Gaddafi's legacy continues to haunt Libya

- Published

Benghazi has been at the centre of unrest since the fall of Gaddafi

The partial ceasefire announced by the Libyan army on Sunday, following peace talks with various factions in Geneva, is the first good news to come out of Libya for months.

But even if the ceasefire holds and the peace talks bear fruit, there is a long, long way to go before the chaos there can be sorted out.

Libya is a deeply disturbing country at present.

It has all the signs of a failed state.

Under Colonel Gaddafi, Libya was a scared, unnaturally poor country whose huge oil wealth had been squandered by its leaders.

But at least it was peaceful. As a Westerner, you were perfectly safe there.

Hopes for peace

"The ghost of Muammar Gaddafi will always haunt us." In the lobby of a five-star hotel in Tripoli, a Libyan friend of mine who had worked closely with Gaddafi spoke the words softly to me.

Within a matter of weeks Gaddafi was dead, external.

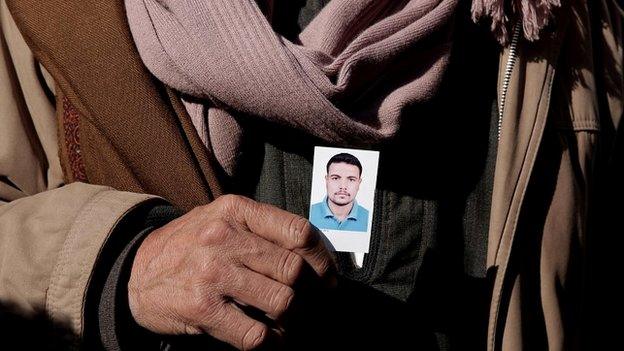

Opposition militias have battled for control of Benghazi

Now, said people like my friend, we can build a decent country again.

That was more than three years ago.

On the face of it, Gaddafi has already been forgotten.

The bullet-splattered images of his absurdly smiling face on concrete display-boards at major crossroads throughout the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahuriyah have disappeared.

The SPLAJ is history.

Gaddafi was ludicrous, utterly corrupt and personally degenerate; though Tony Blair, for Britain, and Nicolas Sarkozy, for France, were among those who were prepared to ignore all this and cosy up to him for the sake of Libya's oil wealth.

But Gaddafi had ruled the country in his addled way for more than 40 years, and had deeply affected the life of every single Libyan throughout that time.

You don't just kill a dictator like that, destroy his portraits, and put him behind you.

At first, after the overthrow of Gaddafi, there was political upheaval and some violence.

The hostility of provincial areas like Zintan, Misurata and Benghazi towards Tripoli was worrying, but it seemed reasonable to hope that things would settle down.

In July 2012, elections were held. They weren't altogether smooth, but there was a clear result: the moderate National Forces Alliance won almost half the seats. A government was formed.

But the armed groups which had fought the Gaddafi loyalists in the civil war hadn't gone away.

Their roadblocks made driving round Libya hazardous, and when they clashed there was trouble. Extremism was on the rise.

Ambassador murdered

On 11 September 2012 - the date was significant - Christopher Stevens, the American ambassador to Libya was murdered, external, together with three others, at the US mission in Benghazi.

Although the Islamic extremist group, Ansar al-Sharia, avoided claiming sole responsibility, vehicles with Ansar's logo on them were spotted at the mission during the attack.

Gaddafi dominated Libya for more than four decades

Last June, American special forces captured a leading figure in Ansar, Ahmad Abu Khattala (who had denied being involved), and took him to the US for trial.

In the wake of the attack on the US mission, big demonstrations in Benghazi demanded an end to the actions of the militias, and Ansar's headquarters were stormed and ransacked.

But it didn't stop Ansar in the long run.

Last July, it took complete control, external of Benghazi, and has a strong presence in the eastern town of Derna, external.

Islamist front-line

Libya is not only violent and deeply divided, therefore; it has become another front line in the battle between extreme Islamism and the rest of the world.

This certainly wasn't the outcome Nato expected when Britain and France started bombing Gaddafi's forces in 2011.

So were they wrong to get involved?

The French and British air forces intervened to protect the largely unarmed insurgents of Benghazi from the advance of Gaddafi's tanks.

If the tanks had re-conquered Benghazi, Gaddafi might still be in power, and Libya would be a quieter place.

But Gaddafi's rule, which lasted 42 years, was certain to collapse at some point.

In that way it was similar to Saddam Hussein's Iraq.

The choice wasn't between the continuation of a quiet, safe, if unpleasant regime and the chaos that exists today; it was a question of when the system fell, and whether the aftermath could be controlled.

Depressingly, Libya may still have plenty of violence to go through before it can become peaceful again: assuming it doesn't break up into three or four mutually hostile parts.

In Iraq, you often hear people say they wish Saddam was still in power.

That instinct is rarer in Libya, but it certainly exists.

It is Gaddafi's revenge on the people who overthrew him.

Correction 19:44 20 January 2015:

This piece has been amended to correct a number of errors about flights and transport links to Libya, and remove an incorrect reference to foreigners requiring the assistance of armed groups to travel around the country.

It also incorrectly stated that Ansar al-Sharia formally gave its allegiance to IS.

- Published19 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published3 January 2015