Merthyr Tydfil's journey from iron to a very different industry

- Published

It was once described as the iron capital of the world and while some believe it should be a world heritage site, others feel Merthyr Tydfil has simply been left to ruin.

With most of its furnaces, coalmines and factories now long-closed and unemployment high, a very different type of industry is seen as a catalyst for reviving the area's fortunes.

Millions have been spent turning the old town hall and Zoar Chapel into cultural centres, while the third Merthyr Rising festival is set to bring artists, musicians, writers and filmmakers together in June.

It is these creative industries that are seen as the potential trigger for tapping into a wealth of local talent and drawing in investment and tourism.

But for this to happen, a belief that local people are not good enough to achieve big things must change, according to Lynnette Jenkins, who left school at 16 to work in a chocolate factory.

She was on the verge of giving up a part-time theatre and media drama course when the BBC gave her positive feedback about a script she had written.

"Everyone in Merthyr underestimates themselves, but after that I believed in myself and kept going," she said.

Her defining moment came in 1999, when she saw an advert in a newspaper asking for writers to submit ideas for a new HTV drama set in the valleys.

The Merthyr Rising festival was launched in 2014 to celebrate the town's history of radicalism and creativity

Ms Jenkins, now 45, sent her script in and Nuts and Bolts was born, which would run for four series until 2002.

"There was no regional drama at the time and for me it was the biggest thing ever. They wanted to film it in Pontypridd but I insisted it came here," she said.

"They invested a lot in local talent, it was like a university on set, with few professionals.

"In many ways it was a turning point for Merthyr and the hope and buzz it created is still here today."

While the gritty drama was axed after viewing figures dropped when it was moved to a late-night slot, Ms Jenkins is now writing a film she hopes will show the area to a worldwide audience and help stimulate economic regeneration.

"There is no heavy industry coming here now, that's never coming back. But we have a massive resource that hasn't been tapped into - the community spirit that still exists here.

"These nuggets of gold have never been mined. People have so many stories and tales that have been passed down through the generations.

"What people in Merthyr don't realise is that there is a big world out there and we can reach it - working class people can write better as they have experienced things others haven't."

To help bring out this creativity, a new workshop called I Can is set to be launched at Theatr Soar - that encourages anyone with a mobile phone to write and direct their own film.

A spoof film of Reservoir Dogs was made to promote the Merthyr Rising festival in 2015

"I think all children are creative but they lose it as they get older and are encouraged to become more mainstream," said the theatre's Phyl Griffiths.

The bilingual community theatre was created as part of the old Zoar Chapel after a £1.8m investment and hosts performances in both English and Welsh.

Mr Griffiths said the cafe at the centre is also becoming a "focal point", where artists and musicians are meeting to exchange ideas.

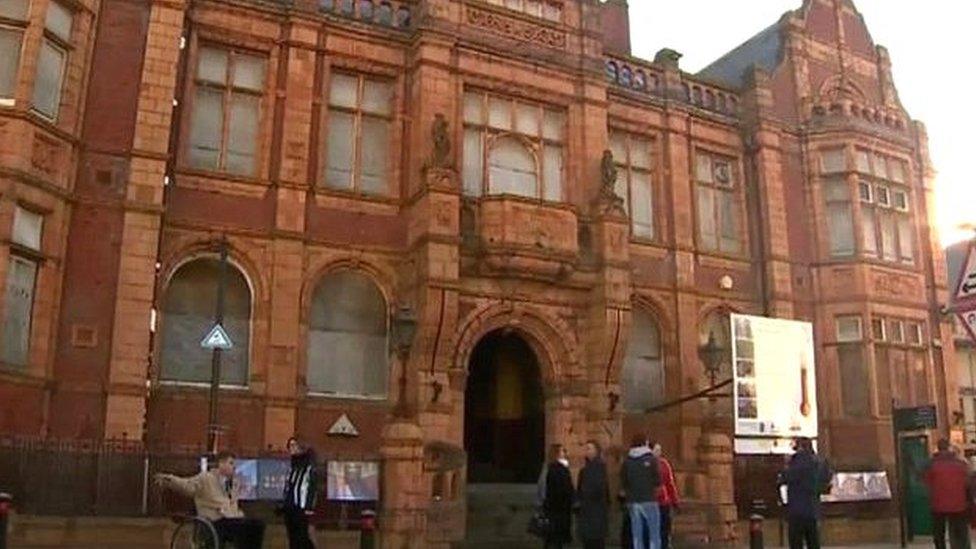

There is also the old town hall, renamed The Redhouse after a £8m redevelopment in 2014, that is being used for exhibitions and live music - with highly-rated local band Pretty Vicious playing their first gig there.

"We were the iron capital of the world, Merthyr could be a world heritage site. But it was left to ruin and is in many ways became a pretty desolate place," said Merthyr College film lecturer Mark Boucher.

"But the area is turning around, there has been a lot of investment over the last 10 years and only now is it starting to show.

"My students have won a string of awards for films they have produced. There are a lot of talented people in Merthyr and there is definitely a buzz about the place."

This has been helped after a large investment in the college after it was taken under the wing of the University of South Wales, says Mr Boucher.

He is another who left school with no great creative ambition and worked as a builder and then ran a shop.

But it was in 1999, when Nuts and Bolts producers convinced him to let them take over his house for filming, that his life changed.

Kill Phyl

"There were 30 people in my living room - sound people, cameramen, actors, directors. I just thought 'wow, I'm in the wrong job'.

"I phoned a mate and he said there was only one way into the industry - college. So, I sold the shop and started a theatre and media drama course."

As well as his lecturing work, he has helped produce a string of films and plays, including Karl Francis' Hope Eternal and Patrick Jones' The War is Dead, Long Live the War.

Along with Ms Jenkins and Mr Griffiths, he is involved in CoDu Productions, which aims to inspire local people and a wider audience.

One of its first projects is a Festival of Fear at Halloween - with bilingual talks on horror through the ages at Theatr Soar.

It will culminate in a run of stage play Kill Phyl, which has been written by local man Gareth Hunt, 38, with the production company hoping to make it into a feature film over the summer.

While Merthyr Tydfil's furnaces may no longer be burning, ambition is and it is hoped the creative industries can put the town on the map once again.

- Published1 March 2014

- Published31 May 2014