Art to help heal Penrhyn Castle's slate strike pain

- Published

An art project hopes to heal emotional divisions still felt in a slate community, more than a century after Britain's longest industrial dispute.

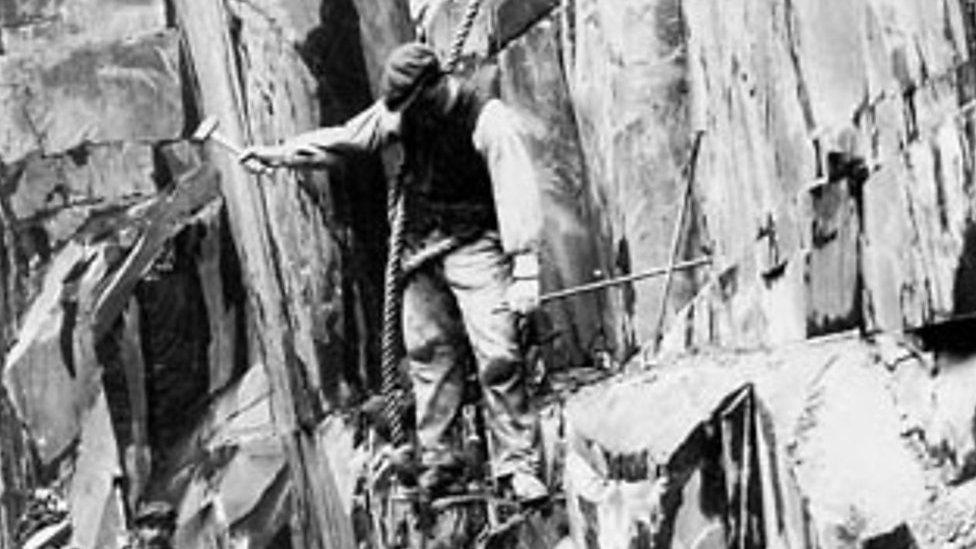

Thousands of men were locked out of the Penrhyn slate quarries in Gwynedd after a mass walkout in 1900.

Artists will recreate a representation of the quarries in the former owner's home - Penrhyn Castle, outside Bangor.

The National Trust said it was part of re-evaluating how it deals with the castle's "darker" history.

"It's time - it's well over time that we are telling this story," Rhian Cahill, the National Trust's visitor experience manager at Penrhyn Castle, said.

"We need to bring that reality in here and show it.

"About 80% of our visitors are tourists, and they don't know anything of the pain, or any of the real stories of how the fortune came to Penrhyn - well, now we are going to say it."

Rhian Cahill said: "It's time to tell the stories"

SLATE AND SLAVERY

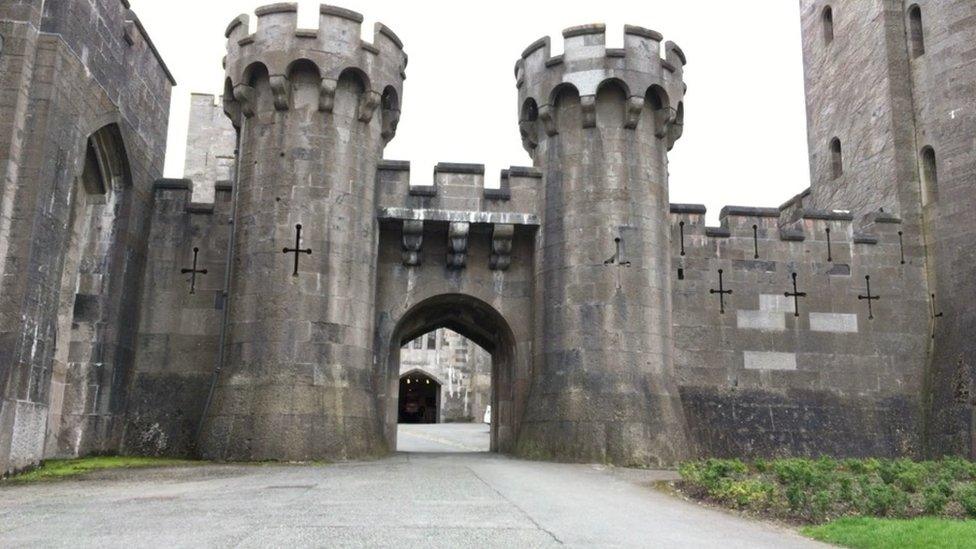

With the Menai Strait and Conwy Bay on one side, and the rising slopes of the Snowdon range and the Carneddau mountains on the other, Penrhyn Castle was built to make a statement - it was all about opulent wealth and grandeur.

