Would more holiday be good for America?

- Published

In theory, the summer is over here. We've just had August Bank Holiday, the British equivalent of Labor Day, the last official three-day weekend of the summer.

Guaranteed paid vacations don't take a lot of getting used to - even if the weather is variable

But the little development of flats I live in is still quiet. A majority of folks still seem to be on vacation.

Not me, of course. I may have lived in Britain for 25 years but I'm an American by birth, self-employed, and so after nine days away, I'm back in harness, ready for action.

And as most of my work this week involves organising a lecture tour in the US in the autumn, I am having a productive time. It may be the last week of summer in the land of my birth but almost everybody I need to be in touch with in America is at their desk sounding harassed as ever.

Month-long shutdown

When people speak of the Anglo-Saxon model of capitalism, what they are usually referring to is the remarkable Anglo-American coincidence that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan came to office at the same time and shared identical economic philosophies and policy gurus.

Those days are gone and the Anglo-Saxon model is more nostalgia than reality. But even in the headiest days of the Iron Lady and the Gipper, one place where the model didn't hold was on the issue of paid annual leave.

British workers get generous guarantees of time off, currently 20 days a year. That is one full month of paid leave. Judiciously planned around public holidays - eight in England and Wales, nine in Scotland and 10 in Northern Ireland - it means this country basically shuts down for most of August and between Christmas and New Year.

It's not just Britain where good vacation is the norm.

The figures in a 2007 report from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), external are stark. It looked at 21 of the richest countries in the world, and found that only one, the US, does not impose a legal mandate on employers to provide time off.

Come summer, lucky Americans may get one week of vacation

Obviously, people in America do get paid annual leave, but for most wage earners it is subject to so many different calculations based on seniority and how much you earn, it can only be described as miserly.

In other words, it is a privilege to be earned rather than a normal part of compensation.

Nine days of annual leave is what the average American accrues during the course of a year. So you have to be at your job for 12 months before you begin to get even that amount.

If you figure that folks might take a day or two at Christmas, maybe Thanksgiving, and keep a day or two in the bank for a family emergency, what you're left with come the good weather is a week of vacation if you're lucky.

Raw fear

The difference between American attitudes to vacation and those of Britons and others is hard to explain.

I have worked for wages on both sides of the Atlantic and the experience is broadly comparable. Yet no British worker - nor most British employers - would accept such little vacation entitlement.

Holidays as part of compensation are one of the small, subtle things that keep a workplace happy. Happy workers are productive workers in ways that can't be measured statistically.

Whenever citing Americans' acceptance of the longer hours they work or their lack of paid leave, the cliche is to say it goes back to the country's Puritan heritage or the Protestant work ethic.

I disagree. I think it comes from raw fear.

Most Americans are not descended from Puritan stock. The people I have worked with in a variety of jobs - I wasn't always a journalist - would have liked nothing more than a guarantee of 20 days of paid holiday a year.

But since the heyday of Thatcher and Reagan, they have been increasingly afraid to ask for it directly and way too afraid to come together and demand it as a group.

It is easy enough to get fired in the US, and when people have a job they tend not to want to make waves.

Social benefit

It's a shame really. In a country where economic insecurity is resulting in a disturbingly aggressive public debate - disturbing, at least, to one American expat - it would probably be a good thing for employers to start paying their workers to take extra chill time.

The benefit to society would be immediate because the thing is, guaranteed paid vacations don't take a lot of getting used to.

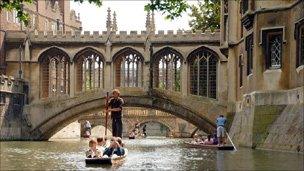

Cambridge (UK): Fine in summer, but miserably damp and cold the rest of the time

For all their pride in working longer hours with no vacation than anyone else, I think Americans could adjust very quickly to having paid down time.

Take the case of a colleague who worked for the International Herald Tribune in Paris. The Trib is owned by The New York Times and like most of its minuscule staff, he was on assignment from New York.

We met for lunch while I was in Paris researching a book a couple of years ago, and as we ate he told me he was taking the following week off. It was March, not vacation season, and I asked him why he was taking it then.

He told me he worked under French employment rules and was legally obliged to take his vacation allocation. He said he couldn't use it all up in the summer, as there were too many weeks he had to take.

So he was grabbing some time out of season in England, in Cambridge. American readers won't know what the weather in that ancient university town is like in late winter, but he was not going to have to pack shorts.

Still he cackled with glee as he bragged on this situation. He seemed so relaxed and happy I let him pick up the tab for lunch.

Anyway, things aren't likely to be getting better in the US.

The CEPR statistics I mentioned above date back a few years. In the current economic climate, where people are losing their jobs in droves, if they are lucky enough to find new employment they will go to the bottom of the seniority list and have to accrue vacation days from the beginning.

My guess is that the next such analysis will show Americans having less paid holiday than ever.

Michael Goldfarb, external is a journalist and broadcaster who has lived in London since 1985. Formerly with National Public Radio, he is now the London correspondent of globalpost.com, external.

- Published20 July 2010

- Published5 August 2010