One year on, Haiti still in ruins

- Published

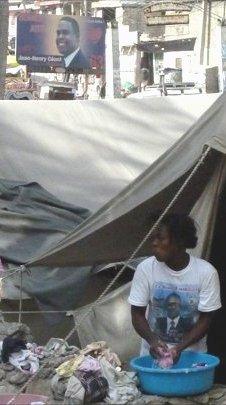

About 180,000 homes in Haiti were completely destroyed by the earthquake

One year on from the earthquake that devastated Haiti, the massive aid effort has yet to bring stability to the country as cholera, rape and despair take hold.

Some $11bn (£7bn) worth of aid has been pledged to the country over the next 10 years, but much of that money has yet to arrive following concerns about government corruption and ongoing riots after November's disputed election.

In the centre of Port-au-Prince, the presidential palace still lies in ruins.

What was a large, green open space just beyond the palace grounds is nothing but a sea of tents.

After all this time, the piles of rocks, wood and mangled metal that were once homes and offices still line the streets.

Mountains of it fester between the homes that were spared, like rotten teeth.

For many, the blame lies firmly at the door of the estimated 4,000 international aid agencies operating in the country.

Some argue aid agencies are giving incentive to people staying in camps

"Nobody knows what they are doing, nobody knows who is sending here, nobody knows how much money they have, nobody knows in what field they are intervening," says Haitian sociologist and university lecturer Daniel Supplice.

"They are all over the place."

He also blames the Haitian government for doing little or nothing to speed Haiti's recovery, but his special ire is reserved for the 12,000 UN peace keeping - or stabilisation - troops, which cost more than $600m a year.

"They are here for security, as you know - no security. Things have never been worse than they are right now," he says.

"They are here to rebuild - as you see, nothing has been rebuilt. The worst thing is, they have destroyed the state. It is an occupation."

As you walk down streets in the capital, splashes of colour are daubed on many of the homes you pass.

Green means the house is fit to live in, yellow means it needs repairs, and red means it is only fit to be demolished.

The trouble is, there is little sign of repairs or demolitions. Few people are returning to the homes that are fit to live in.

Efforts to remove rubble have been painfully slow

Many are too scared to go back, and others simply cannot afford to - including presidential adviser Jean Renald Clerisme, who has one of Haiti's best paid jobs.

"I am in a rented house. And I am planning to move, and they are asking me $2,000 for rent. It is more than half of my salary," he says.

"When you have foreigners, the price goes up and the local cannot afford to pay."

In addition to pushing up local house prices, he says, foreign aid workers are actually encouraging more people to live in camps by concentrating nearly all their services around them.

Anger is never far from the surface in the huge camp in the formerly middle-class area of Petionville, a former golf course now home to somewhere between 40,000-50,000 people.

Going by the plethora of signs, boards and banners, this camp has no shortage of aid agencies. But after a year under canvas and leaking plastic, some here are not impressed.

"Sometimes I feel angry because we are sleeping under plastic sheeting, and we get wet every time when it is raining. We are living in mud, we are living in garbage," says August Cassandra, a pregnant 18-year-old mother with a two-year-old.

"A lot of people are telling us that NGOs receive a lot of money. For me, they never do anything for us."

Armed with a megaphone, an aid worker from Oxfam roams the squalid and depressing looking camp giving advice on hygiene.

Cholera, which has so far killed about 3,400 people, is yet another fear that people here did not have before.

In the area that used to be the national theatre, but is now just a vast collection of tents and rubble, another danger stalks the country.

This, I have been told, is a very unsafe place for young women and even young girls. Rape, here, is very common.

"I was trying to resist. One of them pushed me, and they tore my dress and my skirt, and one of them raped me. And then the other two came and they did the same thing," Kerlange Pierre, 22, tells me.

"After they'd finished, they tore down the plastic sheet covering me. They had beaten me before they raped me, and then they beat me afterwards."

Kerlange had to spend several weeks in the same place with her newborn baby before she finally got help from Kofaviv, a local support group for rape survivors.

According to Amnesty International, who last week published a report on camp rapes, Marie's case was just one of 250 reported attacks in the first five months following the earthquake.

"The big problem we have in the camps now is that they are really not well lit at night when a lot of the rapes are happening," says Kofaviv spokeswoman and rape survivor Marie Devla.

"Sometimes we have cases where girls as young as four or five years old are being raped."

The UN has taken much of the blame for the political unrest and cholera outbreak

What everyone here wants is a plan for reconstruction, a feeling that things are moving in the right direction.

While I was in the country, former US president and UN special envoy to Haiti, Bill Clinton, arrived by helicopter.

Mr Clinton, who is also co-chair of the Interim Haiti Reconstruction Commission, which decides how reconstruction funds are spent, called for patience.

But that is something there seems to be less and less of as time passes.

"Is there a plan?" asks former Prime Minister of Haiti Michele Pierre Louis.

"They have approved a lot of projects. Is there a coherence between these projects? What's the plan for the reconstruction that the people are talking about?" she asks.

If there is a plan, she says, she hasn't heard of it.