Amid scars of past conflict Spanish far right grows

- Published

- comments

A withered wreath lies on the site where two thousand three hundred people died

Valencia, Spain: You go down a track, cross a puddle and enter a low pine forest, strewn with fly-tipped construction waste, cigarette packets, beer bottles. You find a track big enough for an open truck to get down. And there's the wall. It is about three feet (one metre) high, faced with concrete and full of bullet holes.

This is the wall against which, between 1939 and 1956, two thousand three hundred people were executed. They were Republican prisoners, brought from jail in batches of fifty - men and women on the losing side in a civil war.

At the base of the wall there is a crisp and withered wreath draped in the colours of the old Spanish Republican flag, laid by the "Socialists of Paternas", the area of Valencia we are in. Last year's wreath lies discarded. And that is it. No sign to explain. No official curation of the site at all.

"The victims are paid homage only by friends and family," says Matias Alonso, my guide; "Officially this place doesn´t exist."

Mr Alonso is one of the unofficial curators of the site. For him, the state of the place demonstrates modern Spain's big problem with the Civil War: it has officially been forgotten.

In the wake of Franco's death an amnesty law was passed covering crimes committed under his regime

General Francisco Franco died in 1975. Two years later, as King Juan Carlos oversaw the transition to democracy, an amnesty law was passed, forbidding the investigation and prosecution of crimes, not just during the Civil War, but throughout the entire Franco regime.

In 2007 the-then socialist government passed the Historical Memory Law, promising state help in the finding and exhumation of mass graves.

But historical memory in Spain is a politically contested space: the Partido Popular, which now governs Spain, opposed the Memory Law and promised "not one public euro for the exhumation of mass graves". They have now cut funding.

For Mr Alonso, a socialist who worked clandestinely during the last years of Franco, the problem is not about history, or memory, but about now.

Spain has decided to re-live the 1930s, economically, inflicting the biggest austerity programme in modern times on an economy where there is already 25% unemployment. Mr Alonso believes the failure to "de-Nazify" the old political elite in the 1970s poses a danger today:

"There is a big danger. When there are people in the government and the city halls that have not rejected the values for which many democrats were killed, nobody can make sure that - when the crisis hits - they don´t take their modern suits off and come out with their [fascist] blue shirts and the killings start. And that worries us."

I have been reporting the Spanish crisis for the past two years and it seems to me, up to now, that the institutions of Spain have been resilient. If it is true that, among the octogenarians of the business elite, there are people with a fascist past, it is also true that the compromises made in the 1970s have held.

The socialist PSOE and the conservative Partido Popular (PP) have alternated in power for decades; and as the economic crisis has hammered Spain there has been no rapid emergence of a hard religious right-wing party, such as Laos in Greece, and no mass fascist movement such as Golden Dawn.

Newsnight's Paul Mason visits Valencia in Spain and finds wounds from the Franco era are in danger of re-opening.

Meanwhile the Communist Party, which prospered in the post-Franco political truce, is growing.

But if you get down to Cabanyal, the tough working class area at what used to be Valencia's dockside, you can see the threat to the status quo.

In the boxing ring, Sento "Tsunami" Martinez is showing one of his pupils where the Tsunami bit of his name comes from: he is showering a tidal wave of blows into the target gloves, as another twenty or so young guys hammer the punch bags and pour sweat.

These are young working-class men and the crisis has hit them hard. The official statistics say 50% of Spanish people under the age of 24 are jobless. Sento reels off some other stats that show the impact:

"Four years ago there were ninety professional boxers. Now there are two hundred. So one hundred and ten boys have gone from amateurs to professional boxing because they need the money. What you get is not much, but it helps now with the crisis."

But the value of the fight purse has fallen. If you can go six rounds with Sento you can earn maybe 1,200 euros - enough to live on for a month. Sento, with the lean, punched face and intense alertness of the trained fighter, does not look like a man anybody could go six rounds with:

"Many of the boys that come here cannot pay for the gym so I train them for free. I'd rather have them here than on the streets robbing, on drugs or anything else. We have a sporting and healthy atmosphere, discipline and a routine."

