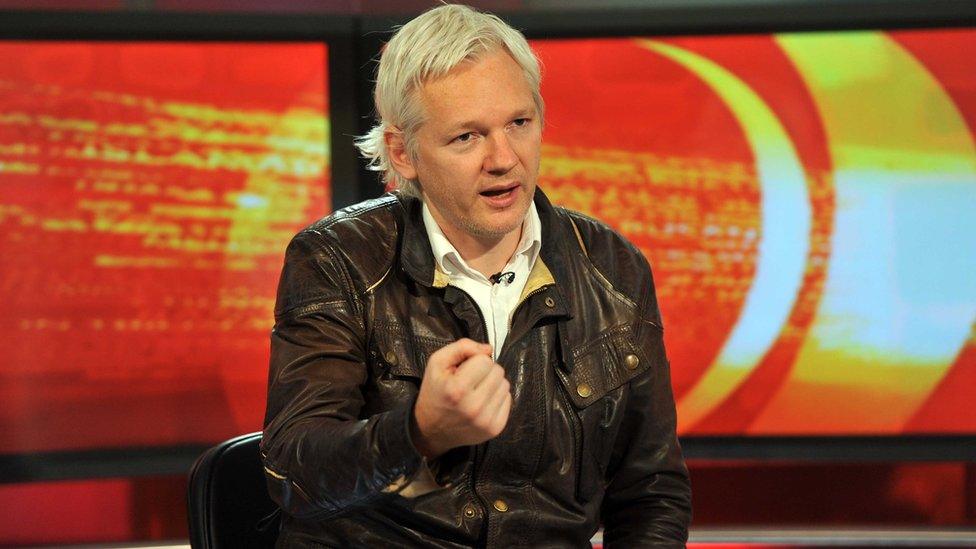

Julian Assange: Campaigner or attention seeker?

- Published

Julian Assange spent years fighting extradition to the US

To his supporters, Julian Assange is a valiant campaigner for truth. To his critics, he is a publicity seeker who has endangered lives by putting a mass of sensitive information into the public domain.

Assange is described by those who have worked with him as intense, driven and highly intelligent, with an exceptional ability to crack computer codes.

He set up Wikileaks, which publishes confidential documents and images, in 2006, making headlines around the world in April 2010 when it released footage showing US soldiers shooting dead 18 civilians from a helicopter in Iraq.

But later that year the Australian was detained in the UK - and later bailed - after Sweden issued an international arrest warrant over allegations of sexual assault.

Assange argued it was a ploy to ultimately extradite to the US to face espionage charges - kicking off a legal saga which has now spanned 14 years, embroiled five countries and reached some of the world's highest courts.

But the 52-year-old is now free - bailed and on his way to the Northern Mariana Islands - where he is on Wednesday expected to plead guilty to a single charge after reaching a deal with US authorities.

He is expected to be released immediately, given the time he has already served in prison in the UK, and will return to Australia.

Hacker beginnings

Assange has been generally reluctant to talk about his background, but media interest since the emergence of Wikileaks has thrown up some insight into his influences.

He was born in Townsville in the Australian state of Queensland in 1971, and led a rootless childhood while his parents ran a touring theatre. He became a father at 18 and custody battles soon followed.

The development of the internet gave him a chance to use his early promise at maths, though this too led to difficulties.

After pleading guilty to "hacking", Assange escaped prison on the condition he did not reoffend

In 1995 Assange was accused, with a friend, of dozens of hacking activities. Though the group of hackers was skilled enough to track detectives tracking them, Assange was eventually caught and pleaded guilty.

He was fined several thousand Australian dollars - only escaping a prison term on the condition that he did not reoffend.

He dabbled in the world of academia - co-writing a bestselling book on the emerging, subversive side of the internet, before studying physics and maths.

Wikileaks work

Assange began Wikileaks in 2006 with a group of like-minded people from across the web, creating a web-based "dead-letterbox" for would-be leakers.

"[To] keep our sources safe, we have had to spread assets, encrypt everything, and move telecommunications and people around the world to activate protective laws in different national jurisdictions," he told the BBC in 2011.

"We've become good at it, and never lost a case, or a source, but we can't expect everyone to go through the extraordinary efforts that we do."

Assange told the BBC that in order to protect sources he would "encrypt everything"

Adopting a nomadic lifestyle, he ran Wikileaks from temporary, shifting locations.

He could go for long stretches without eating and focus on work with very little sleep, according to Raffi Khatchadourian, a reporter for the New Yorker magazine who spent several weeks travelling with him.

"He creates this atmosphere around him where the people who are close to him want to care for him, to help keep him going. I would say that probably has something to do with his charisma."

