Why US looks set to continue Egypt funding - for now

- Published

- comments

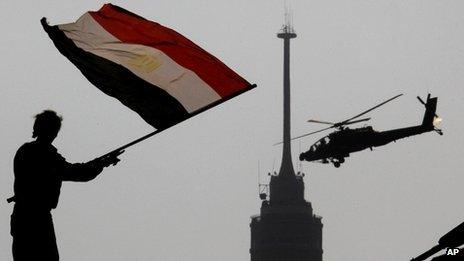

Most of Egypt's modern military equipment have been financed by a US assistance scheme

A decision by the United States to continue giving military aid to the Egyptian army would be a fork in the road moment in Middle East politics.

But despite President Barack Obama's early appeals for restraint and announcement that this military assistance was "under review", the signs in Washington are that this is precisely what he intends to do.

The acquiescence by Western countries to the Algerian army's coup of 1992, overthrowing an elected Islamist government, defined a generation of militants.

When the Bush administration, almost a decade later, put forward its ideas about spreading democracy in the region following 9/11, the-then secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, insisted that the power of popular votes was more important than the maintenance in power of American allies in the region.

Key Middle East ally

For 12 years the White House has extolled democracy even when its outcome often seemed to challenge US interests. Now it seems ready to acquiesce in the Egyptian army's ousting of President Mohammed Morsi and it is perhaps all the more remarkable that this shift should be happening under Mr Obama.

Engaging on background terms with Americans who have been instrumental in formulating recent Middle East policy it is apparent that they believe the assistance, valued at $1.3bn in 2010, should go on.

Turkey's Prime Minister Erdogan has lambasted the US and EU over their response to events in Egypt

When I asked one senior military type whether it should stop, the answer was: "No I do not think so, as this appears to be a pretty widely supported move by the [Egyptian] military."

Another former US government official suggested the White House approach of raising concerns while using the aid as leverage to insure a rapid return to an elected government was the right one.

Many in Washington evidently fear that a rapid severance would leave them without influence in that equation, one noting that the US has felt like "a bystander" in Egypt during the past year.

Among Middle East public the quantity and effect of US military aid tends to be over-estimated. Egypt's package has been in place since the 1981 peace agreement with Israel, and essentially it operates like a credit note which the Egyptian army can spend in the US on hardware.

Most of the modern Egyptian weapons' programmes from the F-16 fighter to M1 tank or Apache helicopter have been financed under this scheme.

The $1.3bn given annually in this form compares to $18bn pledged in financial aid by Arab neighbours - notably Qatar and Saudi Arabia - since the Egyptian revolution of 2011 or the country's $20bn annual bill for subsidising fuel and food.

Nevertheless the help given to the Egyptian generals has long created the impression of a Middle East strategic alliance second only in importance to that of the US with Israel.

Long review period

The bloodshed in Cairo on Friday though highlights the political risks for the Obama administration in continuing such a close relationship. There is a feeling among those who I contacted that they cannot give carte blanche for repression in Egypt, one noting, "I don't think we should terminate security assistance funds right away".

This then hints at a possibility that if there is increasing bloodshed, or a recognition after some months that the army's professed desire to hold new presidential and parliamentary elections as soon as possible cannot be relied upon, American policy may change. The US president's "review" could therefore be a long lasting affair.

That approach though does not mollify the strong feelings of this moment. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey lambasted the European Union and US on Friday, noting that events in Egypt were a "test of sincerity" for their professed support of democracy in the region, "and the West failed the class".

Assailed by popular protest, and in a country notorious for military interventions in politics, it is not hard to see why Mr Erdogan should be particularly sensitive on the topic. It is an odd thing though to see Egypt suspended from the African Union, but with the EU and US declining to call events in Egypt a coup d'état.

Until this week, anti-Morsi demonstrators had been accusing the US of backing the unpopular president. Now he has been deposed, it seems, that his Muslim Brotherhood supporters may also be angry with the US for sitting on its hands and providing more weapons to the Egyptian army.

Thus there are risks for the White House not only of abandoning the stated support for Middle East democracy of the past 12 years, but also of firing deep antagonism among broad swathes of Egyptians.