Profile: Fethullah Gulen's Hizmet movement

- Published

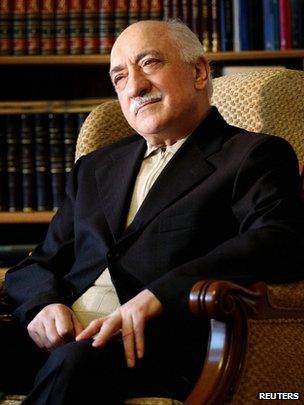

Mr Gulen has been in the US since 1999

Supporters regard the Hizmet movement inspired by US-based Turkish preacher Fethullah Gulen as the benign, modern face of Islam, but critics question its motives.

The influence of the movement has been in the spotlight again in Mr Gulen's home country, where a feud between his followers and other members of the political class has been blown into the open by a series of arrests.

Ill-feeling is said to have grown since the Turkish government moved to close down a network of private schools run by Hizmet.

Until then, the movement played a part in driving the electoral success of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Islamist-rooted AK Party, which has been in power for three terms.

But the movement's influence extends far beyond Turkey, funding schools, and think tanks and media outlets, from Kenya to Kazakhstan. It has attracted millions of followers and billions of dollars.

Key positions

Hizmet has no formal structure, no visible organisation and no official membership, yet it may have grown into the world's biggest Muslim network.

Its name means "service" and it promotes work for the common good, with advocates saying they simply work together in a loosely affiliated alliance inspired by the message of Mr Gulen.

The imam promotes a tolerant Islam which emphasises altruism, hard work and education.

There are said to be millions of Hizmet followers in Turkey, where they are believed to hold influential positions in institutions from the police and secret services to the judiciary and the AK Party itself.

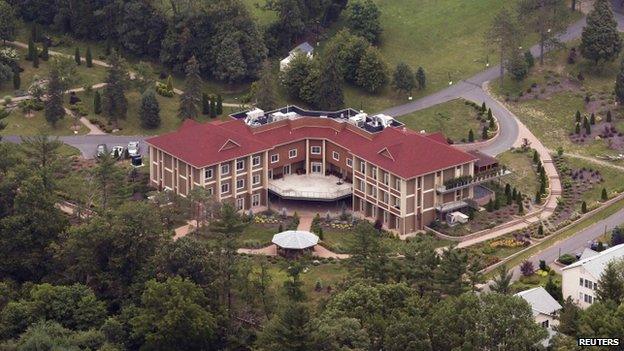

Mr Gulen lives in his retreat in Pennsylvania

Followers are said to donate between 5% and 20% of their income to groups affiliated with the movement.

The movement's schools usually boast hi-tech facilities, and many students are on scholarships funded by Gulen-inspired businessmen.

Although the schools are secular, teachers are expected to act as role models. Smoking, drinking and divorce are frowned upon.

Business dividends

Fatma Disli first came across the movement at a school it founded to help students pass university admissions tests.

"The people I met through Hizmet were really hard-working, virtuous people who were practising their religion, but at the same time had important jobs," she told BBC News.

"I realised that it's possible to be religious and to have a career."

Turkish businessmen are attracted by what they see as Mr Gulen's international outlook and pragmatic approach to issues like using credit.

The mix of philanthropy and business appears to have been powerful, with Gulen-inspired schools supporting and smoothing the way for Turkish businessmen in emerging markets like Africa and Central Asia.

However, critics believe the movement's aim is to gain power, to spread socially conservative Islamic attitudes on issues like marriage and alcohol around the globe, and to suppress any opposition.

Infiltrators?

Opponents of the movement point to a video which surfaced in 1999, in which Mr Gulen seemed to tell his followers that they should deliberately attempt to infiltrate mainstream structures:

Protesters accuse Gulen followers in the Turkish police of committing crimes

"You must move within the arteries of the system, without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centres.

"You must wait until such time as you have got all the state power, until you have brought to your side all the power of the constitutional institution in Turkey."

The following year, Mr Gulen faced charges of trying to undermine Turkey's secular state.

He left for the US, saying the recording had been tampered with. He was later cleared in absentia of all charges.

Several of Hizmet's most prominent critics have been jailed in Turkey, sparking claims that it has become a sinister controlling force in its native land.

A police chief who wrote a book on Gulen's influence on the police and judiciary was jailed, as were two Turkish investigative journalists.

One of the journalists, Ahmet Sik, shouted during his arrest: "Whoever touches them burns!"

Today, aged 72, Mr Gulen lives a reclusive life on a country estate in Pennsylvania, in the US.

He urges his followers to build schools instead of mosques, and encourages interaction with people of other faiths through dialogue societies, including one in the UK.

However, he continues to attract suspicion from supporters of the secular state in Turkey, and activists picketed his estate this summer.