Epynt village clearance: Woman remembers, 80 years on

- Published

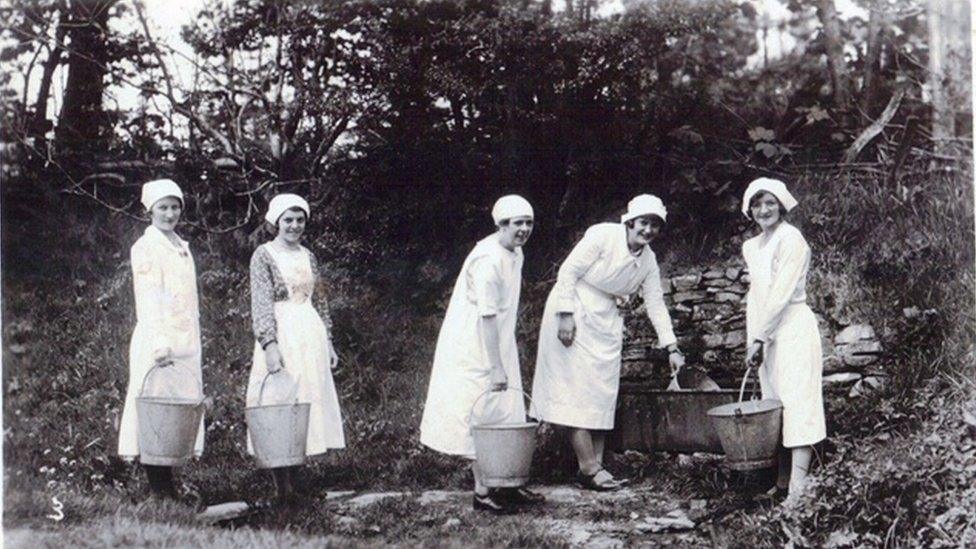

Farm life on Epynt before the clearance in 1940

"We have to keep telling this story so that it doesn't happen again."

Rachel Lewis-Davies farms with her husband Bobby at the foot of the Epynt mountain near Trecastle in Powys.

Her family connection to the area is strong, and she's proud of her roots.

But it has taken years of research to piece the family's story together and discover what happened to her relatives 80 years ago, when the Army came to Epynt and the War Office requisitioned their farm.

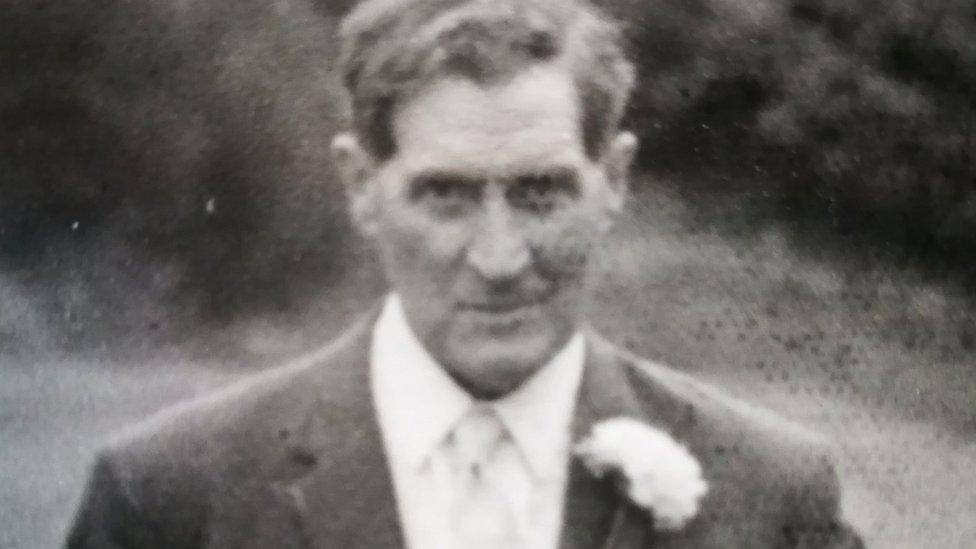

Her grandfather, Evan Rees Lewis, lived at Abercriban farm with his father and three brothers. Their mother died of TB when they were young.

