Dangers in the dust: Inside the global asbestos trade

- Published

Canada's Jeffrey mine is looking to boost exports. Photo: Eve Belanger

Banned or restricted in more than 50 countries, white asbestos continues to be widely used in China, India, Russia and Brazil, and many developing countries. The BBC's Steve Bradshaw and Jim Morris from the ICIJ report on an industry supported by a global network of lobby groups.

The Jeffrey asbestos mine in Quebec is an astonishing sight. "Big and beautiful," says one of the regular flow of tourists and locals who peer into its depths from a public observation deck.

Kites glide above the tiny azure pool far below.

Elsewhere in Quebec Province, Janice Tomkins, an amateur watercolourist, is painting birds for the first time. She does not know how many more she will paint because she has mesothelioma - a rare illness linked to asbestos.

Janice believes she is ill because of exposure decades ago to blue and brown asbestos - forms of the mineral now banned.

What is mined in Quebec is a different kind of asbestos - white asbestos or chrysotile - the only kind now used commercially worldwide. Countries like Russia, China, Brazil, and India - although not Canada - use it widely as a cheap and effective building material.

The president of the mine, Bernard Coulombe, told us their chrysotile is "sold exclusively to end-users having the same industrial hygiene practices as Canada," and said the federal and provincial governments have proof this is the case.

But, despite still being mined in Quebec, white asbestos is now banned or restricted in some 52 countries, on the grounds that any form of asbestos can cause devastating illnesses like Janice's.

Opposition

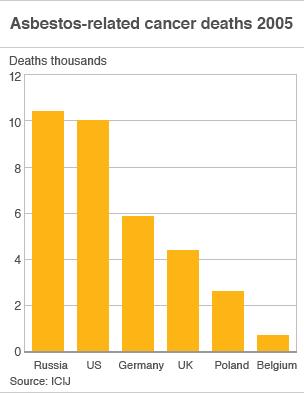

Many scientists fear the continued use of asbestos could significantly prolong a global epidemic of asbestos-related illnesses that began when blue and brown asbestos were legal. The WHO says white asbestos "is a known cause of human cancer," including mesothelioma.

Dr Vincent Cogliano, of the WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer says: "My own personal view is that these risks are extremely high. They are as high as just about any known carcinogen that we have seen, except, perhaps, for tobacco smoke.

"Any exposure is going to prolong the asbestos epidemic - continued export and continued use of chrysotile will increase the incidence of lung cancer and mesothelioma for many decades to come, he said."

White asbestos is flaky and fibrous

Janice does not want the Quebec provincial government to approve a C$58m (US$56m, £37m) loan guarantee that would enable the Jeffrey Mine to boost exports to developing nations such as India.

Defenders of chrysotile insist safe use can prevent any ill effects including cancer - and some argue there's no link to mesothelioma at all.

But there is now a crescendo of opposition to Canadian asbestos exports.

At Janice's hospital in Montreal, Dr Dick Menzies has signed a letter telling the government there is an "overwhelming scientific consensus" that white asbestos use must end.

He is just one of many prominent physicians, academics and others who have besieged the federal and provincial governments with letters of protest.

The WHO says 125 million people encounter white asbestos in the workplace, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 100,000 workers die each year from all asbestos-related diseases.

The president of the mine told us he did not believe these figures were true.

White asbestos is banned in the European Union, with minor exemptions. In the US it is legal but the industry has paid out an estimated $70bn in damages and litigation costs, and asbestos use is limited to automobile and aircraft brakes, gaskets and a few other products.

Backed by a global network of trade groups and scientists, the asbestos industry has depicted the epidemic as a legacy of a darker time, when dust levels were high, blue and brown asbestos were used, and workers had little, if any, protection from the toxic asbestos fibres.

Cheap building materials

"All recent scientific studies show that chrysotile fibres, the only asbestos fibre that is produced and exported from Canada, can be used safely under controlled conditions," said Christian Paradis, environment minister in Canada's conservative government.

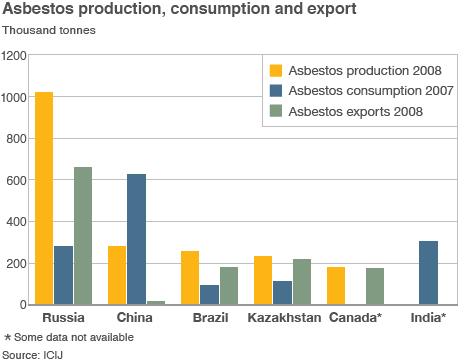

In 2009, Canada sent nearly 153,000 tonnes of chrysotile - or white asbestos - abroad. More than half went to India; the rest went to Indonesia, Thailand, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. At home, it is a different story: Canada used only 6,000 tonnes in 2006, the last year for which data is available.

In the developing world, demand for cheap building materials is brisk. More than two million tonnes of asbestos were mined worldwide in 2009 - much of it to be turned into asbestos cement, which is durable, fireproof and cheap, for corrugated roofing and water pipes. More than half was exported.

