Should animals have the same rights as humans?

- Published

A New York court will resume hearing a case this week about the possible illegal detention of two chimps at a university lab.

Lawyers acting for the chimps, Leo and Hercules, want them to be moved to an animal sanctuary. Researchers at Stony Brook University are using the chimps for research on physical movement.

In a potentially significant ruling Judge Barbara Jaffe at one stage suggested the chimps had the right of habeas corpus - the ancient legal principle under which the state has an obligation to produce missing individuals before a court.

But having initially used the words "habeas corpus", the judge subsequently struck them out, external, suggesting the court does not consider the animals to be legal persons.

Hercules and Leo's lawyers say they are not too dispirited as the court is still asking the university to justify why they are holding the chimps.

The case follows another ruling in New York last year, where a judge said a chimp was not entitled to the same rights as people.

'Speciesism'

The idea that animals could be considered legal persons with rights is relatively new.

But in centuries past animals were quite frequently involved in court cases in which they were put on trial. Most were found guilty of offences such as murder and assault. Punishments included the hanging of animals found guilty.

Opponents of the concept of animal rights argue that since animals have neither a sense of morality nor an understanding of their duties towards others, they can't have rights. Others, in turn, dismiss such views as "speciesist".

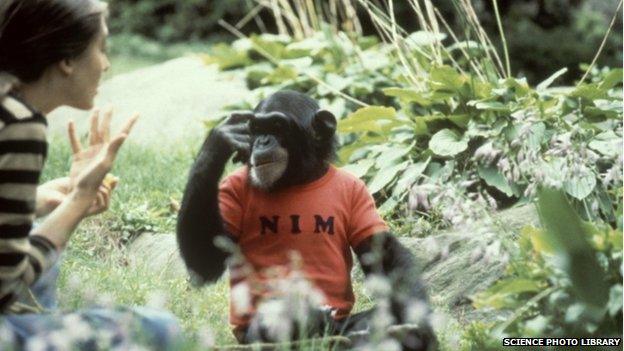

Attempts to understand the nature of animal behaviour have sometimes taken the form of highly unusual experiments. In one case a chimp called Nim was brought up with a New York family.

Project Nim, a documentary following the life of Nim the chimp, was released in 2011

The chimp's full name, Nim Chimpsky, was a play on words. The philosopher Noam Chomsky had argued that animals do not have an innate understanding of grammar and that humans are uniquely hardwired to comprehend language.

The family raising Nim hoped to prove that the chimp in their midst would be capable of grammatically structured sign language. The experiment also focused on Nim's sense of morality.

New Yorker Jenny Lee was 13 years old when Nim, then an infant chimp, was introduced to her family and became her "brother". She believes that even if Nim could not be persuaded to stop biting people, he did display some behaviours that seemed quite human.

"He quickly understood how to say sorry and when sorry was appropriate," Ms Lee told Newshour Extra. "He would very delicately kiss the tears off my cheek."

Animal cases through time

1266: In the earliest extant record of an animal trial - a pig was executed in Fontenay-aux-Roses, external

1654: English Civil War leader Oliver Cromwell bans cockfighting, dog fighting, bull baiting and bull running. The law was later overturned

1981: The first US conviction for animal abuse against an experimental laboratory is achieved, external, after an undercover investigation by animal rights activists

1992: Switzerland amends its constitution to recognise animals as beings and not things

1993: Release of The Hour of the Pig. The film, set in 15th Century France, depicts the life of lawyer Bartholomew Chassenee who represented animals accused of crimes

1999: New Zealand grants basic rights to five great ape species, banning their use in research, testing or teaching. This is considered the greatest legal success in the history of animal rights

2002: Germany amends its constitution to guarantee rights for animals, external, becoming the first EU country to do so

2015: A New York court considers whether chimps are legal persons

Human moral code

But animal rights sceptics believe that even if Nim had some humanlike characteristics and some basic communications skills that does not justify blurring the lines between humans and other animals.

"We have to put into different categories, ourselves - humanity that is - and the rest of the living world," says the leading British neurobiologist, Prof Sir Colin Blakemore.

Prof Carl Cohen of the University of Michigan, Anne Arbor shares that view. Animals, he argues, do not know anything about morality: "Animals do not commit crimes, animals are not attacked for their moral views. Rights are a concept special to the human moral code," he says.

While humans have an obligation not to cause animals needless suffering, he argues, that does not mean animals have rights, as the concept is alien to them.

Utilitarian argument

Not all of those seeking to protect animals rely on rights arguments.

Others argue on the basis of utilitarian calculations of maximising happiness and reducing misery. Factors to consider would include the degree of an animal's autonomy, sensitivity to pain, level of sentience, self-awareness and ability to hold preferences.

Undermining a chimp's autonomy, for example, could be taken as increasing its misery. The greater an animal's capacities, the more misery it would experience.

In terms of intelligence and emotional complexity chimps, the argument goes, have more in common with humans than they do with snails. It is a line of reasoning that offers relatively little protection to animals with fewer capacities.

Some argue that predation should be stopped, to prevent zebras being eaten by lions, for instance

Weakening the distinctions and blurring the lines between humans and animals could have grave implications for humans.

If a healthy chimp, for example, has greater autonomy than a human with dementia then might there be an obligation to look after the chimp ahead of the human?

Advocates of animal liberation have also argued that differing sensitivities to pain might be another relevant consideration in establishing what interests animals have.

Some have even suggested that there may be a case for stopping predation. In other words it might be morally necessary to prevent a zebra living in the wild from being torn to shreds by a lion.

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

- Published21 April 2015

- Published4 December 2014