

The boys' dark skin and foreign language led people at the time to speculate that they may have been Spanish.

However, DNA analysis of Thomas "Dafydd" Evans - a direct descendant of the male line - now seems to question that assumption.

John Rowlands, the project director, said: "It's been a long and sometimes difficult road, but we are now embarking on the enormous task of analysing 300 gigabytes of DNA data - equivalent to some 300 copies of the entire Encyclopaedia Britannica."

"The project has already determined that Evan Thomas (the first bone setter) is most likely to have originated in eastern Europe. A British origin has been ruled out, and the long-believed Spanish origin now also seems very unlikely."

Wherever it had begun, the two small boys' mystery voyage ended when they were rescued from stormy seas in the middle of the night, by a smuggler called Dannie Lukie, from Llanfairynghornwy on Anglesey.

He took the boys to a local doctor, but one died shortly afterwards.

The other, named Evan Thomas by the doctor who adopted him, began to take an interest in the doctor's work, and soon demonstrated a truly extraordinary skill.

First exhibiting his foreign talent on injured animals, Evan Thomas used touch alone to feel where bones were broken, and would deftly manipulate the edges to ensure a better join when the fracture began to knit.

He was also the first to use traction and splints to pull apart the over-lapping edges of breaks, and immobilise limbs while healing took place.

Healed

His techniques, unheard-of at the time, continue to form the basis of orthopaedic surgery to this day.

Robert Jones, Evan Thomas' great-great-grandson, reduced deaths from fractures in World War I

However, possibly even more remarkable than Evan Thomas' own legacy, was that of his eight generations of bone-setting descendants, who have dominated the discipline for two and a half centuries.

Each of Evan's children and grandchildren possessed the knowledge, and healed both commoners and gentry across north Wales.

But it was his great-grandson, Hugh Owen Thomas, who would find worldwide acclaim as the "father of modern orthopaedics".

Hugh Owen Thomas, the first of the dynasty to be formally trained as a physician, invented the Thomas Collar to treat osteo-tuberculosis, the Thomas wrench for reducing dislocations, and the Thomas splint, which greatly reduced deaths from femoral fractures among late 19th Century Liverpool dockers.

'Very exciting time'

However the full significance of the Thomas splint wasn't realised until it was employed on the western front by Hugh's nephew Sir Robert Jones, (Evan Thomas' great-great-grandson), where it reduced fracture deaths from 80% in 1916, to just 8% by the end of World War I.

Not that Sir Robert had to rely solely on his uncle's inventions. In February 1896, he hit the headlines when he became the first doctor in the world to use X-Ray photography to diagnose a fracture.

He was also the co-founder of what is now known as the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital in Gobowen.

But after two-and-a-half centuries amongst the bones, Dafydd Evans explained that the family tradition may now finally be coming to an end.

Robert Jones operating in the early 1900s

"My sister is a radiologist, and my cousin in Australia is a doctor, but they're about the last of us," said Mr Evans. "I'm a retired headmaster."

"I suppose that's why it's so important now, to finally find out where these extraordinary skills came from."

"Family legend always had it that Evan Thomas came from Spain, but I think that was pretty much guesswork, because of his dark skin and the fact that so many Spanish ships at the time were heading past Anglesey for Scotland to take part in the Jacobite rebellion."

"With so many generations excelling in the field, you have to say it's in our genes, but the way in which the skills have been passed down from father to son and daughter is very much part of their Anglesey upbringing."

A full analysis of the DNA will not be available until later next year but John Rowlands is hopeful that the final results may even be specific enough to pin down a precise location from where these extraordinary skills once came .

"This is a very exciting time, as we move ahead, possibly to a stage where a village, and even a family surname can be located that tells us where Evan Thomas came from, and perhaps why he was on a ship sailing past the coast of 18th Century Anglesey."

"The power of modern science really is remarkable when you consider that we are getting to the bottom of this story more than 260 years after it happened."