Glanrhyd disaster: Memories of train tragedy 30 years on

- Published

Thirty years ago a railway bridge near Llandeilo collapsed, plunging a passenger train into the River Towy and leaving four people dead. Glanrhyd bridge had been partially washed away in the swollen river before the accident, early on Monday 19 October 1987.

Three passengers and three staff escaped but the driver and three passengers drowned. BBC Radio Wales' Gilbert John, who reported from the scene, recalls his memories of the dramatic and tragic disaster.

October 1987 was a month of storms to remember. Mid-month there was the Great Storm, which devastated homes along the south coast of England in particular, with 100mph (160 km/h) winds scything down trees by the thousand.

But the Glanrhyd train disaster in Carmarthenshire, a few days later, was caused by the biblical quantities of rain which fell on south Wales, turning the River Towy into a raging torrent.

That was why, when the 5:27am Heart of Wales line train from Swansea to Shrewsbury set off on the morning of 19 October, there were rail engineers aboard to check the track after reports of flooding and damage.

The first bare details that the Glanrhyd bridge, between Llandeilo and Llandovery, had collapsed and a train had plunged into the river came with the radio headlines later that morning. But those early reports seemed reassuring - no immediate news of casualties.

I had set off from my home below Llandeilo only to be stopped by floodwater across the road north of the town.

As I stood there, a fire engine drove out of the floodwater and stopped with the crew jumping down to check the brakes.

I joined them to get more information and made the innocent comment: "Good news nobody's injured." They turned and sharply told me that four people were trapped in one of the carriages - almost certainly dead.

Flooding in the wake of the Great Storm left the River Towy a "raging torrent"

You have to remember that mobile phones were virtually non-existent in 1987. I ran to a nearby bungalow, hammered on the door and, once I'd explained the circumstances, was given permission by a rather startled housewife to use their phone. That first copy to the BBC newsroom in Cardiff was when the wider world learned the scale of the tragedy.

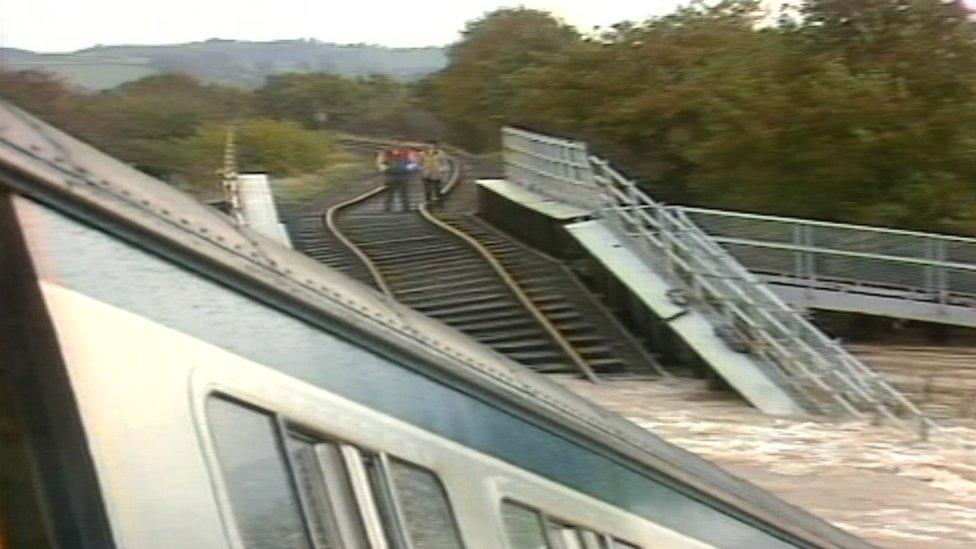

There were rescuers already at the scene; firemen, divers, police officers and others, including rail engineers. All were simply standing, looking at the tail end of the two-carriage train.

One carriage was still mainly on land, the second was twisted at 90 degrees in the river. Nobody could reach it.

The roof was barely above water and the roaring waters of the Towy were battering it and were clearly too ferocious to attempt any rescue.

Six people had escaped the initial plunge into the water. But we knew there were at least four people still in that carriage - the train driver, an elderly couple and a schoolboy, we learned later. But it was certain by that time they were already dead.

Archive footage shows the extent of the disaster

There was a grim frustration for all of us. The carriage was so close. These were trained rescuers desperate to save anyone who might still be alive but it would clearly have been suicide even to attempt it.

The memory alone brings back that sense of wanting to do something - even for me, the least qualified on that twisted rail line.

The days that followed saw more facts emerge and early suggestions of possible causes.

Was floodwater released from the Llyn Brianne reservoir partly responsible for the torrential river flow? That was quickly denied.

Why were there passengers on-board a train being used to survey a possibly dangerous line?

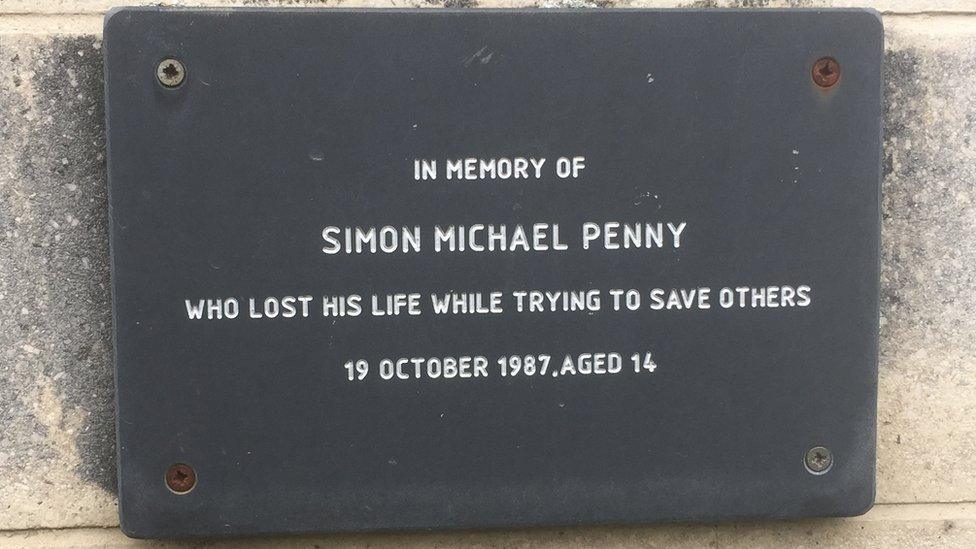

And, inevitably, there was the distraught reactions of relatives. In particular, those of the family of the schoolboy Simon Penny, who had been going back to school. We were told later, he had almost certainly stayed on the train to help others.

Memorial to Simon Penny at Llandovery College

There were the related stories. How Llanelli and Wales rugby star Carwyn Davies, who farmed nearby, had been out early to check his animals in the flooded fields and had seen the collapsed bridge. He had been heading back to raise the alarm when he heard the train coming down the track and plunging into the river.

Then came the questions in the House of Commons and, as time passed, the full inquest into the deaths. The swollen river, it emerged, had scoured beneath the foundations of the bridge, and left it fatally weakened. Ultimately, changes were introduced to prevent such a disaster ever recurring.

Soon after, the Prince of Wales and Princess Diana travelled to Carmarthen to visit the areas hit by the floods, and the name of the latest tragedy - the Glanrhyd Bridge disaster - entered our history books.

- Published9 January 2016