But Sento is no ordinary fighter. For him, this combination of slugging and social work serves a higher purpose: "I am a national socialist," he tells me cheerfully. "My hero is Rudolf Hess."

"This is not a democracy, this is a dictatorship that they have built up, and that is Spain´s problem," he tells me - referring to the two-party system that many here believe is the root of Spain's vast corruption problem.

The answer? "I'd go for a revolution. Not from the left but from the right. I believe in a national revolution."

Sento is a supporter of the far right party Espana2000. It has been a small current up to now, run by people who were trying to practise right wing street politics even in the last days of Franco. But now it is recruiting fast, 70% of its membership is young, male and working class.

And for Sento "Tsunami" Martinez, the word revolution has a specific meaning:

"As long as people have food there will be no revolution. The revolution will come when there is no bread left. Then we will see shootings and everything."

For now, there are no shootings. But there is action. On 15 November 2011 Espana2000 organised a march to close down a small mosque in the nearby small industrial town of Onda. The party's own video of it shows a disciplined march with lighted torches, under the banner "Stop the Islamic Invasion."

The police prevented the demo passing the front of the mosque, which serves mainly migrants from North Africa.

In September this year the mosque was firebombed, when somebody poured lighter fluid through the door and set it alight. Espana2000 says it had nothing to do with the attack. The police have failed to identify the attacker.

Inside the mosque, one of the teachers there, Mohammad Hicham, tells me the whole experience has made them scared. What is causing it is "the crisis", he says, is the lack of jobs for local people and their lack of understanding of the past:

"In North Africa we study the history of France and Spain. We know what went on under Franco. Sometimes I think the Spanish people, especially young ones, do not know what went on at all."

Espana2000's leader is Jose Luis Roberto. He is a veteran of the far right, arrested but acquitted during the last days of Franco during a bombing campaign. He is a lawyer; he is also the head of the security industry body in Valencia, and runs several gyms, a security firm, and shops selling uniforms to the police.

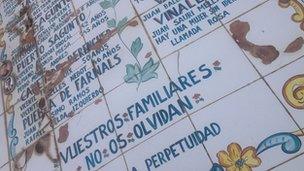

In Paternas cemetery the families of those killed have been allowed to mark their mass graves

I meet Mr Roberto in the community centre the party has set up in one of the poor neighbourhoods of Valencia. It is a courtyard, with a second hand toy and clothes stall and in the corner a big paella pan bubbling on a wood fire. This is for the soup kitchen the party runs, for those on the breadline. It is also a library, and has five rooms for people who have become homeless. We do not serve "Moors" he tells me, meaning Arabs.

As Mr Roberto gives me a tour I notice cards celebrating Gen Franco displayed, alongside much heraldry concerning Spain's monarchic past, and firearms magazines on the coffee table:

"The image of Franco was a lot worse 20 years ago than now. People realise that they had a job, a house, worked like crazy, but managed to even have a second house, they could pay for their children's education... old people see that. The ones who lived in his time, they see it. Many people not just in Espana2000, but in the PP and PSOE, see Franco positively now. He never took our Christmas pay away."

Mr Roberto explains his party's programme: import controls, reducing the power of the autonomous regions, the creation of "one big Europe" involving Russia. On social services he tells me:

"We would establish a preference for Spaniards, Spaniards would be the first ones to get everything."

The party's social makeup is mainly working class, and its target areas are the poor housing estates. It rejects the label fascist:

"They criminalise us and say we are evil. People come to us and see we are not that way. We are growing because people talk about us and more and more people come to us. Around 35-40 people are joining us every week. In a country where people are disappointed with politics that's good. There will be a moment in which this will take off."

