Mid-life crisis for Amnesty?

- Published

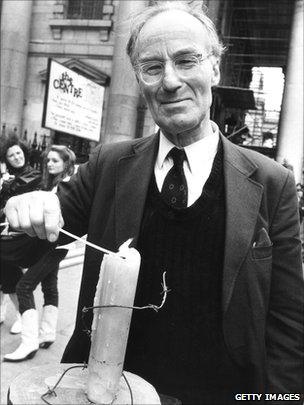

Peter Benenson's letter writing to dictators formed the foundations of Amnesty

To understand Amnesty International at all, you need to think of this: an ordinary citizen sits in an ordinary home, writing an extraordinary letter on behalf of somebody they don't know, to a dictator who doesn't care.

The letter says: "We know you have imprisoned X. We know they are illegally detained. Be warned. We will go on writing until you have freed them."

The absurd act of faith that writing letters about prisoners of conscience might have an effect on the most hardened of dictators was first made by one man 50 years ago - the British lawyer, Peter Benenson.

He was so incensed at the imprisonment of two Portuguese students for a trivial insult to a dictator, that it stirred him to set up an international campaign on behalf of all political prisoners.

Incredibly, it caught on.

Political prisoners, prisoners of conscience, were acutely of their time in the 1960s, in a world thick with dictatorship and totalitarianism - fascist dictatorships in Spain, Portugal and much of Latin America, despots aplenty in Africa, communism from East Germany through the Soviet Union to China. The letters started to flow in all directions, as well as the evidence of their impact.

Prisoners released

Within three years of its foundation, Amnesty members had "adopted" 770 prisoners and no fewer than 140 were released.

By 1970, Amnesty could claim 2,000 prisoners released, membership in the tens of thousands and acceptance by the international community.

It was Amnesty's three-year campaign against torture that led to the unanimous UN adoption of the Declaration against Torture in 1975.

And the awards kept pouring in, such as the Nobel Peace Prize in 1977. As Amnesty's profile grew, so did its ambitions.

In 1985, it took on the plight of refugees, in 1989 the death penalty. By 1996 Amnesty was campaigning for a permanent International Criminal Court.

Amnesty's own rhetoric grew - by 2001 it spoke of pursuing the "full spectrum of human rights", including economic, social and cultural rights. By 2009, it decided to campaign against "poverty, insecurity and exclusion".

But Amnesty's very success has brought problems with it that surround the organisation on its 50th anniversary.

Mission creep?

To campaign for prisoners of conscience is one thing, very tangible. To enlarge the campaign to concern itself with "prisoners of poverty" makes it so large and all-embracing as to be virtually meaningless.

Has it become a body more concerned with feeling good rather than doing good? Has it fallen foul of "mission creep"?

The broader remit is both a good and a bad thing, according to documentary film maker, Roger Graef, whose promotional fundraising work helped make Amnesty a household name.

He welcomes Amnesty's involvement in more causes but also has worries.

"I don't think the image you convey with the brand of Amnesty is anything like as clear as it was for the people who are behind bars for speaking out against oppression.

"The proposition was so clear and irresistible for anybody who had a conscience that even the dictators were moved by the letters."

The controversies have multiplied in recent years, particularly the way it campaigned against Guantanamo Bay, highlighting the rendition of detainees and their treatment in Guantanamo Bay.

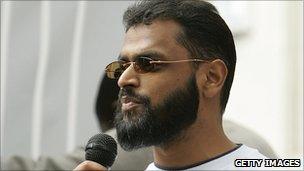

When Amnesty UK began using the released Guantanamo detainee, Moazzam Begg as more than a victim of ill treatment, rather a representative of human rights, it provoked a full-scale row.

Gita Saghal, Amnesty's long standing head of gender, protested publicly and left the organisation.

Amnesty UK faced criticism over its relationship with Guantanamo detainee Moazzam Begg

She charged that Amnesty was soft towards non-state organisations, however violent they might be; and that with Moazzam Begg, it failed to follow its own advice on "making the distinction between supporting what he went through in Guantanamo and treating him as a human rights advocate".

More problematically, in a letter responding to supporters of Ms Saghal, Amnesty UK used the phrase "defensive jihad" as if the organisation itself condoned any violence that might be committed under its terms. Even supporters of Amnesty think the phrase was incautiously used.

Throughout this time, Amnesty UK has played a straight bat, explaining that a full internal inquiry revealed nothing that required significant change in the way it behaved or presented itself.

"Amnesty has been a tremendous defender of victims of state abuses where there have been few such about," says human rights lawyer, Conor Gearty. He argues that is what Amnesty should do because that is where it is most needed. Other bodies will inevitably come under scrutiny

"What is very dangerous," he says, "is if Amnesty or any other human rights organisation allows itself to be persuaded that it needs to police the actions of third parties on an equal level."

Secular church

Striking the balance sheet on Amnesty at 50 is a complex activity.

Its new Secretary General, Shalil Shetty, finds a big agenda awaiting his attention.

It is still largely a Northern, white-liberal body with its roots in Christianity, Judaism, and Quakerism. Its members are mostly in Britain, the United States and Holland.

It is rather like a secular church, though many would feel uncomfortable with such a thought. Even its friends say it is a bit colonial too. Can it be truly internationalised?

More simply, is Amnesty trying to do too much? Is it now simply: too much about everything?

Does it need to reconnect to the original single simple improbable vision of its founder Peter Benenson?

Fifty years ago he believed that ordinary people could do good by personal acts of faith, by bearing witness through an act of conscience; he believed that if you wrote your letter someone else might be set free?

The idea still retains its original power.

Amnesty at 50 can be heard on BBC Radio 4 at 8pm on Tuesday 28 December 2010 and after on BBC iPlayer

- Published11 December 2010

- Published7 December 2010