Literary festival brings feel-good factor to Lahore

- Published

Lahore is famed for its architecture - but has also seen militant attacks

"It's all about words."

So says the slogan of the Lahore Literary Festival, external, scribbled in the earthy shades of this city's exquisite Mughal architecture.

"Lahore has fired the imagination of writers, artists and thinkers over the ages," remarked Razi Ahmed, founder and CEO of the first literary festival in a city long regarded as Pakistan's cultural capital.

"We wanted to honour this Lahore," he said.

"If I toss up the word, and close my eyes, it conjures up gardens and fragrances," wrote novelist Bapsi Sidhwa who grew up in a city also cherished for its winding canals, magnificent mosques and graceful British colonial buildings.

Bapsi Sidhwa wrote acclaimed novels set in this city including Ice Candy Man, also published under the title Cracking India, which inspired the film Earth.

Wherever she went, 75-year-old Ms Sidhwa, now frail and delicate in her elegant Pakistani shawls, was surrounded by admiring fans of all ages.

Over two days, large crowds filled the halls of the Alhamra Art Centre to listen to lilting recitals of Urdu and English language poetry, and to delight in classical dance and music.

There was impassioned discussion of themes from "A Sense of Place", "The Holy Warrior and the Enemy" in film, music and media, and the globalisation of Pakistan's literature.

"The words have been beautiful," gushed 16-year-old Jazil proudly wearing a white t-shirt emblazoned with the festival slogan.

"When my principal told us we should volunteer, we thought we were too busy.

"But now all these words have come to us through this channel."

Thunderous applause

Zehra Nigah, the esteemed 76-year-old poet, delighted the packed halls with her evocative recital of Urdu verse.

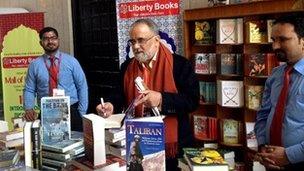

Author Ahmed Rashid signed books at the festival

"There were tears in her eyes when she saw all the young people applauding her work," marvelled artist and writer Salima Hashmi, Dean of the School of Visual Arts at the Beaconhouse National University.

Luminaries from Pakistan's growing club of young internationally-renowned writers turned out to read from their novels, along with other authors, including British historian William Dalrymple.

"This lets Lahore see what Lahore is," commented Mohsin Hamid, author of the Reluctant Fundamentalist who launched his new book How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.

Mohammed Hanif, a former BBC journalist who shot to fame with his first novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes, discussed his latest writing on the many who "disappear" in the volatile south-western province of Balochistan.

The collection of stories, published by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, is based on six true stories of Baloch who are missing and others who are not - "for the simple reason that they are dead".

"We hope words have power," he said.

But like many at the festival, he underlined that no matter how wonderful words are, they are not enough.

"There are still many kids in Pakistan who will never even see the inside of a school, who will never know the alphabet," he said regretfully.

"We still don't have a state education system that can educate every Pakistani," declared Lahore-born British-Pakistani writer Tariq Ali. A few years ago, a Unesco report highlighted how Pakistan spends seven times more on arms than on primary education.

"We have a bubble that many of you here live in," Tariq Ali admonished an audience, which responded with thunderous applause.

Sectarian violence

In recent years Lahore, like other major Pakistani cities, has also become synonymous with suicide bombings, and the growing presence of militant Jihadi groups who traditionally sought sanctuary in the tribal areas along the Afghan-Pakistan border.

Urban designer Attiq Ahmed says many different groups have found a voice at the festival

Coverage of the festival shared the front pages of Pakistani newspapers with more typical news fare such as calls for a crackdown against militant groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi.

The group is blamed for a resurgence of sectarian violence including a recent spate of killings in the south-western city of Quetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan.

Initiatives like this festival are efforts to reclaim a different narrative, and future, for this country.

"We want to institutionalise this literary festival," declared Shahbaz Sharif, Chief Minister of Punjab whose provincial capital is Lahore.

Mr Sharif also underlined the deep crisis, on many fronts, which has put Pakistan "on the brink".

But there was a palpable feel-good factor around the literary festival.

"So many disparate groups have found a voice here," said urban designer Attiq Ahmed who staged a photographic exhibition of Lahore's distinctive architecture.

Others used the occasion to highlight campaigns to urge young Pakistanis to vote in the upcoming elections, or to raise awareness on a range of social issues.

"You've been to the Lahore Literary Festival?" queried the police officer at passport control at the airport as I left Lahore.

"Do you still think this is a country of terrorists?" he asked, only partly in jest.

"I never did," I said. "And certainly don't now."