Kabul ushers in uncertain New Year

- Published

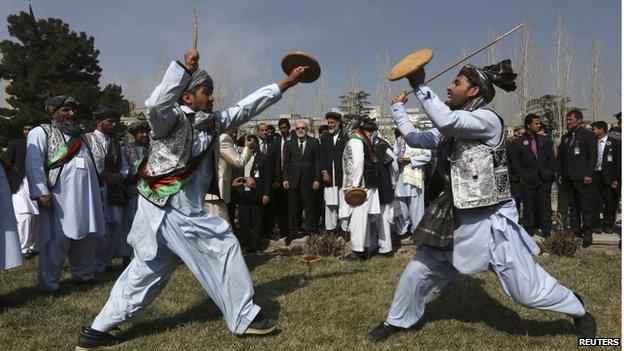

Performers from across the region congregated in Kabul for this year's International Nawroz Festival

Kabul's Salaam Khana was once a stately palace where kings were crowned and Afghans gathered to salute their royal ruler.

This week it set the stage for a new chapter in Afghanistan's chequered history.

"We have broken the silence," marvelled Dr Ahmad Naser Sarmast, founder and director of Afghanistan's National Institute of Music.

"After 30 years, a new generation of Afghan musicians is playing music here," he exclaimed before he took to the stage to conduct a specially composed song to mark the start of the Persian New Year, known as Nawroz.

There were no kings in this audience to appreciate the uplifting melody and verse. But four Presidents, and senior officials from a dozen countries, along with Afghan dignitaries and diplomats, packed the elegant hall for the International Nawroz Festival.

The annual event is a celebration, recognised by UNESCO, of the ancient rituals which coincide with the start of spring.

Iran's reformist President Hassan Rouhani hailed this year's Nawroz as a "festival of moderation," celebrating the mild climate of Spring - a time for policies of "prudent moderation," he said.

Colour, sound and the smell of food filled the air outside the Presidential Palace

Despite the fortress security, the venue was transformed by the culture on display

Tajik traditional musicians performed alongside Afghan tribal dancers and many others at the festival

"We have broken the silence" said Dr Ahmad Naser Sarmast of Afghanistan's National Institute of Music

He expressed hope that Afghanistan's presidential elections, set for 5 April, would usher in "peace and progress… another gift of Nawroz."

Afghanistan's President Karzai emphasised that "the future of our land depends on regional integration and cooperation."

At the last event in Turkmenistan last year, the Afghan leader confidently announced that his country would be next to host this special gathering.

With only months to go before he leaves power, it may also be one of his last opportunities to officially welcome his neighbours to the fortress where he has lived and worked since the fall of Taliban in late 2001.

Runner-up venue

But he had not originally planned to host them in those familiar surroundings.

Despite months of effort, and millions of dollars spent, the chosen site of Paghman Hill, about an hour's drive from Kabul, wasn't ready in time. Roads had been paved, but the grand Palace being built close to the historic site where Afghanistan declared its independence in 1919, was not complete.

"We can fight against anything, but not against nature," explained Farouq Wardak, the education minister charged with organising the festival, who told me rainfall had slowed the pace of construction.

President Karzai is said to have personally inspected the grounds and declared them unfit to welcome guests, which included the Presidents of Pakistan, Iran and Tajikistan.

But a worrying surge in Taliban attacks must have concentrated minds too. The year has barely begun and already 50 people have been killed in violence, including nine - Afghans and foreigners - who lost their lives when Kabul's five-star Serena Hotel came under fire.

"We are not worried about Taliban attacks," Mr Wardak declared with bravado. "We want to demonstrate to the world that on one side there is war and destruction, on the other there is construction and development."

And despite being the second-choice location, the sprawling grounds of Kabul's "Arg" or Citadel compound, encircled by rings of concrete and steel, were transformed into a festive open air carnival. Invited guests, all carefully screened, strolled across manicured lawns dotted with bright national flags.

It was a lively landscape of Turkmen musicians' white marshmallow-shaped hats, twirling Afghan tribal dancers' sparkling vests, and the embroidered waistcoats of many nations' performers, plucking traditional instruments.

Along one high thick wall edged with razor wire, kebabs sizzled, huge vats of rice and meat were stirred, and rounds of steaming bread emerged from clay ovens.

Western Kabul's Sakhi shrine is a traditional place of prayer at the New Year

The festival is often celebrated with food, cultural events and new items of clothing

Uncertain times

But the New Year, which officially began on 21 March wasn't just welcomed inside palace walls.

In the west of Kabul, the magnificent blue-tiled Sakhi shrine, in the foothills of Koh-e Asmai, is a traditional place of prayer at the start of the year. Afghans often bring their worries and wishes here.

"What did you wish for?" I asked one woman veiled in black who hurried by. "I wish for a peaceful year," she said. "I'm worried the elections could be bloody".

"I'm preparing for my exam," a university student remarked." I hope Afghanistan will pass its own test this year, just as I will pass mine."

Outside the shrine, families lingered around shops selling stacks of bright bangles, painted Nawroz tambourines, and snacks of all kinds.

Today was a day of new colours and new sounds, marking the start of a momentous year, when Afghans will again confront the problems of the past.

"I think the elections and spring are both very symbolic," remarked Dr Sarmast of Kabul's National Institute of Music. "Both mean the beginning of life, a new step of development."

Landmark elections will test the nation's resolve this year, as will the departure of foreign combat troops.

Facing deeply uncertain times, Afghans did what they could to try to get the year off to a good start.