Destitution drives Syrian refugee children to work

- Published

Syrian refugee children on their way to work in vegetable fields in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley

The Syrian children stood at the side of the road just after first light, just as they were told.

At this ragged cluster of tents in the Bekaa Valley, they weren't waiting for a school bus in the early morning cold.

An open back truck arrives just after 06:00 to take them to the fields to help bring in the harvest.

Across this fertile land of eastern Lebanon, Syria's refugee children are increasingly doing the jobs of adult manual labourers.

"It's a worrying phenomenon we see increasing by the day." Unicef's regional director Maria Calivis told me. "The numbers of refugees are growing larger, and the people arriving are more destitute than ever."

Many families feel they have no choice but to send their children to work

On the streets of the Lebanese capital Beirut, refugee children can be seen selling trinkets or shining shoes to bring in some money to support their families. But organised child labour is a new and troubling problem that underscores Syria's deepening humanitarian crisis.

"The invisible is becoming visible," affirmed Ms Calivis.

Dozens of children dressed in plastic sandals and thin shirts or dresses shiver in the dawn chill. They cling to metal bars as they're thrown back and forth in the truck normally used to transport livestock which ferries them to a nearby farm where courgettes are ripe for picking.

This pint-sized gang of workers swarms into the lush green fields as the Syrian middleman, who organises the labour on this Lebanese farm, shouts at them to get to work.

"My hands hurt," confesses 14-year-old Abdul Aziz as he holds up his grimy hands and points to the prickly stalks. Even in his pain, he manages a shy smile.

In other fields, where children have been harvesting crops such as grapes or potatoes, the work is even more difficult, and dangerous.

Aid officials told me of seeing children cut themselves with knives or run in fear from powerful combine harvesters that churn the soil.

Hard at work picking courgettes

"It's a bad situation," says Tarek Mazloum of the Lebanese charity Beyond as he watches little children struggle with big buckets of fat green courgettes.

"Each family consists of six, seven or eight children and all of them work, from three or four years old," he explains. His charity helps provide for Syrian refugee families.

He shakes his head, visibly upset. "But we can't stop it. If the children don't work, the family would be destroyed. They wouldn't eat."

"It is up to all of us to find a solution," says Unicef's Maria Calivis. "Children should be at school and not at work."

But when Lebanon's public schools opened this week, there simply wasn't enough space for all the young Syrians.

UN officials say there are now about 400,000 Syrians of school age but only 100,000 extra places.

The UN, working with other aid agencies, has launched a "Back to Learning" campaign which provides for informal education so children don't fall too far behind.

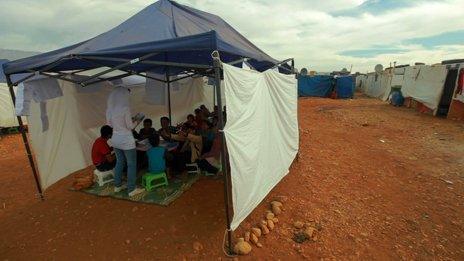

On our visit to the Bekaa Valley the children finished their work in the fields and then were taken back to their settlement where they helped pitch tents on rocky ground, and arranged brightly coloured plastic tables and chairs for a makeshift open air school.

Syrian refugee children are taught in makeshift schools

Abdul Aziz, who hours earlier had showed me his hurting hands, was now enthusiastically clapping with other children in a loud rendition of "one, two buckle my shoe".

Classes like this are not just to forget the pain of the morning, but the even greater trauma families escaped in Syria.

"We try to help them forget the past," says the lively young teacher Azza who is also a refugee from the Syrian city of Homs. "We try to give them a time of happiness, of fun."

"I like going to school," says 10-year-old Rasha whose family fled the northern city of Aleppo several months ago. "Its better in Lebanon - there are no bombs here," she tells me with a fetching smile as she clasps her hands decorated with bright blue nail polish.

Home for these children is now tents fashioned from rough tarpaulin and thick sheets from advertising hoardings. The land is rented from local Lebanese landlords, often through Syrian labourers who've been living in these kind of informal settlements for years. Lebanon, unlike Jordan and Turkey, has not authorised the UN to establish formal refugee camps.

The Syrian refugee population in Lebanon is growing by the day

Rasha now lives with her five siblings and her widowed mother Fatima in a rectangular blue tent just behind the cluster of classrooms.

She and her brother Omar both work in the fields. "I feel like my heart is being ripped out," her mother Fatima laments, fighting back tears. "But what can I do? If my children don't work, we can't live."

In the back of their tent, two young cousins who just arrived from Syria the night before sit listening quietly. It's a visible reminder that the refugee population keeps growing by the day, and so does the problem of child labour.

"We are following up with NGOs to ensure the work is not exploitative or hazardous," says Unicef's Maria Calivis. "We have also started a campaign to ensure parents are aware this is not the best thing for kids."

Another answer, suggest aid officials, would be financial vouchers for families but at the moment that is a costly, and difficult, option that isn't in anyone's budget.

"This is a really big dilemma for us," says Soha Boustani, Unicef's communications chief in Lebanon. "We want to protect these children and at the same time we don't want to deprive the family from their only source of income."

For now, there are no easy answers to stop child labour, or to end Syria's punishing war. Both are destroying Syria's future.