How do you define genocide?

- Published

Some have argued that the only genocide was the Nazi Holocaust

Genocide is understood by most to be the gravest crime against humanity.

It is defined as a mass extermination of a particular group of people - exemplified by the efforts of the Nazis to eradicate the Jewish population in the 1940s.

But behind that simple definition is a complicated tangle of legal concepts concerning what constitutes genocide and when the term can be applied.

Definition and debate

The term genocide was coined in 1943 by the Jewish-Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who combined the Greek word "genos" (race or tribe) with the Latin word "cide" (to kill).

After witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust, in which every member of his family except his brother was killed, Dr Lemkin campaigned to have genocide recognised as a crime under international law.

His efforts gave way to the adoption of the United Nations Genocide Convention, external in December 1948, which came into effect in January 1951.

Article Two of the convention defines genocide as "any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such":

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

The convention also imposes a general duty on states that are signatories to "prevent and to punish" genocide.

Since its adoption, the UN treaty has come under criticism from different sides, mostly by people frustrated with the difficulty of applying it to specific cases. Some have argued that the definition is too narrow; others that it is devalued by overuse.

Ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutus were targeted in the Rwandan genocide

Some analysts say the definition of genocide is so narrow that none of the mass killings perpetrated since the treaty's adoption would fall under it.

The objections most frequently raised against the treaty include:

The convention excludes targeted political and social groups

The definition is limited to direct acts against people, and excludes acts against the environment which sustains them or their cultural distinctiveness

Proving intention beyond reasonable doubt is extremely difficult

UN member states are hesitant to single out other members or intervene, as was the case in Rwanda

There is no body of international law to clarify the parameters of the convention (though this is changing as UN war crimes tribunals issue indictments)

The difficulty of defining or measuring "in part", and establishing how many deaths equal genocide

But in spite of these criticisms, there are many who say genocide is recognisable.

In his book Rwanda and Genocide in the 20th Century, the former secretary-general of Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), Alain Destexhe, wrote: "Genocide is distinguishable from all other crimes by the motivation behind it.

"Genocide is a crime on a different scale to all other crimes against humanity and implies an intention to completely exterminate the chosen group. Genocide is therefore both the gravest and greatest of the crimes against humanity."

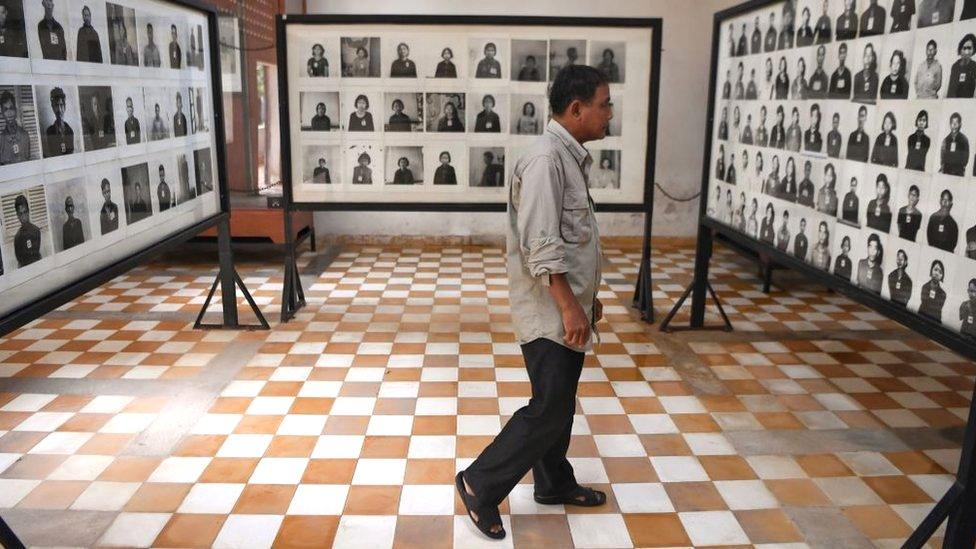

A man looks at photographs of Khmer Rouge victims at the Tuol Sleng genocide museum in Phnom Penh

Mr Destexhe has voiced concern that the term genocide has fallen victim to "a sort of verbal inflation, in much the same way as happened with the word fascist", becoming "dangerously commonplace".

Michael Ignatieff, former director of the Carr Centre for Human Rights Policy at Harvard University, has agreed, arguing that the term has come to be used as a "validation of every kind of victimhood".

"Slavery, for example, is called genocide when - whatever it was, and it was an infamy - it was a system to exploit, rather than to exterminate the living," Mr Ignatieff said in a lecture.

The differences over how genocide should be defined have also led to disagreements on how many genocides occurred during the 20th Century.

How many genocides have there been?

Some say there was only one genocide in the last century: the Holocaust.

