On the campaign trail with Pakistan's rival politicians

- Published

"I've said no rose petals because people are suffering," Nawaz Sharif explains.

But as we step out of his four-wheel drive vehicle, the veteran campaigner is showered with crimson petals by an enthusiastic crowd.

A crescendo of "Wazir-e-Azam! (Prime Minister) Sharif" rises from excited loyal supporters. A few even push forward to slip fragrant garlands around his neck.

Old habits die hard in Pakistani politics. But this time, politicians are being forced to change. Taliban attacks have made the rousing road shows and rambunctious rallies of old simply too dangerous.

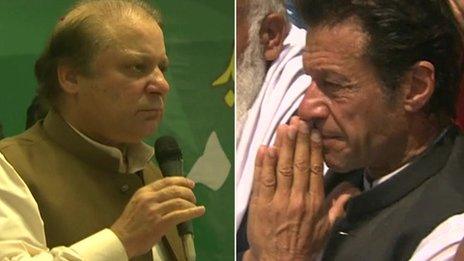

But two-time Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and rising star Imran Khan weren't on a Taliban hit list during what's being mourned as the bloodiest ever election.

The two men have been campaigning hard. And I joined them both on the trail in the past week.

Travelling with them, you're thrown into the chaotic carnival atmosphere of elections past.

But at most public gatherings, rowdy crowds are kept back at safer distance. Speeches are shorter.

Advisers place bullet-proof glass shields on podiums but both men make a point of removing them. They resist wearing protective armoured vests.

Family members say Imran Khan finally succumbed to their pleas, and will always be grateful he did. A vest cushioned his fall from a forklift at an election rally on Tuesday and, it's said, probably saved him from serious spinal injury.

Private jet

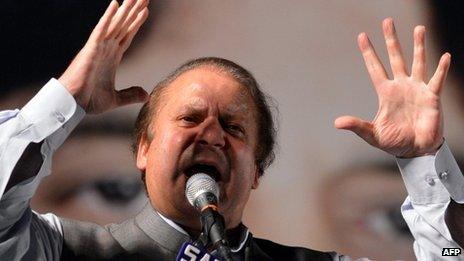

Nawaz Sharif on the campaign trail in Rawalpindi

As a closely fought campaign goes down to the wire in Pakistan's most unpredictable poll, Imran Khan is sending his last appeals from his hospital bed and Nawaz Sharif is sharpening his slogans.

Imran Khan's slogan of "Naya (New) Pakistan" has clearly excited large numbers of young voters and lured apathetic middle classes from their drawing rooms.

But Mr Sharif bristles at suggestions his rival has the monopoly on the magical mantra of "Change".

"Our slogan in the 1990s was a slogan of change," he tells me as we take off in a private jet that allows the wealthy industrialist to travel in style, speed, and safety. He cites how his Pakistan Muslim League had opened up the economy, and maintains he would have accomplished much more had both his terms not been cut short by coups and conspiracies.

"We have people, we have done it before," he emphasises. With a swipe at his rival, he adds: "We don't need immature people."

On the plane, his aides hand him the latest press clippings which predict he'll be the next prime minister. With a broad smile, he shows me a text he's received on his mobile phone - stock prices have risen to record highs on that expectation.

'Revolution'

Imran Khan addresses supporters before his fall

If one of Nawaz Sharif's selling points is that he's "good for business", Imran Khan is roaring to new political heights with a vow to end "business as usual".

He's already changed the usual ping-pong in Pakistan politics between Mr Sharif's Pakistan Muslim League and the Pakistan People's Party which once defined itself by "people power".

"This is the beginning of a revolution in Pakistan," Imran Khan exclaims above the screech of helicopter blades whirling for lift-off.

"This is an uprising from the grassroots. We've completely bypassed the traditional politicians."

On a whirlwind tour of the north-western province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which has seen the worst of Taliban attacks, I point out that he can hold these public gatherings because he hasn't condemned the violence.

"I am not pro-Taliban," he retorts as he prepares to address another rally. "I am anti-war. All the parties now recognise there is no military solution."

Then he takes to the podium to denounce what the Americans used to call a "war on terror". He vows to shoot down any US drones operating in tribal areas along the Afghan border.

The former cricket captain, known in the west as a charismatic playboy, also pledges to establish a model Islamic welfare state.

That message resonates in one of the most conservative parts of Pakistan.

Free laptops

The stage behind him is heaving with local politicians, hangers-on, and Pakistanis who have flown in, everywhere from Luxembourg to Australia, to be part of this moment.

Three young Pakistanis, just out of medical school, wait at the edge of the platform to get their pictures taken with their new hero. "We're voting for the first time," they tell me excitedly.

I point out they had been old enough to vote in the last elections in 2008.

"We weren't motivated then," explained 26-year-old Hammad Khan. "Even my grandmother is voting for the first time because of Imran Khan."

A decade ago, when Khan struggled to win any seats he was mocked: "Your supporters are all kids." He shot back then, "They'll be voting in 10-12 years." And so they are.

Nawaz Sharif insists he's also attracting some of that precious vote bank. Forty million young Pakistanis are now old enough to vote for the first time. His election rallies in Urdu are peppered with the English words "laptop" and "motorway". Building roads and distributing free laptops are his signature programmes.

But his favourite punch-line of all is: "I played cricket too, but it's not the only thing I've done."

At a packed gathering of shopkeepers in an Islamabad hotel, he adds, to rousing cheers: "I also made the atom bomb."

That goes down well in a country that hailed Pakistan's entry into the nuclear club when Nawaz Sharif was in power.

Now the nuclear state does battle with constant power-cuts crippling the economy, violence tearing the nation apart, and corruption eating into all parts of life.

Whoever wins this election also wins the hardest of jobs.