UN sounds dire warnings over 'trapped' Syrians

- Published

Lyse Doucet: "Food has become a weapon of war"

More dire warnings have been sounded on Syria's deepening humanitarian crisis.

"Hundreds of thousands, a million, maybe two million, are near starvation or actually starving," declared UN envoy Lakhdar Brahimi at a press conference in Geneva on the upcoming Geneva 2 talks.

His call for urgent access to areas across Syria now cut off by government troops in some areas, and rebel forces in others, was echoed by an alarm bell in one specific area.

"It is my responsibility to inform the international community that humanitarian conditions in the besieged refugee camp of Yarmouk are worsening dramatically and that we are currently unable to help those trapped inside," said the director general of UNRWA, Filipo Grandi, in a statement.

"If this situation is not addressed urgently, it may be too late to save the lives of thousands of people including children," cautioned the official who heads the UN agency responsible for Palestinian refugees.

Pictures recently obtained by the BBC from inside Yarmouk showed street markets with only radishes for sale. Aid officials have been expressing concern for months about growing malnutrition.

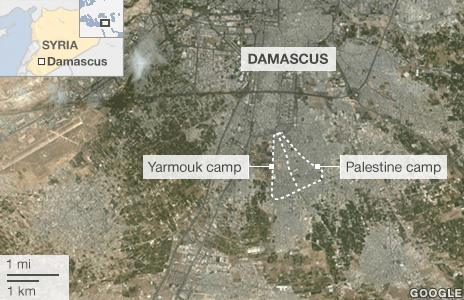

Yarmouk, a southern suburb of Damascus, was once home to Syria's largest population of Palestinian refugees but since the conflict began most have fled. A community of 160,000-180,000 now numbers around 20,000 or less.

Aid officials in Damascus recently told me "the gates of Yarmouk" were slammed shut in July and almost no aid has been allowed to enter since then.

The statement by Mr Grandi highlighted: "The continued presence of armed groups that entered the area at the end of 2012 and its closure by government forces (that) have thwarted all our humanitarian efforts".

Cut off

Yarmouk's situation is complicated by rivalries between Palestinian and Syrian armed groups.

The Syrian government recently authorised limited operations to distribute food rations and medical supplies but the process was soon halted by violence.

Yarmouk is only one of many enclaves paying a painful price in a punishing war.

A confidential UN document leaked to the BBC shows that more than a quarter of a million Syrians are now living in areas, mainly in the Damascus suburbs, cut off by government troops.

About 45,000 people, mainly in the north, are besieged by rebel forces.

The situation keeps shifting on the ground but this document says 2.5 million Syrians are stuck in "besieged or hard to access areas".

'Shameful'

There's deep frustration in the aid community that a world which came together to deal with Syria's chemical weapons arsenal cannot do the same when it comes to tackling a deepening humanitarian crisis.

"I have never seen a humanitarian crisis on this scale which does not have a Security Council resolution," one aid official recently told me. "Its absolutely shameful," the official said.

The absence of action reflects the deep political splits in the international community over Syria.

A few months ago, Russia agreed to what's known as a presidential statement, a non-enforceable Security Council request, which called on the Syrian government to improve aid distribution.

And the UN's humanitarian envoy Valerie Amos recently brought together an informal "high level group on Syria", to explore ways to ease this suffering of civilians. The group includes the five permanent members of the Security Council as well as regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Starving an area is a war crime. In Syria, food is a weapon of war used by all sides as they try to gain ground militarily.

But, this week in Damascus, we heard new commitments being expressed, on all sides, to do more to protect civilians.

Promises

A statement issued by rebel commanders operating across Damascus suburbs pledged to protect aid convoys and guarantee distribution to civilians.

Both the Minister of Social Affairs, Kinda al-Shamat, and Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad told the BBC there would be "more access, more cooperation".

Aid agencies say more visas are now being approved to bring in more staff to carry out humanitarian work but the numbers still fall short of what is needed. And, in some areas, aid convoys have been able to cross between rebel and government controlled areas.

The government's new promises come in the wake of its recent military advances on the outskirts of Damascus.

"Aid follows the military," reflected an aid official who expressed scepticism about the new pledges.

Would the government only allow aid into those areas where its forces had prevailed?

"I can assure you it will go to all Syrians who are in need," Dr Mekdad told me.

This latest UN warnings will test these promises from all sides.