But it is a relative newcomer - an upstart even. A stone's throw away, the city of Bangor can date its foundation to the 6th Century. Penrhyn Castle and its lush wooded estate - it was built in the 19th Century - a fantasy palace with a stone facade that hides its internal red brick construction.

It was the vision of George Hay Dawkins, who inherited the estate - along with Jamaican slave plantations - from his cousin, the original Baron Penrhyn, Richard Pennant, in 1808. The castle passed to his daughter on his death in 1840 - and then to his son-in-law Colonel Edward Gordon Douglas when she died in Italy just two years later.

Edward Douglas went on to entertain Queen Victoria at Penrhyn in 1859 and in 1866 was elevated to the peerage as the first Baron Penrhyn of Llandygai.

But it was his son who cemented the slate fortune - both its rise and fall.

Slate quarry strike: Art bid to heal divisions

Records show George Sholto Gordon Douglas-Pennant earned £133,000 in 1899 from his slate quarry operations - about £13.5m at today's value - or an estimate economic worth in present terms of about £138m.

But a year later, prompted by a simmering row over pay and conditions, some 2,800 quarry workers in Bethesda walked out - sparking the Great Strike.

The strike divided the community, with those refusing to work displaying placards in their homes declaring in Welsh: "Nid oes bradwr yn y ty hwn" (No traitors in this house).

It was instrumental in developing both the trade union and Labour movement across Britain but ultimately it was a failed dispute.

By the end of the strike in November 1903, the workers had been crushed. Lord Penrhyn refused to budge on their demands. Those that had not already left for work in south Wales and beyond, including America, returned to work.

But the impact of the strike on the quarry was body blow from which it would never really recover.

While the gates to Penrhyn Quarry were shut, other sources of slate were found. And then in the decades to follow, World War One, the Great Depression and World War Two.

It was a period of decline for the industry, and for communities like Bethesda, that had once relied on the work the Penrhyn Quarry offered.

A painting of Penrhyn Quarry at the castle is one of very few reminders about its history

Renowned installation artists Walker & Bromwich have been chosen to bring together the latest project at Penrhyn Castle, the third year the Arts Council of Wales has funded a residency at the venue.

The pair - Zoe Walker and Neil Bromwich - have had work on show at locations such as Tate Britain and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Australia.

They have been hosting a series of community workshops in the former quarrying town of Bethesda, six miles away (10km).

Fittingly, the venue where residents have been getting involved is Neuadd Ogwen. In a former life it was the location for the town's market, where striking quarry workers held many of their meetings.

Inside, tasks under way include making political marching banners and intricate templates for the quarry "sculpture".

In fact, the sculpture will be a massive inflatable version of the 19th Century Penrhyn Quarry, and when it is finished it will be marched to the gates of the castle by the town's choir, before being blown-up inside the castle - filling its great hall.

Walker & Bromwich have been working on the project since 2016

Painstaking work under way to make a model that will be scaled to fill the Great Hall in the castle

Banners will play an integral role in July's events

"It was made clear to us pretty early on that there is still a huge animosity from members of the local community, particularly in Bethesda, towards the castle," Mr Bromwich said.

"There are people who have said they will not cross the threshold and go there.

"The pain from over 115 years ago is still felt within communities - it really tore this community apart through the suffering and the deprivation.

"The work aims to being to acknowledge what happened."

For the other half of the artistic duo, this not just about reconciliation.

"I think for us it was important to create something that celebrates the community - the strength of the community," Ms Walker said.

"Those quarrymen and their families who went through that - to celebrate them, and to create this kind of act of celebration of what they did."

Recognition "long overdue", says artist Rebecca Hardy-Griffith

They are being supported by local artists such as Rebecca Hardy-Griffith, who said she was delighted to be involved in a "brilliant" project.

"The idea of having that representation about the Great Strike in the castle is such an important one. It is one that is still missing - and it is 2017," she said.

"It's about time that we put this story to people in the castle and that it is represented.

"Although there is political, heart-wrenching history, there is celebration in there as well - how well the community came together, how well the community is now."

The final procession to the castle with the completed quarry sculpture will take place on 1 July.

In the meantime, community workshops by the artists will continue to be held in Bethesda and at the castle - including a day event on Saturday at Neuadd Ogwen.

- Published15 April 2017

- Published15 April 2017