But it was in 2010 that Wikileaks - and Assange - really shot to prominence, with the release of the footage of the US helicopter firing on civilians in Iraq.

He promoted and defended the video, as well as the massive release of classified US military documents on the Afghan and Iraq wars in July and October 2010.

The whistleblowing website went on to release new tranches of documents, including five million confidential emails from US-based intelligence company Stratfor.

It soon found itself fighting for survival, when a number of US financial institutions began to block donations.

And shortly after, Swedish authorities began chasing him for questioning over claims that he had raped one woman and sexually molested and coerced another in August 2010, while on a visit to Stockholm to give a lecture.

By the end of 2010, an international warrant had been issued for his arrest.

Ecuador offers asylum

From the embassy's balcony in 2012, Assange urged the US to end its "witchhunt" against Wikileaks

Assange says the encounters were entirely consensual - and the rape allegations were part of a politically motivated smear campaign - spending a year and a half challenging the warrant in court.

When the UK Supreme Court upheld it, Assange turned to then Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa for help, the two men having expressed similar views on freedom in the past.

In June 2012 he sought asylum in the Ecuadorean embassy in London to avoid extradition.

His stay at the embassy was punctuated by occasional press statements and interviews. He made a submission to the UK's Leveson Inquiry into press standards, saying he had faced "widespread inaccurate and negative media coverage".

It was during this time that concerns over his health first began to surface - but Assange dismissed reports that he would be leaving the embassy to seek medical treatment.

Assange dismissed reports in 2014 that he would be leaving the embassy to seek medical treatment

After spending almost seven years inside the embassy, Assange was dramatically dragged from the premises and arrested by British police on 11 April 2019.

Ecuadorean President Lenín Moreno - who said he had "inherited" the situation from his predecessor - tweeted that his country had taken "a sovereign decision", to withdraw his asylum status.

Mr Moreno and his government had grown increasingly frustrated with Assange and his refusal to follow the rules they had imposed for his continued stay in the embassy.

There were "repeated violations to international conventions and daily-life protocols" by Assange, he said in a video statement.

But Ecuador had requested that Great Britain guarantee that Assange would not be extradited to a country where he could face torture or the death penalty, Mr Moreno added.

Legal saga drags on

In 2019 Met Police officers dragged Assange out of the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he had stayed since 2012

Assange was taken into custody at a central London police station - charged with failing to surrender to court back in 2012 - and on 1 May 2019 was sentenced to 50 weeks in jail.

In the following weeks, Swedish prosecutors promptly reopened their investigation into the 2010 rape claims and the US publicly charged Assange with violating the Espionage Act, related to the publication of classified documents in 2010.

The US Department of Justice has described the leaks as "one of the largest compromises of classified information in the history of the United States".

Wikileaks said the announcement was "madness" and "the end of national security journalism".

As Assange prepared to fight against extradition to the US, Swedish prosecutors announced that the investigation into the 2010 rape allegation had been dropped, because the evidence against Assange was "not strong enough to form the basis for filing an indictment".

Since then his case has been tied up in legal back-and-forth and a series of appeals.

In 2021, a British court ruled in his favour, blocking his extradition - but that was later successfully appealed by the US government.

And just last month the UK Supreme Court decided that Assange could appeal the US extradition order - again.

All the while, Assange has sat in London's maximum security Belmarsh Prison.

It was there that in 2022 he married his partner of seven years, Stella Moris, a South African lawyer and long-time member of his legal team. She is also the mother of Assange's two young children, who were conceived while Assange was living in the Ecuadorean embassy.

Julian Assange’s wife said she dreaded going public with their relationship

His family have long said his health was steadily and dramatically declining and they feared he would die or kill himself.

As the saga has dragged on, the UK and the US have faced growing pressure - from public campaign and from Assange's home country of Australia - to resolve the case.

In February Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the country as a whole shared the view that "enough is enough".

"This thing cannot just go on and on and on indefinitely".

Rights groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have all called for his release, saying his treatment has been cruel and his case a threat to press freedom.

He's also won support from countless figures of global power and influence, including former leader of the UK Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn, linguist Noam Chomsky, Baywatch star Pamela Anderson, and the late fashion icon Dame Vivienne Westwood.

The late Dame Vivienne Westwood had appeared at rallies calling for Assange's release

But his critics - which include former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and retiring Republican stalwart Mitch McConnell- say he is not a journalist and endangers lives by publishing troves of documents without redaction.

After the final hearing on Wednesday in the US territory of Saipan - a Pacific island north of Guam - he is expected to return to Australia and be reunited with his family.

They have expressed relief and thanked his supporters.

"I am grateful that my son's ordeal is finally coming to an end. This shows the importance and power of quiet diplomacy," his mother Christine Assange said in a statement.

- Published26 June 2024

- Published12 April 2019