The family were given notice and had to leave their home after the War Office decided the land was an ideal area for artillery practice.

They weren't alone - in total, 54 farms and a pub were vacated in what's become known as the Epynt clearance.

More than 200 men, women and children had to leave their homes and community.

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) said their sacrifice allowed important training which contributed to the Allies' victory in World War Two.

Evan Rees Lewis was among more than 200 people who were forced to leave their homes

Rachel Lewis-Davies returned to farm the area her family left in the 1940s

The Army acquired 30,000 acres in total on and around the Epynt Mountain.

Locals were told it was part of the war effort and many thought it was done with an understanding that the arrangement was temporary and families would be able to return after the war.

Rachel has heard a local story that fields were ploughed at Abercriban in the Spring of 1940, in the belief that they would return to the farm.

But that never happened.

The Army is still there today and the area is now called Sennybridge Training Area.

A timetable for live firing is published every month by the Ministry of Defence and they take place every day except two this month.

There's even a mock village on the ranges.

It was built in the late 1980s in the Cilieni Valley and is based on a typical small German village.

It's known as a "ghost village" and is still used today by soldiers for Fighting in Built Up Areas (FIBUA).

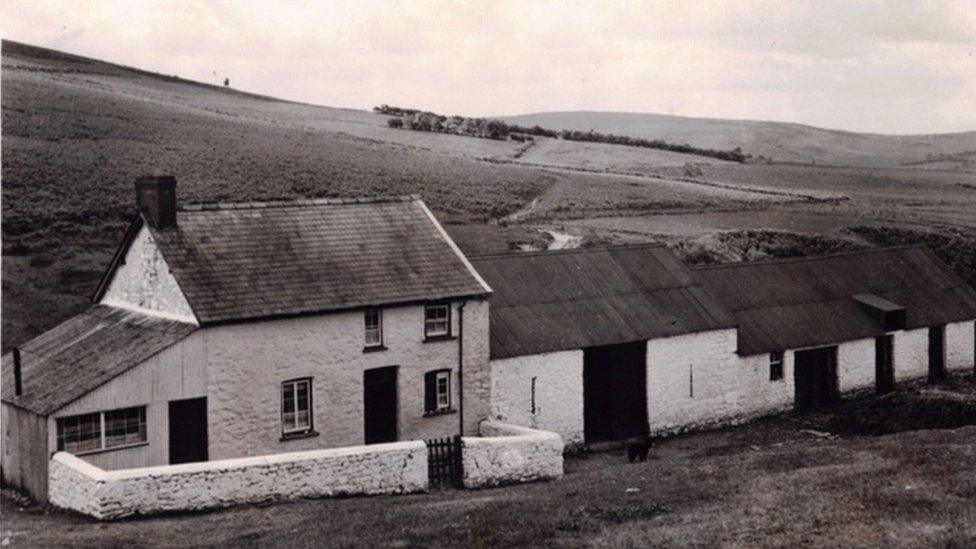

Gwybedog farm, which was vacated in the clearance

Many of the original buildings, including the farmhouses, have been destroyed.

As well as losing their homes, there were other losses for the community.

Welsh had been widely spoken by people living in the area, but the language virtually disappeared when the farms were abandoned and the people uprooted.

"The Army would refer to the farms by number, not by name... and Mynydd Bwlch y Groes became Dixies Corner," says Rachel.

"But the names are important - Llwyn Coll, Gilfachyrhaidd, Waunlwyd, Abercriban, Cwm Car - it's vital that we remember them."

Evan Rees Lewis was 24 when he left Epynt and moved with his youngest brother, Mordecai, to Painscastle, married a local woman and had three sons of his own, including Rachel's father, Arthur Rees Lewis.

Rachel and Bobby were desperate to farm themselves and managed to get a council farm in Ffynnon Gynydd, near Glasbury on Wye.

