Holocaust Memorial Day: 'Kindertransport saved my life'

- Published

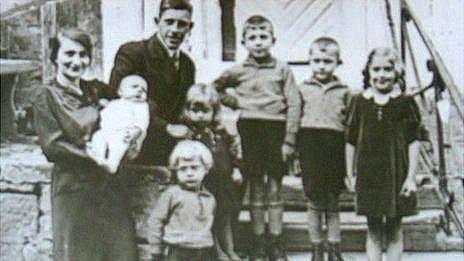

Ellen Davies (far right) was the only one of her brothers and sisters to survive after being rescued from Germany as part of the kindertransport programme

Ellen Davies was the only one of a family of seven brothers and sisters to survive World War II.

Born into a middle class Jewish family in a village in Germany, she was put on board a train and sent to the UK in 1939 as part of the kindertransport programme.

Sanctioned by the British Government, it rescued about 10,000 Jewish children from central Europe during the months leading up to the outbreak of war.

Mrs Davies, who was taken in by foster parents in Swansea, said she was in no doubt it had saved her life.

She was born Kerri Ellen Wertheim, the eldest child, in Hof, near Kassel, in 1929.

"It was a little village in Germany where everybody knew everybody else," she said.

"I lived in a big house with my parents and brothers and sisters. My grandfather was the local Jewish butcher.

"It was quiet and peaceful until 1933 when everything changed when Hitler came to power.

"We were ostracised in a big way. Children who were once friends turned their back on us, spat at us or threw stones at us. Then they took away our home."

Mrs Davies recalls one incident when she was eight years old when she and her younger brother were beaten with truncheons by members of the Hitler Youth when they tried to go shopping for food.

"Hugged and kissed"

In 1939, at the age of 10, she was placed on a train as part of the kindertransport programme.

When Ellen Davies arrived in Swansea she could not speak a word of English

It was the idea of leaders of the Jewish community in Britain, and saw Jewish children in Nazi-occupied Europe brought to the UK.

"All I remember is being hugged and kissed and my father put me on the train and locked the door," said Mrs Davies.

"I did not want to go. I was forced to go.

"I'm 83 now and I still have sight of my mother and father getting smaller and smaller in the distance. That's with me every minute of every day."

She travelled by train and boat and ended up in London.

"We had big labels on us with names and numbers - my name was called and this giant of a man took my hand and we walked out to the station and we caught another train to Swansea," said Mrs Davies.

"My foster parents were 70 and 50 and what I discovered later was they wanted someone to look after them in their old age.

"My foster father was the nicest sweetest man but my foster mother had never had anything to do with children - did not really like them or know how to treat them."

"Tough school"

She said her first years in Wales were hard as she could not speak English, missed her family and did not mix with other children.

"What you have to realise is my foster parents were old, so they did not mix with the sort of age group I would have had as parents, so I did not mix with younger children. I had nobody to bond with.

"I went to Terrace Road School - quite a tough school in Swansea - without a word of English.

"They did not know about concentration camps - they did not believe me."

When she was 15 her foster father died and she took over the running of his haberdashery business.

In later years she discovered what became of the rest of her natural family.

After a period in a concentration camp her father escaped Germany and after a spell in the Pioneer Core emigrated to Australia.

But her mother and siblings were not so fortunate and died en route to a concentration camp in 1941 at Bikerniek Forest near Riga in Latvia.

"As my mother and the children came off the cattle trucks the men who took them tried to separate my mother from the children," she said.

"My 12-year-old brother stood in front of them and said 'if we are going to die we die together' and they were shot there and then.

"My brother was 12, the youngest was two."

Closed doors

For more than 30 years Mrs Davies, who lives at Southgate on Gower, has lectured about the Holocaust and visited schools to tell pupils of her story. She has also written a book.

Mrs Davies said she has no doubts Kindertransport saved her life

Her experience forms part of an exhibition currently running at Swansea Civic Centre about Jewish refugees who came to south Wales between 1933 and 1945.

"This history is the most important thing in the world," she added.

"If you don't learn anything from the past you make the same mistakes in the future."

As well as focusing on prominent refugees such as artists like Heinz Koppel and Josef Herman, the exhibition tells the story of the Kindertransport programme.

"Kindertransport was one of Great Britain's kindest and most wonderful things," added Mrs Davies.

"America closed its doors because it had a quota, Canada would not open its doors, South American took in families - Great Britain - a small county - took in 10,000 children.

"I have wonderful children and grandchildren, so have been very fortunate," she said.

Refugees in South Wales 1933 to 1945 is on display in Swansea Civic Centre's foyer until 5 February.

- Published19 May 2011