Tunisians' frustrations, two years on

- Published

Tunisia two years after revolution

Two years ago this month, Mohammad Bouazizi, a young fruit and vegetable seller in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, made headlines around the world when he set himself alight, sparking a revolution in his country and a wave of Arab uprisings.

The Tunisian town of Siliana is just as poor, and resident Hamdi Garmzi just as desperate. But no-one is taking much notice.

Mr Garmzi, 44, has tried to kill himself many times to escape his life of poverty and pain.

A camel brown cloak draped over his hunched shoulders, he's now on hunger strike outside the governor's office in Siliana.

The patch of grass around him is strewn with medical certificates, and a folder of grisly photographs from when he set himself on fire years ago.

Like Bouazizi, his cart was confiscated by police. Mr Garmzi opens his cloak at the neck to show me some of the scars which cover his body.

"Nothing has changed here," he says angrily. "Not even after Bouazizi set himself on fire."

Just down the street, the Hollywood Cafe is packed with young unemployed men who feel much the same.

"Nothing, nothing has changed," Halmi insists, as he perches on a stool outside the Spartan cafe which does not live up to its glitzy name.

"There are no jobs. All the revolution gave us was freedom of expression."

"Life is just rubbish," blurts out his friend Adnan with palpable bitterness as he draws a deep breath on yet another cigarette.

The lavish palace has displays made from ivory and gold

'Nightmarish' scenes

That anger boiled over last week in protests on the streets of this deprived town in a farming region two hours south of the capital Tunis.

Police used tear gas and shotgun fire. Some 300 people were injured and resentment deepened.

"The people of Siliana are not violent," remarked local teacher and activist Rachid Kharroubi. "It was nightmarish for me to see how it turned violent so quickly."

The streets of Siliana are quiet now but Tunisia's powerful trade union, the UGTT, which organised the protests in several cities, has called for a rare nationwide strike this week.

Some government supporters say remnants of Ben Ali's regime are behind recent unrest

In a country long known for labour activism, it will be only the third general strike since the union was formed in the 1940s.

It comes after the UGTT accused the League for the Protection of the Revolution of attacking its recent march in the capital with knives, sticks, and stones.

Union leaders describe the league as an armed wing of the ruling Ennahda party, a moderate Islamist group that dominates Tunisia's post-revolution government. It is demanding that the league be disbanded.

Ennahda strongly condemned the attack.

Accusations are now being hurled in both directions. Government supporters took to the streets in Tunis on Saturday to paint the UGTT as an enemy of the revolution.

Some waved copies of an old photograph showing union chief Hocine Abbasi shaking hands with the ousted President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali as proof that remnants of the former RCD ruling party were still active.

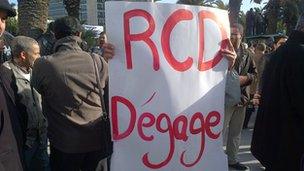

"The revolution is in danger," one man warned as others shouted the slogan that dominated protests two years ago: "RCD degage! RCD get out!"

Identity crisis

Many Tunisians regard such pitched political battles as a costly distraction from more pressing issues, including the growing poverty and sense of injustice that fuelled the revolution.

In one of the most progressive countries in this region, left-wing and liberal groups are also worried about the rising influence of more hard-line Islamist Salafist groups.

Salafists have unleashed their zeal in a series of attacks, including most recently the US embassy in Tunis in September over an anti-Islam film, and against a gallery whose art was deemed offensive.

Most of the people Lyse met in this cafe did not have jobs

Many Tunisians, in a country regarded as a stronghold of Arab secularism, see the Salafists and more moderate Ennahda as one and the same.

"Ennahda came to power legitimately though elections," says retired Ambassador Ahmed Abderraouf Ounaies who served briefly as foreign minister last year.

"They tried to impose their views, but they are now fully aware that they have to come to a compromise with modern Tunisian society."

Ennahda's leading architect of change, 71-year-old Rachid Ghannouchi told me: "If we want the transition to succeed we need moderates, in all camps, to work together."

"We don't believe the state has the right to impose its views on what people wear, eat or drink, what they should believe in," he insisted.

Does he worry the revolution he joined when he returned from a 20-year exile in London, might fail? "A revolution is a like an earthquake, it takes time to form a new landscape," he said.

Bellwether state

But even the icon of the uprising that inspired an entire region is now losing his allure.

Mohamed Bouazizi's family was forced to leave Sidi Bouzid as resentment grew over their fame, as well as dashed hopes.

"People thought we received billions in money," reflected his indignant mother Manoubia as she prepared dinner in a new home they are now renting in a Tunis suburb.

"Now people realise that we didn't get any help from the government, just like everybody else. All the mothers are still grieving."

The evolution of Tunisia's "Jasmine Revolution" is often seen as a bellwether for the region.

The north African nation was the first to oust its authoritarian leader and the first to hold peaceful elections last October which created a power-sharing agreement between Ennahda and two secular parties which control the presidency and the prime minister's office.

"Getting rid of Ben Ali was somehow easy," explained Slim Amamou, one of the radical young activists who played a key role in organising the protests after Mohammad Bouazizi's self-immolation.

"It's very tedious work in the long term to change things.

"Of course we can lose but we will keep trying," Mr Amamou remarked. "We will win in the end."

Mr Ounaies, at 76 a voice of a different generation, shares that confidence. "Tunisia has all the strengths to build a democracy," he said.

But for now, each new battle on the streets still shakes the confidence of many in Tunisia and beyond.

- Published10 December 2012

- Published28 November 2012