Is public service broadcasting in terminal decline?

- Published

Public service broadcasters all over the world are coming under increasing pressure to justify their funding models. So is it inevitable that these broadcasters will lose at least some of their public money, forcing them to adopt more commercial funding structures?

Would that actually be good for anyone? And what kind of impact would these big beasts have on a commercial sector that some say is already saturated?

The BBC led the way in public service broadcasting in the 1920s with the mandate to "inform, educate and entertain", a model that many have followed. Publicly funded, with government backing, but crucially - independent from government influence - as opposed to the state broadcasters of China and North Korea, for example.

But is the model sustainable?

In Canada, a Senate committee has just published a report on public broadcaster CBC that they've entitled Time for Change, external. The 22 reforms it recommends, critics argue, are a thinly disguised attempt to contract the range of services it offers.

In Australia, the government of Tony Abbott is "at war" with the ABC, if you believe the headlines. Recently, not only have ministers called for further cuts to the public service broadcaster, but the prime minister himself has directly criticised editorial decisions - demanding that "heads should roll".

Tony Abbott told ministers to boycott a popular talk show on the ABC

Subsidy?

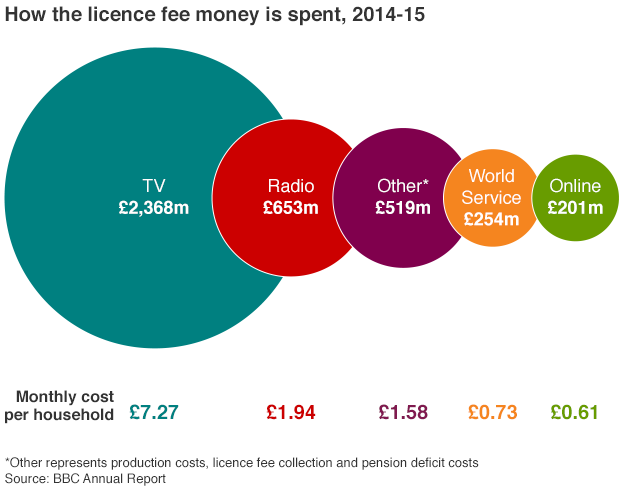

In Britain, the debate is over the future of the BBC licence fee - the flat rate payment made by every household owning a television, regardless of income.

With the BBC's Charter, the document governing how the BBC is run, up for review, the government has launched a public consultation period about the future of the broadcaster. John Whittingdale, the Culture Minister overseeing the process, has already described the BBC as "bloated".

The BBC does reach a massive global audience on TV, radio and online. More than 308 million people access its services in some way every week, largely paid for by the British licence fee payer, at about 40p (or 65 US cents) a day per household.

But many in the commercial sector complain that the sheer size of the BBC unfairly crowds out commercial rivals.

Allister Heath, deputy editor of the Daily Telegraph in London, told Newshour Extra that the BBC website in particular has become one of his paper's biggest rivals. "It's very, very good," he says, "but it's financed out of the licence fee and we see that as a subsidy."

David Elstein is chairman of OpenDemocracy.net, and former head of programming at BSkyB. He agrees, suggesting that the licence fee should be converted into a voluntary subscription model, rather like Netflix or Amazon Prime.

Like Allister Heath, he's also concerned about the reach of the BBC website - it's both "free and good", he says, but complains that its budget is "a phenomenal amount of money - and there is no commercial competitor in the world that can invest that kind of money".

Public support

But much of the content available on the BBC website is reworked material already available on radio and TV. Modern media exists on multiple platforms at the same time, and defenders of the BBC licence fee argue that it's essential that public service broadcasters occupy a space in all these areas.

There is much popular support for CBC in Canada

Dr Damian Tambini, director of the Media Policy Unit at the London School of Economics, points out that some governments, such as Japan's, had deliberately constrained the reach of public service broadcasters like the NHK, to prevent it from crushing the competition.

But many argue that the very concept of public service media is the responsibility to serve the whole population - reaching the audience in their preferred format, regardless of whether they are teenagers, commuters, or elderly people.

Former World Service presenter Robin Lustig told Newshour Extra: "The great joy of having public service broadcasting is that it's a form of entertainment, information and education which is not determined by advertisers or government interests. It's determined, imperfectly, by what viewers and listeners want."

And the statistics do seem to show that public service broadcasting is what the public wants.

In Canada, for example, a 2013 poll by the Friends of Canadian Public Broadcasting, external found that 80% of people nationwide wanted the CBC's level of funding to stay the same or even to be increased. Only 16% of Canadians supported cutting its budget.

As the debate continues on at least three different continents, Robin Lustig asks: "Who are the people who want to dilute the influence of public broadcasting?

"They are either commercial rivals who fear they are not making as much money as they would be able to, were it not for the public service broadcasters - or they are governments who want to have more control over what's being said."

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

- Published22 July 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015