Nato's Anders Fogh Rasmussen sees power slipping away

- Published

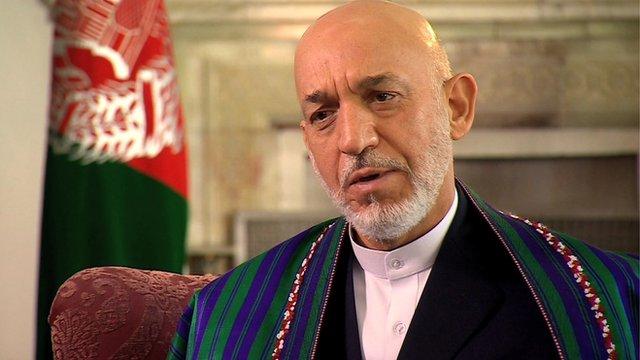

Anders Fogh Rasmussen: "To go to the bottom line, I don't think President Karzai will sign"

There is an unmistakeable sense among Western decision-makers of power slipping away.

It's not an argument about American abstention or decline, although that plays into it for some critics of the Obama administration.

It is more to do with the exhaustion - moral, political and economic - of nations that have been in the forefront of the international security business, and the vibrant ascendancy of some other players.

Talking on Monday to Anders Fogh Rasmussen, secretary general of Nato, he can see the reasons for austerity, for cutbacks in government spending in order to reduce deficits, but he can also see its likely results.

"It means," he says, "we will have less influence on the international scene. The vacuum will be filled by other powers and they do not necessarily share our interests and our values."

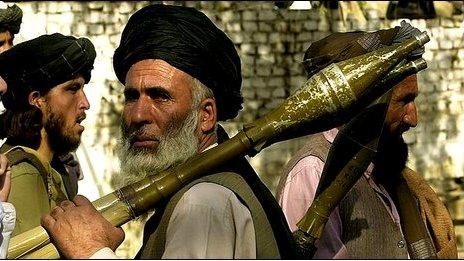

Many Britons or Americans still fuming at the destruction wrought in Iraq or Afghanistan may find a loss of influence preferable to a repetition of the past decade's adventurism, but it troubles many diplomats, soldiers and politicians deeply.

Indian nuclear submarines

General Sir Nick Houghton, the UK's chief of defence staff, said a couple of months ago that he had come to the "stark conclusion" that one of his biggest professional challenges "is to help re-validate the utility of the military instrument of national power in the minds of the government and the wider public".

It might be argued that a rejection of force by Western countries is a temporary phenomenon following the losses of two difficult foreign wars, and an economic downturn that has forced an emphasis on cutting deficits.

But the reduction of spending by Nato countries is just one aspect of this power shift - indeed it is the lesser aspect of it compared with the increases in military spending by countries like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

In a survey to be published on Tuesday by the analytical company IHS Janes, it is estimated that defence spending by non-Nato countries will outstrip the Western alliance by 2021. The figures show that Saudi defence spending has tripled in the past decade and that China's spending will by next year outstrip that of the UK, France, and Germany combined.

Similar patterns emerge in the annual surveys of think tanks such as the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) and the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, which will publish its annual round up of world military standings later this week.

Last year, Hamid Karzai accused Nato of having caused great suffering in Afghanistan

The SIPRI data, which lags one year behind, shows that Russian arms sales increased markedly, by 28%, in 2012, and that much of this was attributable to increases in domestic defence spending. Western arms sales declined during 2012.

Along with the hardware comes all manner of indications of qualitative shifts in hard power. India is now launching its own spy satellites as well as nuclear submarines. The United Arab Emirates, long flush with cash but short of people to expand its armed forces, has recently announced that it will introduce national service to bulk up the ranks.

Somali pirates

Is growing spending by these economically powerful countries a zero-sum game? Does it have to rebound to the detriment of the West? Many feel that the erosion of US primacy in places like the United Nations Security Council may be a good thing, particularly if newly confident emerging powers are willing to share the burdens of international operations - as China has by sending frigates to counter Somali pirates.

It is, however, in the sensitive area of "interests and values" that Mr Rasmussen suggested that the concerns of many Western "securocrats'" now centre.

Russia and China, for example, have long stressed the need to respect the right of countries to deal with their own internal problems, rejecting internationally mandated intervention.

For those who believe in the ideas of humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect, the fate of Syria marks a grim portent of what these changes in the global realities of power might mean.

- Published30 January 2014

- Published16 January 2014

- Published7 October 2013