Uneven progress of UN Millennium Development Goals

- Published

The target for reducing poverty is likely to be met, but not all will benefit

World leaders are descending on the UN headquarters in New York for a display of commitment to reduce sharply global poverty and hunger. The summit aims to take stock of progress on eight UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted 10 years ago, and redouble efforts to meet them by 2015. BBC UN correspondent Barbara Plett looks at the issues officials will face.

The United Nations is billing this as a high-stakes event.

"The path that will be set at the summit will determine the direction and results, success or failure, of the entire MDG venture," says Olav Kjorven, a senior official in the UN's main development agency, the UNDP.

"With five years to go, it's a moment of truth for the whole international community."

The truth is that poverty has fallen, but progress has been uneven, and most of the goals are off-target to meet the deadline.

One of them - halving world poverty - is likely to be met, largely because of robust economic growth in China and India.

But less has been achieved on others, such as decreasing hunger, improving access to health and education, and helping mothers and children.

Success stories

Many countries do have success stories to tell.

African farmers, for instance, have seen enormous benefits from seed and fertiliser subsidies. Such interventions turned Malawi from staving off famine in 2005 to harvesting crop surpluses.

There are also plenty of failures.

World hunger is on the rise since the adoption of the UN goals, with nearly a billion people suffering.

And the number of women who die in childbirth every year is still in the hundreds of thousands, falling far short of the UN goal to cut maternal deaths by three quarters.

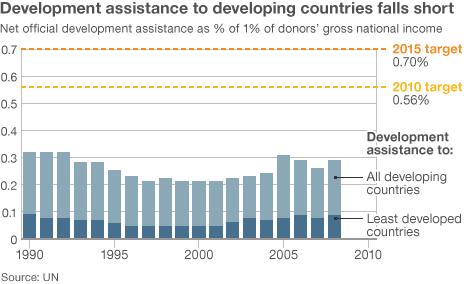

One reason for failure is that, although the amount of development assistance has increased over the past decade, the richest states have failed to meet their commitment to donate 0.7% of gross national income.

Of the so-called G-8 countries, the United Kingdom gives the highest level of aid at 0.51% and Italy the lowest at 0.15%. The US is not far behind at 0.20%, although given the size of its economy, it supplies the highest volume of development assistance.

G8 countries also failed to meet a promise to double aid to Africa by 2010, made at a summit in Gleneagles, in Scotland, five years ago.

They maintain that it is due to the global financial crisis.

But there was a shortfall well before the crash, says Jeffrey Sachs, an MDG adviser to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

"One could say there was a certain lack of seriousness in this process from the start," he says.

"In 2007 and 2008 I would say [to G8 officials], what about Gleneagles? You have a commitment, 2010 is very explicit. And very senior officials in the German government would say to me, 'Oh Professor Sachs, you don't think they're going to be honoured, do you?'"

Practical steps

Prof Sachs also argues that the aid which is given could be used much more effectively.

Rich countries tend to focus on their own projects rather than pool their money into global funds that support programmes designed by developing nations - a model that has proven successful, he says.

Donor nations counter that developing states are not always effective partners, because of corruption and poor governance. And the UN is urging governments in the developing world to improve tax collection, as well as make sure that economic growth benefits the very poor.

Another reason for failure is the inferior position of women and girls in many poor nations, due to entrenched inequalities. Aid workers say rectifying this is crucial, because the status of women has a huge impact on MDGs related to children, health and education.

Given these systemic problems, some activists want the summit to frame the UN goals not as mere aspirations but as human rights anchored by legislation, as a way of holding governments to account.

And, alongside calls for greater commitment to meet aid pledges, some also want a greater emphasis on what they say are structural causes of global poverty: the burden of foreign debt in the developing world, and trade regimes that do not allow poor countries to develop their economies in ways that would best meet the needs of their people.

"The MDGs have been useful in mobilising money and energy," says Olivier De Schutter, the UN's Special Rapporteur on the right to food. "But they attack the symptoms of poverty - underweight children, maternal mortality, HIV prevalence - while remaining silent on the deeper causes of underdevelopment and hunger.

"Statistics are not a substitute for politics."

The summit is expected to declare that achieving the Millennium Development Goals is do-able by 2015, with the right combination of money, policies and, above all, political will.

But there is scepticism, and critics will be looking out for mention of specific steps and practical action plans to flesh out the rhetoric.