Behind the industry's growth in these countries is a marketing campaign involving a diverse set of companies, organised under a dozen trade associations and institutes. This campaign is co-ordinated, in part, by the Chrysotile Institute, a government-backed group in Montreal, which has an office in a smart office block in downtown Montreal.

The BBC did not get past the office block reception desk, but in a telephone interview with ICIJ in February, institute president Clement Godbout insisted: "We never said that chrysotile was not dangerous. We said that chrysotile is a product with potential risk and it has to be controlled. It's not something that you put in your coffee every morning."

The asbestos lobby's influence reaches around the world. Pro-chrysotile groups have spent nearly US$100m since the mid-1980s to support asbestos sales in three countries alone: Canada, India and Brazil.

Critics say the groups' strategy is one borrowed from the tobacco industry: create doubt, contest litigation, and delay regulation. Some industry-funded researchers have published hundreds of scientific papers saying that chrysotile can be used safely. White asbestos, they argue, is significantly less hazardous than brown or blue asbestos, which the industry stopped mining in the 1990s.

Claims made by this small but vocal minority of scientists include that white asbestos fibres:

are rapidly and harmlessly expelled by the lungs

can be safely embedded in cement

have no connection with mesothelioma at all, even if there are possible links to lung cancer

White asbestos is an occupational health issue, they argue, rather than a potential public health disaster. So it is wrong, they say, to deny cheap building materials to developing countries for what are unproven, and at worst highly marginal, health risks.

'Does good job'

Dr John Hoskins, an independent consultant toxicologist specialising in occupational hygiene with particular reference to asbestos, believes ambitious politicians and litigation lawyers are among those orchestrating a campaign against white asbestos that is scaring the public and "committing economic damage".

"You have a cheap product which actually does a good job," says Dr Hoskins, who says he formed his views while working for the UK's Medical Research Council. "I think there's an immeasurably small risk and immeasurably small means it cannot be measured."

But arguments that white asbestos - more than 90% of all asbestos ever mined - can be safely used are disputed by the majority of scientists and public health officials we have spoken to.

The American Public Health Association (APHA) has joined the World Federation of Public Health Organizations (WFPHA), the International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH), and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) in calling for a global asbestos ban.

From China to India, from Mexico to Brazil, compelling recent evidence, and on-the-ground inquiries, indicate how elusive the goal of controlled use can be - whether it is illegal gaskets seized in Brazil, clouds of asbestos dust in Indian workshops, or a Chinese reporter stumbling into a family workshop where workers have inadequate protection.

As for the risk-benefit question, American Barry Castleman, author of Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, has been researching asbestos cement substitutes - roofing and pipes made with cellulose fibres, ductile iron and fibreglass, for example - for the WHO. He says they cost, at most, 10% to 15% more to produce.

Despite the reassuring studies and the million-dollar marketing efforts, the asbestos industry faces stiffening headwinds.

The number of countries imposing bans or restrictions continues to climb, and health and labour activists have sprung up in China, Brazil, India, and other high-use countries. In Brazil, one civil servant said there is now a debate raging inside the federal government about white asbestos - the use of which is permitted in most, but not all, states.

New evidence

And recently, the scientific case against white asbestos may be hardening.

John Hodgson of the UK's Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has estimated the risk of lung cancer from white asbestos is between 10 and 50 times less than from the same exposure to banned blue and brown (amphibole) asbestos.

But he says new evidence from the US had led him to conclude his previous estimates of mesothelioma risk could be higher - "to between a 20th and a 100th" of blue and brown risk.

"I would say that we can't say it's safe," he said, adding that there are very serious levels of uncertainty over these figures - especially at lower exposure levels. The HSE actively supports the EU's white asbestos ban.

Meanwhile, on lung cancer, Alex Burdorf, a public health professor at Rotterdam's Erasmus Medical Centre, said his recent review of earlier epidemiological studies commissioned by the Dutch government, had convinced him that white asbestos was "much more dangerous than previously thought."

"What we have shown is that chrysotile is as dangerous as crocidolite [blue asbestos] for contracting lung cancer, and is also linked to mesothelioma," he said. "I don't think there is safe way of working with asbestos, so I would support a global ban on asbestos purely because of public health risks."

The one thing almost everyone seems to agree on is that little is known about what is actually happening in many countries that still use asbestos.

"Good epidemiology on worker cohorts still using chrysotile could be very helpful," said John Hodgson.

"Whether it's ethical to suggest we should wait and see, rather than working for a ban in those countries one might debate. If countries do decide to continue using chrysotile they should have good systems of monitoring exposure and subsequent illness and mortality, so if they're wrong in their judgement this will emerge as quickly as possible."

In its joint investigation the BBC/ICIJ found little evidence that such comprehensive monitoring is yet widely in place.

Jim Morris, is a staff writer for the ICIJ, specialises in coverage of the environment and public health. Steve Bradshaw is an award-winning documentary film-maker.