The media's darkest days remembered

- Published

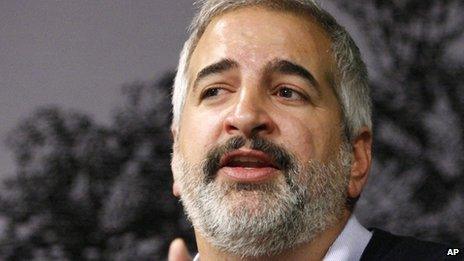

New York Times journalist Anthony Shadid died last February

It's one of those weeks when many in our global tribe will take a moment to reflect on our business. Journalism should not be about the journalists' own stories, but there are moments when it is.

A year ago this month, some of our best storytellers and cherished colleagues lost their lives on the job in Syria. On 16 February, Anthony Shadid of the New York Times died suddenly of an asthma attack on his way out of Syria.

The world lost a gifted chronicler who wrote with great authority and affection about the Middle East and beyond.

Five days on, late in the evening, one of the most prolific Syrian citizen journalists Rami al-Sayed was killed in shelling in Homs.

The next morning more terrible news came. An old friend and fellow traveller, veteran correspondent Marie Colvin, and young French photojournalist Remi Ochlik were dead.

Others, including Marie's colleague Paul Conroy and French journalist Edith Bouvier, were also badly injured when a house in Homs serving as an informal media centre came under rocket fire. Many Syrians perished with them in a government assault on an opposition-held area of Baba Amr.

Last year was a terrible year for the world's media. The Committee to Protect Journalists, in its annual report, recently announced that 28 were killed in Syria last year, making it the deadliest place worldwide to cover a story.

Seventy were killed on the job around the world, many more than the year before.

And in Syria, a number of journalists are described as "missing", including the American Austin Tice, last seen in August, and James Foley who went missing in November.

'Taking risks'

Last February, Marie Colvin who had seen the worst of too many wars, was given caring words of caution from friends and colleagues before she made the risky journey across the border into Syria. She acknowledged the danger, but insisted: "It's what we do."

Marie Colvin at a 2010 service commemorating fallen journalists

In an email to the BBC's Middle East Editor Jeremy Bowen 24 hours before she died, Marie wrote: "I am in Syria, freezing in Baba Amr. I thought yesterday's piece was one of those we got into journalism for. They are killing with impunity here. It is sickening and anger-making."

Almost two years since the start of Syria's uprising, the United Nations says nearly 70,000 Syrians have died. The number of refugees living in desperate conditions in neighbouring countries will soon reach one million. And millions are displaced, in need of assistance, inside Syria.

"The situation in Syria is nothing short of catastrophic," warned the Red Cross (ICRC) director of operations Pierre Krahenbuhl after a recent visit.

And this week, former UN prosecutor Carla del Ponte called on the International Criminal Court to launch an investigation into war crimes committed by all sides in Syria.

Anthony Shadid once said in an interview with National Public Radio: "I did feel that Syria was so important, and that story wouldn't be told otherwise, that it was worth taking risks for."

The agonising question he faced, as do many others, is deciding when the risks are just too great to go in search of a story that needs telling.