What was achieved at Montreux talks?

- Published

By the time a warm winter sun sank in the still blue waters of Lake Geneva, Montreux's moment in the annals of Syria's devastating war also came to an end.

The quaint, quiet charm of this Swiss town was a stark contrast to the invective that marked the start of an embattled process of negotiations known as Geneva ll.

And yet, "better than expected" was the verdict of an official closely involved in preparations for this historic gathering.

Of course, expectations were so low such that just showing up was progress, after months of delays, discord and doubts.

But "either Syrian side could have walked out but didn't", was the remark uttered by many observers.

As they sat around a vast U-shaped table with foreign ministers and envoys from more than 40 countries, their mutual contempt was contained in an acrimonious blame game for Syria's bloody war.

"It is not easy to sit across the table after so much bloodshed and destruction," was how UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon summed up the day.

Opening salvo

And now both sides are showing a readiness to at least put a toe in the murky waters of negotiations that officially start in Geneva on Friday.

Syria's Foreign Minister, Walid Muallem

Will the mood be better, or worse, once the world's television cameras are no longer in the room?

"Depends," was the tentative reply of a member of the Syrian government delegation who said their team had resolved to be "quiet and constructive". Never mind that the opening salvo of Syria's Foreign Minister Walid Muallem was anything but.

The spokesman for the opposition coalition Monzer Akbik told me they would be "responsible, serious and positive". But, he added, "if it becomes clear talks are hopeless, there is no point in staying".

Syrian presidential adviser Dr Bouthaina Shaaban said they would be talking "through the United Nations, through Lakhdar Brahimi". Her remarks suggest the first round would start as close proximity, not direct talks, with Mr Brahimi shuttling between rooms.

At a press conference on Wednesday evening Mr Brahimi said: "Do we go straight to meet in one room on Friday or do we talk some more? I don't know yet."

He also admitted there was: "no illusion that it is going to be easy but we are going to try very hard."

Mediating role

In the run-up to these talks, Mr Brahimi told me he wanted to deploy a format similar to one he used in the Afghan Bonn talks in late 2001 which established an interim government to replace the Taliban.

Lakhdar Brahimi (L) and Ban Ki-moon

Only Syrians would sit at the table, with Mr Brahimi playing a mediating role. Outside delegations would be available in rooms nearby. Diplomats from the US, UK, Russia and other key players are expected to be in the vicinity for these Syria talks.

"First, we will discuss a schedule for the talks which is very important," explained Monzer Akbik.

But most important is to discuss what Geneva ll is all about. The Geneva l document talks about the formation of a transitional governing body formed by "mutual consent". For the opposition, this means, by definition, there is no role for President Assad.

For both sides, his role is a rigid red line.

"This is not about power," Dr Shaaban told me. "This is about Syria, the future and welfare of its people."

A concerted push by Damascus to turn these talks into a focus on terrorism, and the growing threat posed by al-Qaeda-linked Islamist groups, did not succeed.

Ban Ki-moon referred to his conversations with Syria's foreign minister and said: "I told him fighting terrorism is important but you have to deal with this with a political solution."

Brutal battles

Other issues will be on the table including aid corridors to tackle what is now deemed the worst humanitarian crisis of our time.

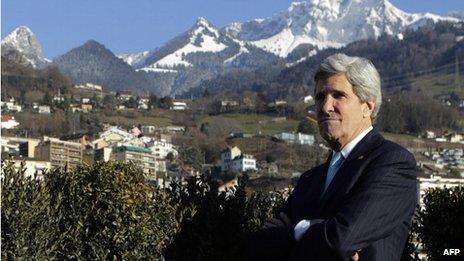

John Kerry poses outside the meeting room in Montreux

But this new focus on talks isn't the only game in town. US Secretary of State John Kerry put it this way: " I will just say to you that lots of different avenues will be pursued, including continued support to the opposition and augmented support to the opposition."

On the ground, more brutal battles for power will continue and are likely to intensify. Major opposition forces speak with derision about the Geneva ll process taking place far away in five-star hotels.

And Syria will step up its diplomatic drive to sell its narrative to the West. Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad recently told me that, after a start to Geneva ll, he expected more embassies to quietly send some of their diplomats back to Damascus to strengthen their presence there.

In Montreux, a small but significant symbolic step was taken. A taboo was broken - bitter rivals sat in the same room.

As the Montreux press centre was closing for the night, Syrian government officials and activists lingered in the same hall, mingling in different corners.

"Certainty is a very rare commodity in our kind of business," remarked Mr Brahimi just before he left Montreux for Geneva where the real work is just starting.