Afghanistan peace talks: 'The ball is now in the Taliban court'

- Published

"By the end of next year, our war in Afghanistan will be over," declared President Obama to thunderous applause during his State of the Union address this week.

This was a speech about ending an unpopular war and bringing US troops home, not about winning a peace, or even trying to negotiate one.

"We are still hopeful we might enter talks but we didn't want to raise expectations," a senior US official told me. "The ball is now in the Taliban court."

The Taliban suspended unprecedented talks last March with an angry statement describing the US as "shaky, erratic, and vague".

They accused Washington of making unacceptable demands during a series of meetings, meant to be secret, to work on "confidence-building measures".

For the Taliban, it was about freeing five prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay.

For the US, it was the release of Bowe Bergdahl, their only soldier in Taliban captivity. There was also a demand for public Taliban commitments including an end to al-Qaeda links, and an agreement to talk to the Afghan government.

"The channel is still there, and we hope to pick it up again," said another US official with knowledge of previous talks.

US Congressional opposition to a prisoner release, and Taliban refusal to accept conditions or talk to what they say is a "puppet" government in Kabul, remain major hurdles.

For both sides, it's still about talking and fighting in the run-up to the US-led Nato troop pullout in 2014. And the main emphasis, for the Taliban and the Pentagon, is still on the war.

"There hasn't been a Northern Ireland moment," said one diplomat, alluding to a process where two sides accepted military means could not achieve their goals. "It is more like Colombia when the government and the rebels have started talking but keep fighting."

Trouble-shooter

A crucial element enabling what both Western and Afghan officials call "cautious optimism" is a more engaged Pakistan. Afghanistan's neighbour has long been accused of not doing enough to rein in Afghan Taliban operating from its soil.

Secretary of State John Kerry - the US trouble-shooter of choice

"I think it has finally sunk in that Pakistan's own security could be threatened by greater links between Afghan and Pakistani Taliban once most of our troops leave," said one US official.

In recent months, Pakistan has started responding to long-standing Afghan demands for the release of Taliban prisoners. But the process has not been coordinated with Kabul and prisoners have just dispersed. Some have returned to the battlefield.

The new US Secretary of State John Kerry has still not appointed a successor to Ambassador Marc Grossman who stepped down as Special Representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan at the end of last year. During nearly two years in the job, he became the most senior US official to talk to Afghan Taliban.

Senator Kerry has also not indicated publicly how much priority he will place on this region. But the well-travelled senator has long been the US trouble-shooter of choice in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

He was the point man on major crises ranging from the arrest of a CIA agent in Pakistan in 2011 to the explosive row over controversial Afghan presidential elections in 2009.

US diplomats say, that as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Kerry kept in regular touch with the special US State Department office focusing on "AfPak".

A few years ago, he emphasised his agreement "with the fundamental premise that there is no military solution in Afghanistan". At the time, he spoke of "serious efforts" under way to achieve a negotiated end.

Secret meetings

The most serious efforts came at the end of 2011 and early 2012 in a series of secret high-level meetings involving Ambassador Grossman and Tayeb Agha, an aide to Taliban leader Mullah Omar who has been in hiding for many years. US officials say he proved he had authority to negotiate.

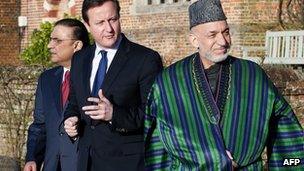

PM David Cameron met the Pakistani and Afghan leaders in the UK recently

The process, also involving German envoys, came close to a deal on opening an office for talks in the Gulf state of Qatar. But, at the 11th hour, at a summit in December 2011 in Bonn, President Hamid Karzai called off the plan, suspicious a deal was being done to undermine his government.

An office, or "address" in Qatar is still regarded as an important next step in formalizing a channel of talks.

The Afghan leader remains hesitant about the Qatar plan even though he publicly agreed to it during a meeting with President Obama in January and at a recent tripartite summit in the UK involving Britain's Prime Minister David Cameron and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari.

Britain, on the request of Kabul and Islamabad, is now more engaged in trying to galvanise a process of negotiations while Western troops are still on the ground.

The UK summit statement optimistically spoke of a peace deal in six months.

No-one expects it could happen so soon. "At least we, and the Pakistanis, now have a deadline to focus on," said one Afghan official involved in the recent UK talks.

As is often the case in Afghanistan, there are no formal talks, but a lot of informal talking, including in Doha and Dubai. Conferences, such as the Chantilly meeting organised by a French think-tank last December, also gathered Afghans from all sides.

But US engagement on a political track still remains critical. As one senior US official put it, "after all, we are a combatant in this war".