I challenge him on the anti-Mosque demo, in the context of the firebombing:

"Espana2000 are not the only people affected by the mosque. It could have been anyone. We are against the burning of the mosque, but if a member of Espana2000 or a neighbour in their private life did it, we are not responsible."

I ask if he regrets the firebombing: "We don´t speak for others, it is not our business. If somebody did it he must regret it, we cannot regret it," he says.

Right now the party is assembling the activists and establishing a small local presence on elected bodies, just as the much bigger Golden Dawn party did in Greece. Its profile - in the security industry, in boxing gyms and military apparel stores - is very similar to that of the core grouping that leads Golden Dawn.

I put it to him that it is playing with fire to use torchlight parades, Francoist imagery in a country that had a civil war and where social conditions are leading to unrest:

"Playing with fire? Have a look at people here. When people are leaping off their balconies because they can´t feed their children; where young people don't have a future, are we playing with fire? We will probably end up playing with fire as politicians are leading us to a situation in which we will end up having a social revolution."

"We will use all democratic ways... But if we reach an extreme situation we will have to hit the streets and use the force if necessary to avoid people from being in that situation."

How will he know it is time to use force, I ask the veteran far-rightist?

"It is like carrying a gun. When you have one, how do you know when to use it? The best thing is not carrying it or not using it. But when you have to use it you just know. Obviously it is not the right time yet, but when it comes, we won´t need to have a meeting to discuss it, we will just know."

In the cemetery at Paternas, just a couple of hundred yards from the execution wall, there is a reminder of what happens when people resort to force instead of democracy.

Plots, twelve feet square, each containing one day's worth of executed prisoners. The families were allowed to state their name and place of birth on the collective tombstones, but not the cause of death. On the plot marked 17 November 1939 I counted 53 names including "an unidentified woman known as Rosa".

Nearby, under an awning, Matias Alonso and his colleagues have an exhumation in progress. Beyond the main graveyard there is a wide plateau which Mr Alonso believes contains the bodies of maybe one thousand more victims. Due to the withdrawal of government funding it will not be exhumed.

The Spanish Civil War killed maybe three hundred thousand on the battlefield with both sides indulging in post-combat executions running into tens of thousands. After the war there is no adequate account of how many were executed, but there are more than one hundred thousand missing persons from the post-war period.

Some of the surviving families of those killed have erected proper tombstones as well

Today, the surviving families at Paternas have erected smaller individual headstones, including photographs, on the top of the collective ones. Standing there amid the birdsong and plastic flowers is a sobering experience.

The small oval portraits show men who did not need to be politically radical to get shot. Though some were Communists, others were socialists or liberal republicans: they were fighting for democracy. And the dead were generally killed in their 30s, 40s and 50s - not the classic age profile of the combatant.

In Germany, and the lands it occupied during World War II, there are huge and moving memorials to the victims of fascism. The "execution wall" at Auschwitz has become a site of pilgrimage for democrats and opponents of racism. And in some European countries denying the Holocaust remains a crime.

In Spain, forgetting who did what under Gen Franco is the law. And the execution wall at Paternas is hidden within a rubbish dump.

There were strong reasons for what is now called the "Pact of Forgetting". It seemed to allow Spain to democratise rapidly - and with European Union and euro membership, and prosperity, there seemed little chance that the old wounds would be re-opened.

But the economic and social conditions that underpinned that assumption are unravelling. The street actions of the far right and far left are ramping up - with mass demos by the unions and the so-called indignado youth regularly turning violent.

It may be that the legacy of the boom years, the strength of the Spanish two-party system, or simply cultural differences make it impossible for a Golden Dawn-style breakthrough for the right in Spain.

But it may simply be that Spain got bailed out in a softer and more intelligent way, in a move designed to preserve political consensus rather than destroy it, as happened in Greece.

If so, the scale of anger and contempt I've found among the young while reporting from the streets of Spain this year points to one thing: that bailout had better work.