The arrogance of power

- Published

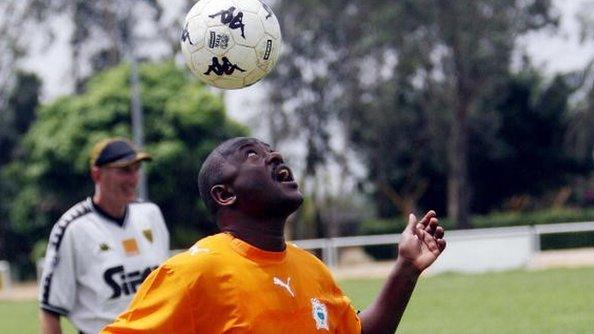

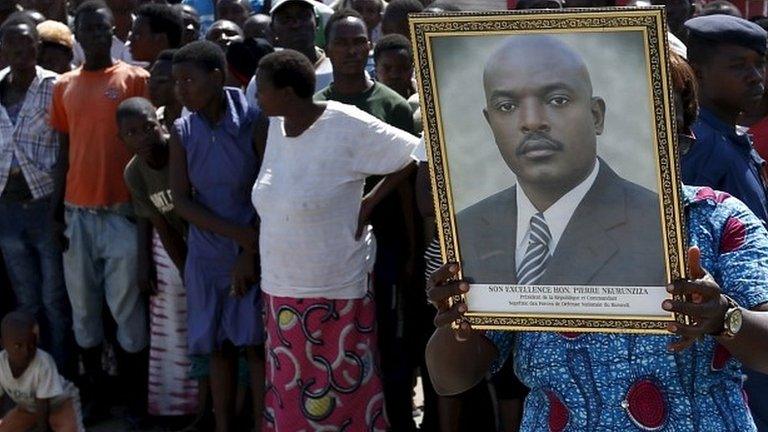

Pierre Nkurunziza is running in Burundi's presidential election which is scheduled for 15 July.

All over the world there are some leaders who are reluctant to give up power.

The most striking current example is Burundi's President Pierre Nkurunziza who, amidst violent opposition, is campaigning for a third term in office despite the constitution saying he can only have two.

He argues that he was appointed, not elected, to his first term so it doesn't count.

Many believe President Paul Kagame in neighbouring Rwanda is also looking to breach his two-term limit.

But that would be a mere dot in time for President Yahya Jammeh of The Gambia. "If I have to rule this country for one billion years I will," he told the BBC in 2011.

Hanging on does not always work.

The President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaore, was overthrown by popular protest last year for trying to change the constitution so that he could seek re-election.

'Let him continue'

While some presidents attempt legalistic tactics to get around term limits, others reject them outright.

Seven-term leader President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe says they are undemocratic: "We put a rope around our necks and say leaders can only have two terms," he told a summit of African Union leaders earlier this year, external.

"It is a democracy. If people want a leader to continue, let him continue."

Some post-independence leaders in East Asia have been equally unapologetic about staying in office for decades.

Indonesia's President Sukarno had 22 years at the top, while Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew was Prime Minister from 1959 to 1990.

"Lee Kuan Yew was an exceptional guy and at the end of his reign Singapore's GDP was over a dozen times higher than when he took over," Prof Kishore Mahbubani from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore told Newshour Extra.

"You have to look at it country by country and not assume there is one Western rule for the whole world."

Western idea?

Term limits are seen as a Western idea, in large part because of the United States' two-term presidential rule.

It was introduced as the 22nd Constitutional amendment in 1951, six years after Franklin Delano Roosevelt won his fourth term in office.

Before FDR the two-term idea was merely a convention dating back to the example of George Washington.

Franklin D Roosevelt at his inauguration for a fourth term as US president in 1945

Although the history of term limits can be traced back to ancient Greece, it is far from clear the idea is in fact a uniquely Western one.

Some European countries have no term limits, including the UK, Italy and Switzerland.

And elsewhere there is considerable support for a set period in office.

"If you look at the public opinion data we have on most African countries, a majority of people in Africa support presidential term limits," says Prof Nic Cheeseman of Oxford University.

"This isn't simply something being pushed by the West."

Hubris syndrome

Some argue for term limits on the grounds that a prolonged period at the top can change a leader's personality and damage his or her judgement.

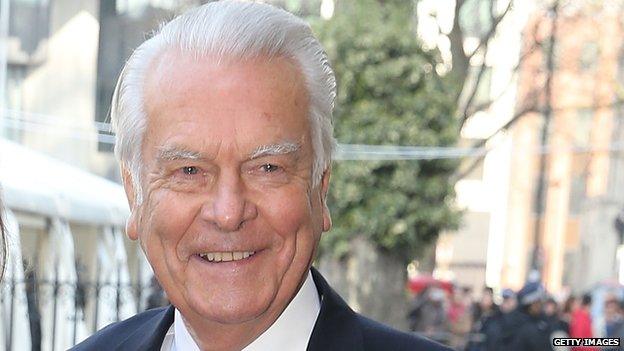

Former British foreign secretary and trained psychiatrist, Lord Owen, argues that by the time they have been in power for many years, some leaders tend to become arrogant, unwilling to listen and overly optimistic that their decisions will produce good results.

"Eight years is enough," Lord Owen told Newshour Extra.

"Blair is the classic example of hubris and it had profound effects because he reinforced the hubris of Bush and Bush reinforced Blair's and these two made terrible mistakes."

Lord Owen led the Social Democratic Party during the 1980s

Lord Owen believes acquired hubris is not limited to politicians. "It exists in bankers," he says.

"If you look at the roots of the 2008-9 crisis you see in many major banks that their chief executives were making decisions based on a lot of the characteristics of somebody suffering from hubris syndrome."

Some research gives backing to these conclusions.

"Excessive winning increases testosterone. That increases [brain chemical] dopamine activity and the reward network," says Ian Robertson, Professor of Psychology at Trinity College Dublin.

"When you increase dopamine activity too much or for too long a time, you actually disrupt the judgement of the brain."

Walk away?

Journalist Wilf Mbanga believes some the symptoms of hubris syndrome apply to Robert Mugabe.

Mbanga once knew Mugabe so well they would listen to Jim Reeves tracks together.

"I was a fanatical supporter of Mugabe and his party," he says.

But today, he says, Mugabe has changed. "Now he believes he owns Zimbabwe. It is personal property now."

A few politicians walk away from power.

Nelson Mandela, for example, stood down after just one term and the current British Prime Minister, David Cameron, has said he won't seek to carry on after the next election.

But hubris, or sheer ambition, drives many to stay on for as long as they can. And the advantages of incumbency mean many will manage to do so - even into their dotage.

Constitutional term limits don't always work but for those who want to restrain power hungry leaders, they are perhaps the most effective tool available.

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

- Published7 July 2015

- Published14 October 2015