How WW1 changed emergency medicine

- Published

L/Cpl Scott Haplin has worked as a first responder on the battlefield for three years

As the centenary of the start of the World War One draws nearer, BBC Wales is exploring how core roles in the modern British Army were first developed during the conflict.

From the introduction of gunners on tanks to signallers using radio communications, these technological advancements had far-reaching consequences on the war then and on today's battlefield.

Charlotte Dubenskij takes a present day Army first responder back in time, visiting a museum dedicated to probably WW1's most famous first-aider - the inventor of penicillin, Alexander Fleming.

It is a role L/Cpl Scott Haplin from Kidwelly in Carmarthenshire knows only too well. He has been a first responder for 1st The Queen's Dragoon Guards for three years.

In that time he has seen plenty of action as part of the Welsh Cavalry.

"On my last tour I was involved in an IED explosion when two men lost their lives. I helped the driver out of the vehicle, checked him over and made sure he got back safely for treatment," he said.

The role of a first responder is commonplace in the armed forces today, but it was only during World War One that it was realised medical expertise was needed closer to the action.

"Before the First World War there were only porters on the battlefield. These were men who picked up casualties and took them away from the battlefield to be treated," said military medical historian Dr Emily Mayhew.

"It was realised you needed expert stretcher bearers or first responders who had medical training and could treat the casualty, stop them bleeding and keep them alive until the next stage," she said.

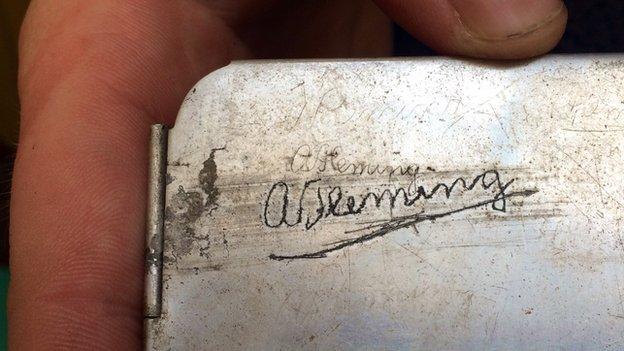

Like all soldiers, Alexander Fleming, who went on to discover penicillin, carried medical supplies in a metal tin

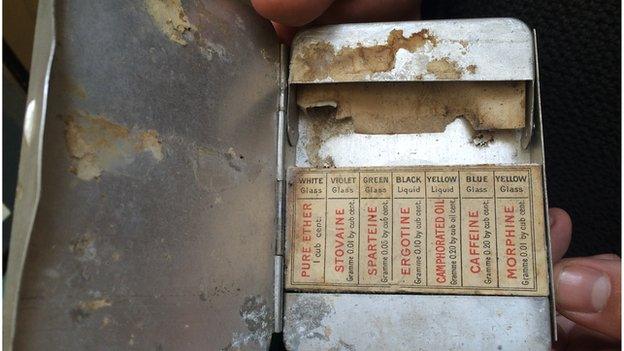

Inside a WW1 medical tin, which focused on pain relief

Dr Mayhew says the introduction of the first responder is one of the great legacies of the conflict, but despite this she says the men were often abused by the other soldiers.

"When the battalions went forward, the stretcher bearers went with them. As they all wait in the front of the trenches to go over the top and fight, quite often the soldiers will abuse them saying, 'why don't you get a gun and fight?'

"They think it's bad luck to have them there.

"But when the soldiers go over the top and are injured, when the stretcher bearers get to them the soldiers apologise as they realise what their role is."

Technological advancements have had far-reaching consequences on the battlefield

For L/Cpl Haplin that perception could not be more different today.

"Being a first responder I'm trusted by the soldiers I work with and they respect me as they know I'm there to help," he said.

As well as responding to injuries he also makes sure the soldiers he works with eat properly and are hydrated.

He carries a medical pouch containing re-hydration sachets, tourniquets and trauma bandages, and blood-stopping celox gauzes at all times.

The kit used today is a world away from that provided to stretcher bearers and field officers such as Fleming 100 years ago.

'Good war for medicine'

Kevin Brown, the curator of the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum, explained: "The men carried in their pockets this small metal tin.

"Inside it contains a number of small phials of pain relief such as pure ether, morphine and caffeine. Now at that point (WW1) it was thought the best treatment was morphia and cup of tea and a cigarette."

He describes World War One as being "a good war for medicine" with many advances in the field over the four-year conflict.

"The war saw a huge amount of innovative work on rehabilitation. Much of this was orchestrated by the British Army's expert on orthopaedics, the Welshman Sir Robert Jones," he said.

"This is the first time we see an emphasis on when the men get back home on getting them back to leading a normal life," he said. "Men who lost limbs were given prosthetics and trained in various crafts they could do to earn a living. Before the First World War they were ignored."

Other new inventions in the field of medicine included the Thomas Splint which is still used to stabilise fractured femurs to prevent infection and help knit the bones back together.

It was invented by another Welshman, Hugh Owen Thomas, who was also the uncle of Sir Robert Jones. When used in World War One it reduced mortality of compound fractures dramatically, reducing the number of soldiers who died.

"Looking back at the role then to what I do now, I think it would have been a lot harder," said L/Cpl Halpin.

But he says many of the ideas which were born in World War One are still being used on the modern battlefield. "As they say in the Army, if it ain't broke why fix it?"

In action: L/Cpl Haplin has relied on his first responder skills on deployment with The Queen's Dragoon Guards

- Published16 June 2014

- Published15 June 2014

- Published15 June 2014

- Published13 June 2014

- Published24 February 2014