Spent force: Are wars still winnable?

- Published

US Marine Corps officers firing a mortar at a training range in Virginia

America is starting to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan and the implications of more than 10 years of fighting is far from clear. Is it possible to win a war any more or have wars always been unpredictable in their outcomes?

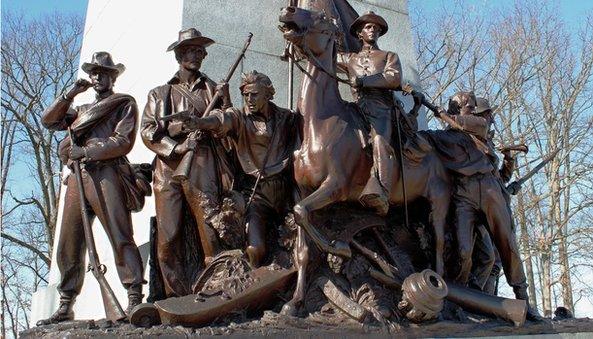

Gettysburg is one of the key locations in American history. Some 150 years ago in July 1863, the fields around this sleepy Pennsylvania town were the site of one of the pivotal clashes of the American Civil War.

For three days the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commanded by General Robert E Lee traded blows with the Union Army of the Potomac.

If you've never visited one of these Civil War battlefields, you'd be amazed how easy it is to follow the events of those fateful days. You can almost hear the sounds echoing down the years.

Old cannons mark where each of the artillery batteries stood during the battle and stone monuments indicate the place of each regiment in the line.

Artefacts like this cannon remain on the battlefield site at Gettysburg

Paul Marhevka, a local historian who conducts guided tours of the battlefield, insists that at Gettysburg there was no doubt as to the final outcome. "Gettysburg is a decisive battle," he told me. "It's Lee's first major loss. From now until the end of the Civil War Lee has no more victories.

"When Lee's army is leaving Pennsylvania heading back into Virginia, he knows that there's as many as 10,000 of his men starting to desert. So things are starting to go downhill in the South after Gettysburg."

Gettysburg did not in itself decide the course of the war, but it was a battle that probably determined that the Confederacy would not win.

'Profound lesson'

Today however, the outcome of armed conflict seem messier - more uncertain. In Iraq and Afghanistan there's been no definitive outcome, no clear victory or defeat. But Eliot Cohen, professor of Strategic Studies at Johns Hopkins University, notes that history is not always as clear cut as we think.

"I think anybody who's aware of the history of the Civil War," he told me, "will on the one hand think of it as a decisive conflict - it ended with a complete destruction of the Confederate states of America.

"But I think will also be aware that the fundamental issue over which it was fought, which was slavery, was in some ways not resolved for over a century.

"Even the Civil War - and Lincoln understood this perfectly well - did not fundamentally resolve the issue of the relationship between white Americans and African Americans. So there's a profound lesson in that."

A memorial at Gettysburg - it was the battle with the highest number of Civil War Casualties

Part of the problem is that we just do not seem to learn from history. Indeed US strategic analyst Prof Tony Cordesman, of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC, thinks that we are far too cavalier in talking about the application of military force.

"There was never a time when governments or the public understood the implications of war even when they were fighting them," he told me. "If they could have predicted the outcomes they either would have avoided the wars or certainly have changed the strategic objectives.

'Nature of war changing'

"One of the dangers here is in talking about the uses of force, it's a little like talking about the uses of economic aid. You can't control the outcome in many cases, you can't predict it."

It's not only that perhaps too much is invested in what military force can achieve. The other problem is that the nature of war itself is changing radically. I went to the US Marine Corps' training base at Quantico in Virginia. Here a new generation of young officers are being trained for this new era of uncertain conflict.

The man I had come to see was Lieutenant General Richard Mills, head of the Marine Corps Combat Development Command. Previously he was in charge of US and British troops in Afghanistan. Having been brought up in one era of warfare he was well aware of how different things are today.

He said: "In past wars - the historical wars we have all studied - it was government against government. Their aims were clear and the ability to defeat them was also clear.

"But with the instigation of war against non-state actors, where their intentions are less clear, where their centre of gravity is difficult to find and where the endgame is a little less clear-cut - that becomes very difficult for the military men."

The challenge of irregular warfare, he says, is to find that piece of the puzzle that will allow you to achieve what it is that you want to achieve which will cause the enemy to put down their weapon and return to their homes and which the conflict can end on a clear basis. "That's becoming more and more difficult," he said.

The military are becoming more and more aware of the limitations of the use of force in this new context but it's not clear that their political masters have made the same journey.

Prof Cordesman argues that military failings there may be, but the real problem lies elsewhere, in the unrealistic expectations of the political leadership.

"When you look at the failures in Afghanistan and Iraq there were certainly military difficulties, choices that probably should not have been made from the military campaign side, but the primary failures in these two cases came from the civilian side, from the assumption that you could change governments, that you could develop an economy quickly and easily, that you could teach governance or alter the basic values of ethnic and sectarian groups or ignore their differences."

Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia was established during the Civil War

For Prof Cordesman the real lesson of both Afghanistan and Iraq is the need for idealism to be tempered with pragmatism. "Do not turn these into moral crusades," he said.

"You may have to walk away. You may have to do it their way. You may have to tolerate evolution in societies where many of the social customs, human rights practices, are unacceptable in the West." If you try to do too much, too quickly, he says, "then the consequences are likely to be worse".

As America's decade of conflict draws to an end it's a time for reflection about the utility of force; can modern warfare within societies ever bring the tidy outcomes that policymakers strive for? It's a question that should have been asked in Iraq and Afghanistan; and it is as relevant in Mali and across much of sub-saharan Africa today. There may be no more decisive battles like Gettysburg.