Regional impact of Egypt military's declaration

- Published

- comments

Egypt's generals have waited months, until societal expectations of a brighter future have evaporated, to move

CAIRO: An announcement by Egypt's ruling military council that it has granted itself sweeping new powers has led to talk among those who made last year's revolution of a "constitutional coup", and the country's "official transformation into a military dictatorship".

So, if we watched the toppling of former President Hosni Mubarak with such interest because of this country's traditional role as a leader of the Arab world, how should these events be interpreted, and what might their influence on the region be?

It has been clear from the outset that the vested interests represented by the military and security agencies in Egypt were ready to use a broad range of tactics, with violence just a small part of the spectrum, to protect their stewardship of this country and its wealth.

Forcing Mr Mubarak's ouster or putting him on trial were just as important as tools in their struggle as any attacks on the protesters might be - arguably more so.

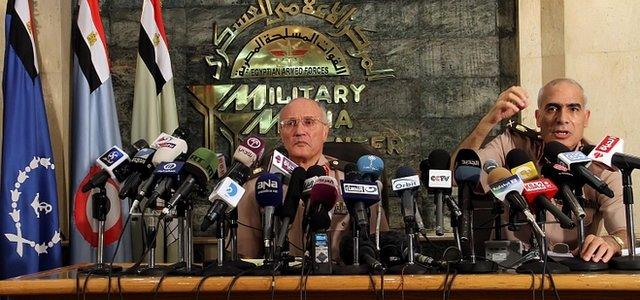

In the past week, the striking steps taken by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf) and its allies in other parts of what people here call the "deep state" involved the pen rather than the baton.

Last Thursday, the Supreme Court, with its roster of Mubarak-era justices, declared the recent parliamentary elections (in which the Islamists had swept the board) to be null and void.

Late last night, Scaf decreed that it would retain powers to set the national budget, appoint senior security figures, and, vitally, to convene a body to draft a new constitution.

With these steps all previous calculations, notably that Scaf itself would stand aside on 1 July, have been overturned.

The key aspect of these latest steps is their non-violence - particularly if one compares the actions of Egypt's generals to the way Libya's Gaddafi or Syria's Assad dynasties tried to crush dissent.

There is a difference with some other Arab countries, namely the strength of the military as an institution with interests distinct from those of the national leader.

Tunisia's army is weak, so the elite there has yielded to the Islamists at the ballot box, while Syria may have strong forces, but the Assad family has spent decades neutering the high command and packing it with placemen.

Talking on Sunday to General Sameh Seif Elyazal, a former boss of one of Egypt's intelligence agencies, I asked him about the constitutional safeguards the army would seek here regardless who won the presidency:

"The president cannot be allowed to declare war without the agreement of the armed forces", he replied, "and the scrutiny of the military budget should be limited to a very small group within the defence and national security committee of parliament".

These provisions, the first designed to stop an Islamist leader waging war on Israel, the second to prevent any detailed debate about the size or cost of the military establishment, sit uneasily with any Western concept of democracy.

They are however indications of the military's determination here to protect its interests - ranging from war fighting to the number of lavishly equipped officers' clubs or the involvement of military plants in many sectors of the civilian economy - from all comers. Of course the powers claimed by Scaf on Sunday go well beyond even this.

There are some Arab countries, Algeria is one example, where the strength of the military means they will monitor the Egyptian experiment closely.

It may also be that Iraq, where there were similar traditions of a strong army, may revert more closely to type.

In countries where a royal family forms the central pillar of power there are still some techniques that could be copied if dissent was to reach serious levels; from dropping an unpopular incumbent to the reversal of apparent concessions.

Egypt's generals have acted slowly in pushing back against the revolution. They waited many months, for societal expectations of a brighter future to evaporate, the economic situation to deteriorate, and for the people to become more cynical about what elected leaders might achieve.

The fact that turnout in the first round of this election was less than 50% may have given the military an indication of public weariness. Estimates of voting over the weekend are even lower, around 40%.

Of course the Muslim Brotherhood will respond to what one of their officials has called a "soft coup". It will fight to carve an effective role for Mohammed Morsi, the apparent victor of this election, and to reinstate the MPs sacked by Thursday's supreme court decision.

It may well bring hundreds of thousands of supporters onto the streets to confront the military.

The liberal opposition too will attempt to find a new role, and to ensure that Scaf's latest actions face some sort of challenge.

"Fight or flight, there is no going back", wrote the blogger Sandmonkey today, "the next chapter begins now".