Others say there have been at least three genocides as defined by the terms of the 1948 UN convention:

The mass killing of Armenians by Ottoman Turks between 1915-1920, an accusation that the Turks deny

The Holocaust, during which more than six million Jews were killed

Rwanda, where an estimated 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus died in the 1994 genocide

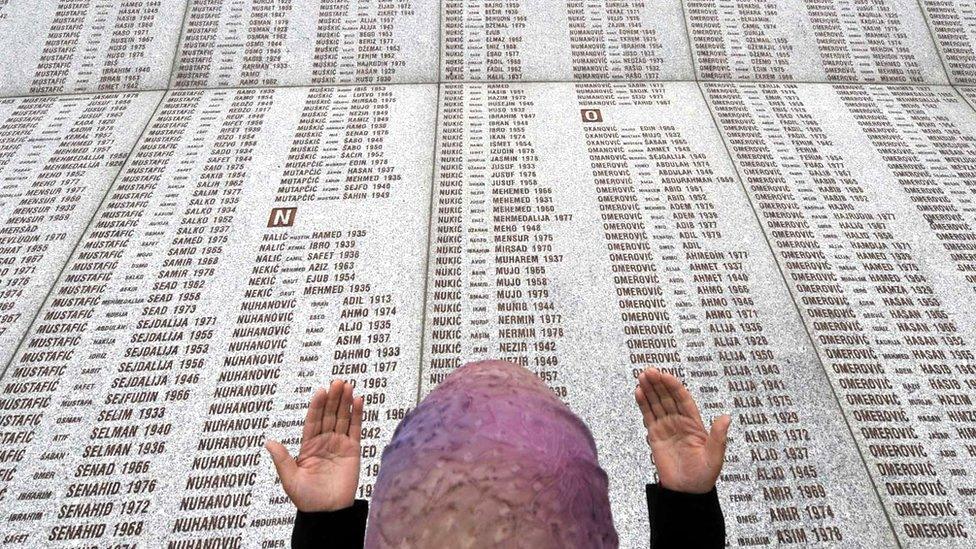

And in recent years, other cases have been added to the list by some. In Bosnia, the 1995 massacre at Srebrenica has been ruled to be genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

Other cases include the Soviet man-made famine of Ukraine (1932-33), the Indonesian invasion of East Timor (1975), and the Khmer Rouge killings in Cambodia in the 1970s, during which an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians died by execution, starvation, or forced labour.

There is disagreement over the fact that many of the victims of the Khmer Rouge were targeted because of their political or social status - putting them outside of the UN definition of genocide.

The International Criminal Court in 2010 issued an arrest warrant for the President of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, on genocide charges, accusing him of waging a campaign against the citizens of the Sudanese region of Darfur where about 300,000 people are said to have died and millions more displaced during seven years of fighting.

More than 7,000 Muslim men were killed at Srebrenica in 1995

More recently, in March 2016, the US accused the jihadist group Islamic State (IS) of carrying out genocide against Christian, Yazidi and Shia minorities in Iraq and Syria.

IS was "genocidal by self-proclamation, by ideology and by actions, in what it says, what it believes and what it does," then-Secretary of State John Kerry said.

In 2017, The Gambia submitted a case to the International Court of Justice accusing Myanmar of carrying out a genocide against the Rohingya people, alleging "widespread and systematic clearance operations" in Rohingya villages.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people have fled Myanmar into bordering Bangladesh and elsewhere, and thousands are reported to have been killed.

In 2021, the US, Canadian and Dutch governments all formerly accused China of committing a genocide against the Uighur people in Xinjiang, while several other countries brought parliamentary resolutions making the same accusation.

Evidence suggests China has subjected the Uighurs to forced sterilisation, forced labour, mass detention, and systematic rape and torture - actions which many say meet the criteria of a genocide. China denies the charges.

A former inmate describes conditions at a secret Chinese camp for Uighurs

Genocide prosecutions in history

The first case to put into practice the convention on genocide was that of Jean Paul Akayesu, the Hutu mayor of the Rwandan town of Taba at the time of the killings. In a landmark ruling, a special international tribunal convicted Akayesu of genocide and crimes against humanity on 2 September 1998.

More than 85 people were subsequently convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, 29 on counts of genocide.

In August 2010, a leaked UN report alleged that Rwandan Hutus, perpetrators of the 1994 genocide, may themselves have been victims of the same crime.

In 2001, Gen Radislav Krstic, a former Bosnian Serb general, became the first person to be convicted of genocide at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

Krstic appealed against his conviction, arguing that the 8,000 people killed constituted "too insignificant" a number to be a genocide. In 2004 the ICTY rejected his appeal.

In 2007, the former Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladić, nicknamed the "butcher of Bosnia", was sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

And in 2018, Nuon Chea, 92, and Khieu Samphan, 87, were both sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide and crimes against humanity for their roles in the Khmer Rouge killings.

- Published8 February 2021

- Published27 August 2010