Until 2002, the Army was still buying farms in the area and at about that time, land with grazing rights on Epynt became available at Spite Inn near Tirabad.

The couple were successful in securing the tenancy, which meant Rachel could finally return to farm the mountain where her grandfather grew up.

"I feel that I'm hefted like the sheep we farm - I've returned to where I'm meant to be," she said.

"Epynt is central to my daily life, our Epynt flock is an integral part of our farming business.

"I made sure my three children went to a Welsh school, bringing the language too back into our family."

Farmers were forced to leave their homes and land when the Army requisitioned the area

Rachel has also worked with fellow farmers to campaign for a native breed of sheep to be officially recognised, and the Epynt Hardy Speckled breed now has its own breed society.

She says the name Epynt needs to be kept alive otherwise the area will only be known for its military connections.

But there are mixed feelings among people in the area who want the story to be remembered but have also learned to adapt to the arrangement.

Rachel admits the tenancy of Spite Inn has been central to the family business: "Opportunities for people like us who want to farm are limited without the tenanted sector.

"We are grateful to the Army for the opportunity. What happened here 80 years ago has relevance to Welsh farming and rural communities today.

"The Welsh uplands are still under threat today due to changes of land use like large-scale afforestation and rewilding - and we need to protect them.

"What happened here was done in the national interest, but these communities have value and are an important part of Welsh rural life."

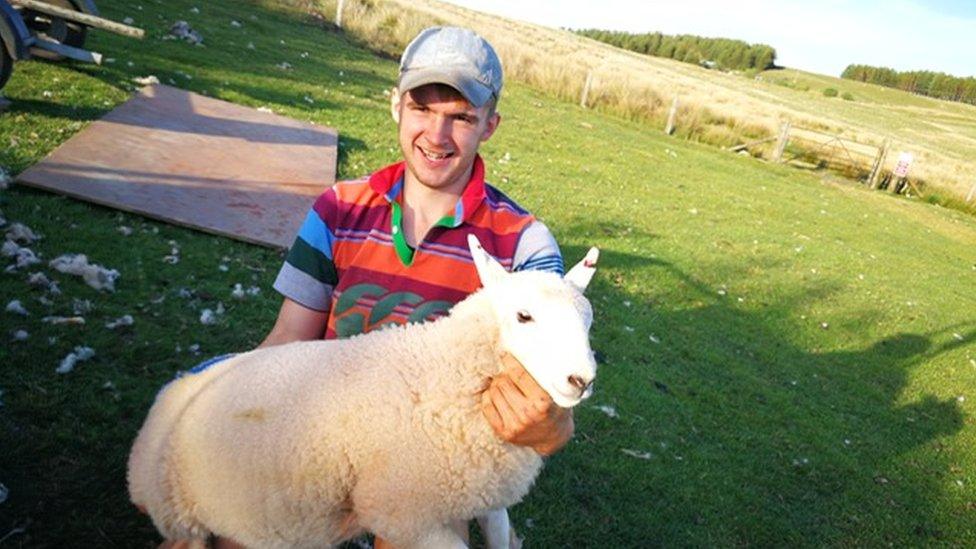

Lewis Davies, 20, Rachel’s son and great-grandson of Evan Rees Lewis

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Epynt Clearance.

The peace group Cymdeithas y Cymod is tweeting the name of a lost farm every day, external this month as well as sharing poems to highlight what it describes as the "ongoing injustice of a community sacrificed to the military".

Rachel says many people are unaware of the history of Epynt: "Evan Rees Lewis was one of 220 men, women and children uprooted from Epynt 80 years ago.

"I am just one of Evan's 42 descendants with my own part of the Epynt story to tell."

An MOD spokesman said: "The sacrifice of those whose land was requisitioned in the Second World War to allow important training contributed to the Allies' victory.

"Soldiers since then have developed their military skills at Sennybridge Training Area which is required for operational commitments.

"The local community of Sennybridge continue to contribute to the management of the land through sheep grazing, wildlife and nature groups."

- Published21 October 2015

- Published20 June 2018

- Published30 July 2017