Nuclear power at heart of Russia's Arctic ambition

- Published

Richard Galpin gets rare access to Russia's floating nuclear power station

Could the Arctic become a battleground over control of large reserves of oil and gas thought to lie under the Arctic Sea, or will there be co-operation in the polar region? This will be a question for politicians and experts from around the world as they meet in Moscow.

In a grimy shipyard in St Petersburg, an ugly hulk of red-painted metal sits floating in the dock.

On deck, workmen scurry back and forth, hammering, drilling and welding.

In 2007, Artur Chilingarov planted a Russian flag on the Arctic seabed

This strange construction, part ship, part platform, is unique and lies at the heart of Russia's grand ambitions for the Arctic.

When it is completed in 2012, it will be the first of eight floating nuclear power stations which the government wants to place along Russia's north coast, well within the Arctic Circle.

The idea is the nuclear reactors will provide the power for Russia's planned push to the North Pole.

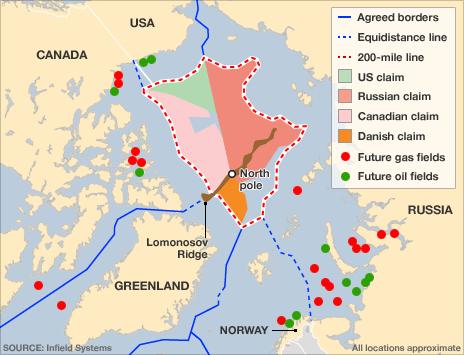

Moscow is claiming more than a million square kilometres of extra territory in the Arctic, stretching from its current border in the Arctic Sea, all the way to the Pole.

'Complicated and dangerous'

The territory includes an underwater mountain range called the Lomonosov ridge, a area which some Russian scientists claim could hold 75 billion barrels of oil.

This is more than the country's current proven reserves.

"These [floating nuclear power stations] have very good potential, creating the conditions for exploring the Arctic shelf and setting up drilling platforms to extract oil and gas," says Sergey Zavyalov, deputy director of the operating company, Rosenergoatom.

"Work in the Arctic is very complicated and dangerous and we should ensure there's a reliable energy supply."

He says each power station, costing $400m, can supply electricity and heating for communities of up to 45,000 people and can stay on location for 12 years before needing to be serviced back in St Petersburg.

And while initially they will be positioned next to Arctic bases along the North coast, there are plans for floating nuclear power stations to be taken out to sea near large gas rigs.

"We can guarantee the safety of our units one hundred per cent, all risks are absolutely ruled out," says Mr Zavyalov.

But many environmentalists are alarmed and warn of the consequences of a nuclear accident in the pristine and fragile Arctic environment.

As Russia builds the infrastructure needed to operate in the Arctic, its Polar explorers announced this week they were stepping up efforts to provide the scientific evidence needed to convince the United Nations that Russia's claim to the Lomonosov ridge is valid.

Artur Chilingarov, who three years ago used a mini-submarine to plant the Russian flag on the seabed under the North Pole, will lead another expedition next month which will launch a drifting research station in the region.

Russia needs to collect soil samples from the seabed to prove the Lomonosov ridge is part of the Russian landmass.

The government wants this research completed as quickly as possible because it's declared that the Arctic should be Russia's main source of oil and gas by 2020

And also because Canada is making a rival claim to the territory.

Compromise sought

But Russian scientists believe it could take another 10 years before enough evidence is collected and already tensions with Canada are rising.

"Russia does not want conflict with the other countries surrounding the Arctic," says Vladimir Kotlyakov, honourary president of the Russian Geographical Society and an Arctic expert.

"But naturally nobody wants to give up their territory.

"So we will make a huge effort to hang on to the territory which we think belongs to Russia."

"Of course conflict is always possible, but I repeat that the politicians currently in power in Russia want compromise."

They may want compromise, but they are pursuing a dual-track policy, pushing forward on every front to ensure Russia is the dominant power in the region even before the UN makes a ruling on the territorial disputes.

Although Moscow denies it's setting up special military forces or bases to protect its interests in the Arctic, it is establishing a new coastguard under the control of the all-powerful intelligence agency, the FSB.

Richard Galpin gets on board an ice-breaking ship that would make it much easier for Russia to send oil and gas exports to Asia

Quick route to Asia

And this summer a Russian oil-tanker made a record-breaking voyage through the Northeast passage, which runs along Russia's northern coast linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

The state-owned tanker carrying 70,000 tonnes of oil destined for China, was the largest to sail through the passage from Murmansk to the Bering Strait, completing the journey in less than two weeks.

All this is made possible by the melting of the Arctic ice in the summer months.

The route along the Northeast passage from Russia to Asia which is now opening up, is many days quicker than the traditional route via Europe, the Suez Canal and around India.

Although the ships still need to be escorted by ice-breakers, it is a tantalising opportunity for Russia which wants to sell more oil and gas to energy-hungry countries like China.

With some scientists predicting that there may be no ice at all in the summer by 2030, Russian officials are confident the Northeast passage will become a major route for energy supplies to Asia.

"We believe that five or six months a year are now available [for sailing through the Northeast passage]," says Sergei Frank, the chief executive of the state-owned shipping company, Sovcomflot, whose tanker made the record-breaking voyage.

"And if we can build stronger and smarter ships and find the best routes, then we can enlarge this window a bit."

Next year Mr Frank is planning to send even bigger tankers through the passage.

And on the broader issue of who the Arctic belongs to, he has no doubt that Russia is the rightful owner.

"Your very famous prime minister Winston Churchill, had a very proper saying: Right or wrong, but it's my country.

"The first serious Russian expedition in this area was launched in the 16th Century.

"This is our home."

- Published21 September 2010

- Published9 July 2010

- Published15 September 2010

- Published2 August 2010