UK's first heart pump targets 2018 clinical trial

- Published

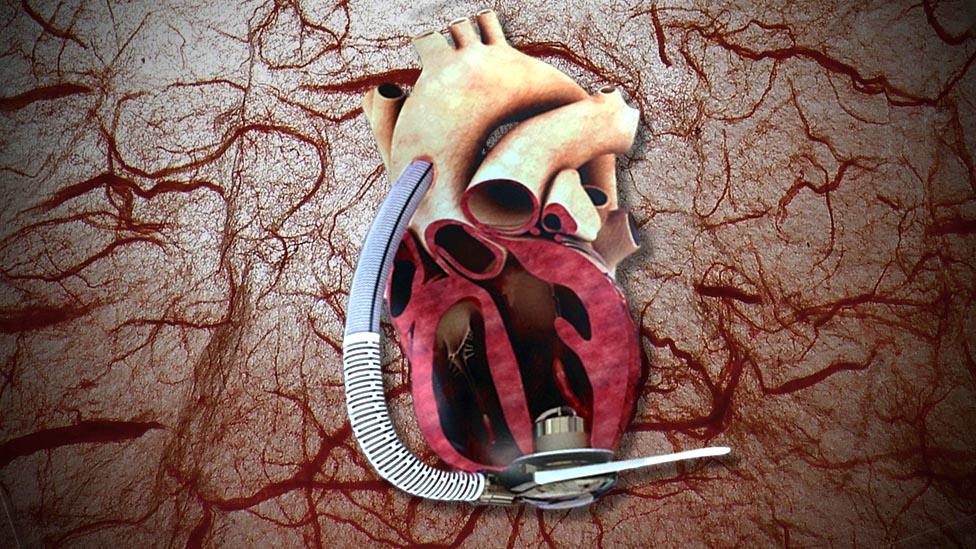

Researchers have suggested heart pumps could help solve the shortage of heart donors

The UK's first artificial heart pump has moved a step closer to being used on patients, scientists have said.

It has been developed at Swansea University's Institute of Life Science 2 by Calon Cardio, and clinical trials are due to begin in late 2018 with the aim of a full rollout two years later.

The pump is implanted into the failing heart and should last about 10 years.

Stuart McConchie, chief executive of Calon Cardio, said it was the most-advanced pump of its kind.

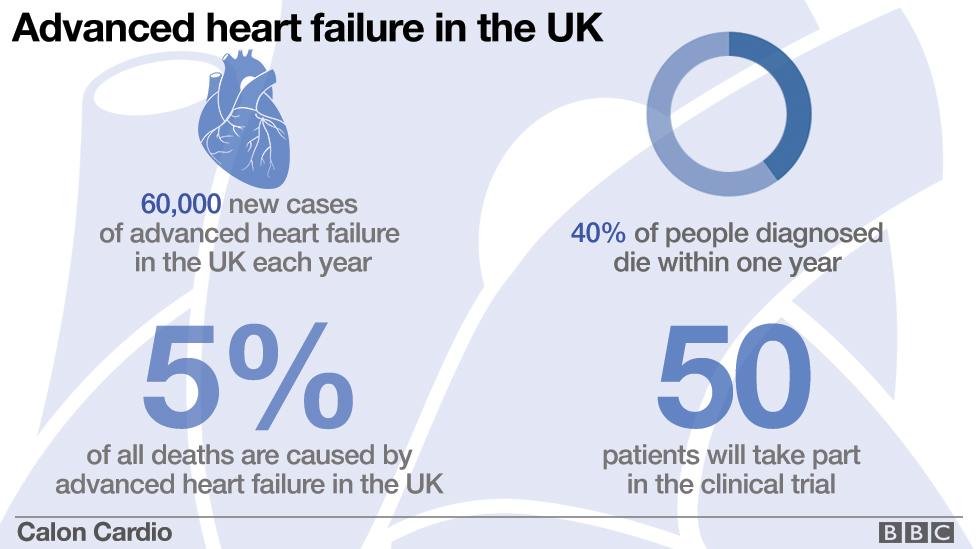

"This is for a very sick group of people and there are millions of them in the world, and hundreds of thousands in the United Kingdom," he said.

"It is the first British pump to be built for this purpose: to treat blood which is flowing through the pump extremely gently and not to do any damage to the blood.

"There are other pumps that have been built that do cause some damage to the blood and, as a result, patients have adverse events that diminish the impact of the implantation and the treatment.

Calon Cardio boss Stuart McConchie said it was the most advanced pump of its kind

"Reliability of these pumps has been established for several years but blood handling is a problem. If they break up red blood cells or white blood cells or damage proteins then there is a cost of that."

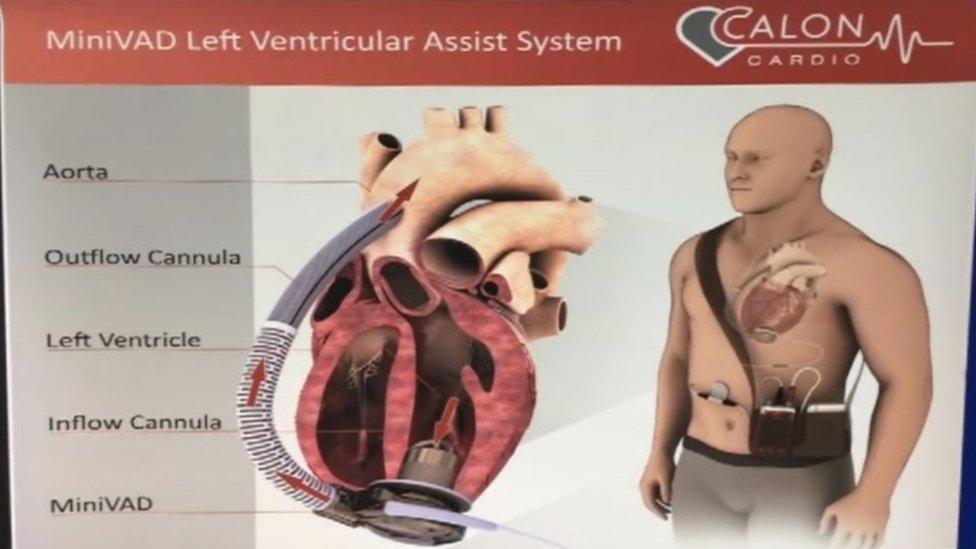

The pump is commonly known as a ventricular assist device (VAD) and the one being developed in Swansea is called a MiniVAD.

After being implanted directly into the heart, it is driven by an embedded electric motor and powered by a battery pack worn by the user.

Diagram of the MiniVAD system which is attached to a battery pack

Mr McConchie said the device was designed to "assist the heart itself and not to replace it".

The last VAD produced was sold to one of the world's major cardiovascular companies for $3.4bn (about £2.6bn), he added.

But while there is a huge monetary value to the product, Mr McConchie said the key aspect is that it will improve a patient's quality of life.

"If we can demonstrate that we have reduced the adverse events, you have something that's much more forgettable that's put inside the body," he added.

"Patients don't have to go back into hospital for correction of any adverse events, so the absolute cost benefit becomes substantial.

"That means the NHS, for example, or a healthcare provider in other countries like the United States, don't have as much cost in treating the patient who has a ventricle assist device and the benefit to society comes with that."

Mr McConchie said the patient experience was "much, much better" if they do not have to visit the hospital frequently.

- Published11 April 2017