False economy of skimping on Afghan forces

- Published

- comments

As we have heard many times, the exit strategy for Afghanistan relies upon setting up substantial local security forces to take over.

With leaders of Nato and other donor nations heading for a summit meeting in Chicago on Sunday, there are clear signs that an Afghan "Plan A" is no longer possible because people no longer feel able to fund it.

So US and Nato officials are now talking about leaving behind Afghan forces of around 230,000 rather than the 350,000 originally planned.

Experience suggests this is the worst kind of economy to make, when you are preparing an exit from that particular country. It is also a good measure of the gap between the rhetoric that many leaders have used about security there and what they are willing to pay for in these difficult economic times.

It has been clear since the US-led coalition toppled the Taliban government in 2001 that Afghanistan, which has never had a system of income tax, cannot produce the state revenues to sustain large security forces.

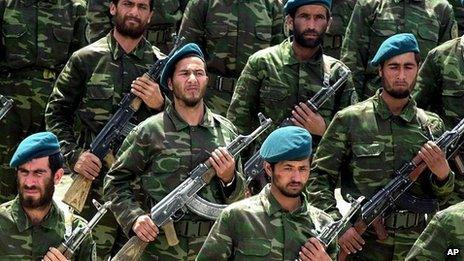

It was an attempt to produce a sustainable solution that led the foreigners to form an Afghan National Army (ANA) that was initially just 38,000 strong - a completely inadequate number for such a large and indeed heavily armed country.

As the insurgency worsened, plans were made to increase these forces. I recall being briefed by a Pentagon official several years ago, who told me that an Afghan army of 100,000 would cost £2bn per year to run, and that the country had an annual government revenue of just $700m at that time.

Since 2006, the ANA has been boosted well over that figure, and large numbers of police have been recruited too. Nato has been paying for almost all of it.

In recent months though, the Coalition has had to step back from its higher target (350,000) because its projected cost of $7bn annually was well beyond what Afghanistan is able and its international partners were willing to pay.

The new target, 230,000, is budgeted to cost $4.1bn each year, and in Chicago US President Barack Obama will be rattling the collecting tin.

When the Soviet Army left Afghanistan in 1989 it left behind 350,000 Afghan security forces under the Najibullah, external leadership in Kabul. How on Earth could he afford it?

The answer is complex but there were two key differences in his situation: Afghanistan had national service at that time so his foot sloggers were paid a pittance (if they got paid at all), and in many parts of the country his sub-commanders were allowed to "tax" passing traffic using the main roads in order to sustain their operations.

Najibullah managed to hold on to power for three years and defeat the mujahideen with those forces, defying those who had predicted he would not last a week without Russian troops.

When he fell in 1992 it was because his security model could not be sustained: the fall of the Soviet Union meant military aid was cut off, and one of his generals, Abdul Rashid Dostum, following arguments about collecting money from travellers on roads in the north, mounted a military coup. Dostum became one of the country's principal warlords during the ensuing civil war.

If this does not serve as enough of a warning to Nato and its friends not to skimp on Afghan security, let us not forget the British Army's disastrous retreat of 1842, external. A sole survivor from a column 16,000 strong (4,500 troops, the rest were camp followers of different kinds) reached Jalalabad after a series of running ambushes in snow bound passes between Kabul and that eastern city.

Much of the opposition had come from tribes previously fighting on Britain's side, but angered because their money had been cut off as an economy measure.

It may well be that the rundown of Nato forces actually leads to a drop in the level of violence across the country and that 230,000 troops and police prove perfectly adequate. But given the country's recent history, it would have been better not to take the chance.

It is clear though that raising even $4bn per year will be hard - and that is before the passage of time and fading of headlines has eaten into the willingness of governments to meet their agreed share.