Syrian peace talks: Small steps forward, big lurches backwards

- Published

The UN estimates about a quarter of a million Syrians are in desperate need in besieged or hard to reach areas

"If peace cannot be brought, how can humanity be brought to the conduct of the war?"

That's how David Miliband, who heads the International Rescue Committee, recently phrased two pressing goals for Syria.

On Monday, as a second round of peace talks gets under way in Geneva, both the worsening war and a grave humanitarian crisis will be on the agenda again.

For much of the first round, UN envoy Lakhdar Brahimi expressed anguish over the failure of warring sides to agree, at the very least, a humanitarian ceasefire in the embattled city of Homs.

Then, a few days after talks broke up, the UN announced a "humanitarian pause" had finally been reached between government and opposition forces.

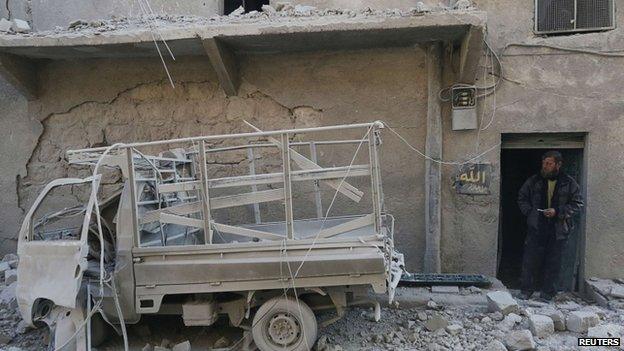

Over the past three days, a temporary truce allowed more than 600 women, children and the elderly to escape the ruins of a shattered Old City which has been in rebel hands, under siege by government forces, for nearly two years.

Young men who left the area were taken in for questioning by Syrian forces. Their fate is still not clear.

But the joint aid convoy of the UN and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent Society (SARC) still came under mortar and gunfire when it entered the area with food and medicine to ease the suffering of starving people. More than 15 aid workers were pinned down, unable to exit, for hours.

"All the devils in this crisis will always try to hinder our work," regretted SARC's head of operations Khaled Erksoussi, on a telephone line from Damascus with a voice tinged with exhaustion and anger.

A temporary truce has allowed more than 600 women, children, and the elderly to escape the ruins of Homs

The joint aid convoy of the UN and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent Society (SARC) to Homs came under mortar and gunfire

"We have to be stubborn and not lose hope about getting aid to the people in need," he emphasised.

Badly needed food distribution has also started in the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk in Damascus which has been cut off for many months. But Christopher Gunness, spokesman for the UN's Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) said the operation has had to be suspended because of clashes close to the distribution area.

Such is the sad reality of the existential battle in Syria. Everything - even daily bread and innocent children - are weapons in this war.

If there are, to use Mr Erksoussi's phrase, "devils in this crisis", there are also few angels. All sides are putting civilian populations in harm's way to press for advantage on the battlefield.

There are still many more places and people who urgently need aid - such as Deir al-Zor in eastern Syria

Videos and eyewitness accounts point to attacks by pro-government forces in the latest violence in Homs but Syrian officials put the blame on "terrorists" and infighting among rebel forces.

There is still no recognition on the ground of that mantra repeated endlessly outside Syria that "there is no military solution to this crisis".

That is what makes the prospects for success in the Geneva talks still so slim.

Like these aid operations, negotiations will be a tortuous process of small steps forward, and big lurches backward.

"Its very good that it is taking place but I am sad to report there is no progress," admitted a grim-faced Mr Brahimi at the Munich Security Conference only hours after the first round ended in Geneva.

"It's not often that you hear diplomats being so honest about failure," remarked one observer in the audience. He then added, only partly in jest: " You have to admit there is a certain quality to it."

When the stakes are so high, and the damage in Syria so deep, there is no purpose in pretending the reality is any different.

And yet, the talks were not for naught. Two warring sides, who speak only with contempt of each other, occasionally sat in the same room that week. Much of the "talks" was talking past each other, or through Mr Brahimi.

But the hope is that, over time, individuals will start listening to a starkly different narrative of the war coming from their enemy.

No-one expects progress to be made any time soon on the main overarching goal in this process - the establishment of a "transitional governing body" set out in the "Geneva I" document, external that underpins the negotiations.

Syrian government officials declare that President Bashar al-Assad is there to stay unless elections or a referendum decide otherwise. The opposition insists there can be no future for Syria that includes him.

All sides are putting civilian populations in harm's way to press for advantage on the battlefield

In the meantime, pressure mounts for progress on the other goal that is not formally part of this process . To use David Miliband's phrase, it is how to bring "humanity to the conduct of the war".

A new global coalition of aid agencies and human rights groups is taking shape to give louder voice to demands for local ceasefires, aid corridors, and a United Nations Security Council resolution on humanitarian issues alone.

In recent months, under pressure from allies and aid officials, the Syrian government has been giving more visas to aid workers and has agreed to limited access in some besieged areas.

But there are still many more places and people who urgently need aid. The UN estimates about a quarter of a million Syrians are in desperate need in besieged or hard to reach areas.

Syria's humanitarian crisis needs, most of all, a political solution. The two goals are inextricably linked.

Peace is the ultimate prize. But, when so many are starving, even the arrival of bread counts as progress in peace talks.