How does a country change its time zone?

- Published

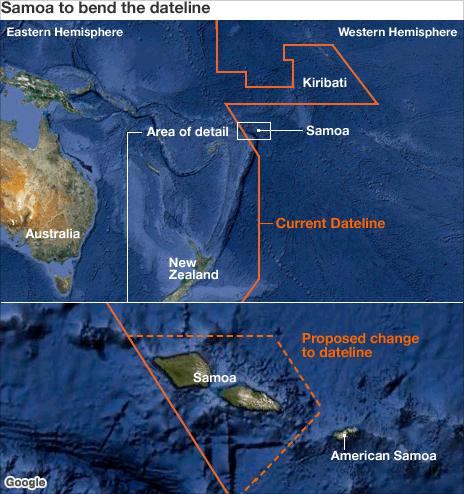

Samoa plans to move itself from one side of the international dateline to the other, redrawing this already wobbly line. How does a country go about changing its time zone?

Samoa sits in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just 32km (20 miles) east of the international dateline.

On Samoa's side of this imaginary line that runs from pole to pole, it is Tuesday. On the other side, it is already Wednesday. And this makes it tricky to communicate with its key neighbours Australia and New Zealand, a day ahead on the other side.

So Samoa plans to reset its clocks and calendars when it shifts the dateline - probably on Thursday 29 December, Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi said.

Samoa will lose a day as it jumps straight from Thursday to Saturday. Any residents with a birthday on Friday 30 December will have to celebrate a day early, or a day late, as that date will not exist in their country.

"There is no body that can say yes or no," says David Mumford, of Collins Bartholomew, which publishes the Collins and Times atlases for HarperCollins.

"The country decides for itself. Then it's just a matter of publicising it, informing the international community and the map-makers."

In mid-April, a Samoan official made contact with the cartographers at Collins Bartholomew, alerting them to the proposed change and asking who else might need to be informed.

"There have been various deviations and enclaves over the years, so we need to keep an eye out for proposed time zone changes. Once these go ahead, we update our atlases," says Mr Mumford.

Who set the time?

The dateline, and standard time zones in convenient hourly chunks, dates from 1884's International Meridian Conference.

It agreed upon a 24-hour clock for the world, with days starting at midnight at longitude 0º - a prize awarded to Greenwich, in London. This meant longitude 180º - the imaginary dateline which separates two consecutive calendar days - would run through the Pacific Ocean.

Nor did the meridian conference specify the exact course of the dateline.

It zigs and zags as it crosses land or passes through island groups. It kinks east to encompass Siberia within the same date as the rest of Russia, and west to bring Hawaii into line with mainland US.

Over the years, many countries have ignored this international standard and set their own time as a way to assert national identity, to make political connections, or to keep one time zone within their borders.

Some opt for local time based on the position of the sun, says Rebekah Higgitt, curator of the history of science and technology at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

In 2007, Venezuela's president Hugo Chavez shifted the entire country back 30 minutes. And France used to be on Paris time, nine minutes ahead of GMT. But the country is now GMT+1.

"A switch can make historical records confusing, and may cause headaches for legal cases, but most people won't notice," says Ms Higgitt.

Swapping sides of the dateline is not a first for Samoa. It, and neighbouring American Samoa, lay west of the dateline until 1892, when a US businessman convinced both to switch to the east for trading purposes.

The last country to shift the international dateline was Kiribati, which previously straddled the dateline, meaning a time difference of 23 hours between neighbouring islands.

So on New Year's Day 1995, it declared it was adding a huge eastward bulge to its section of the dateline so all 33 islands would have the same date.

"It was an administrative convenience," says Michael Walsh, the Kiribati Honorary Consul to the UK.

"There were nine islands on the other [eastern] side of the international date line, and 20% of the population. An unintentional byproduct of this was that when the millennium came, we were the first to see the sun."

There were few practical problems, he says. The eastern-most islands were uninhabited, with no infrastructure. "We just did it and told the world. Some atlases took a while to adjust."

Kiribati's decision did prove somewhat controversial, says Roger Pountain, of Collins Bartholomew, as some believe the dateline is a global standard, and therefore a matter for the international community to decide.

"It is still the case that some cartographers, website owners, and even public authorities continue to prefer to show the dateline as not diverted round Kiribati, while also acknowledging that Kiribati's time zone conflicts with that," says Pountain.

Samoa may yet find itself in a similar position.

- Published9 May 2011