Drone wars: Today’s weapon of choice?

- Published

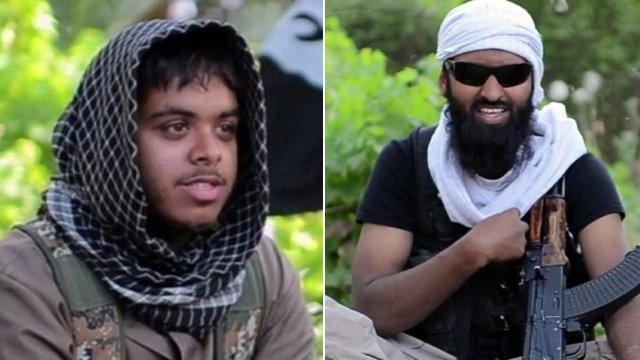

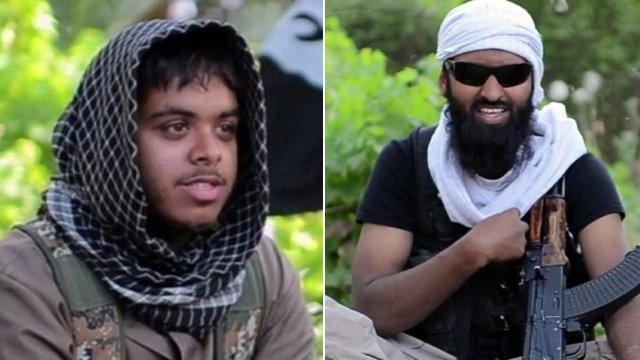

Reyaad Khan (left) and Ruhul Amin were killed by an RAF drone strike

Drone strikes are often controversial. They seem to allow the attacking nation to remain literally and metaphorically above the fray. Their own service personnel are not at risk.

And drones also seem to blur the boundaries between warfare on the one hand and counter-terrorism and law enforcement on the other.

No wonder then that the announcement by the British government that it was an RAF drone strike that had killed an alleged British member of the so-called Islamic State group in Syria was controversial.

British warplanes and drones are not generally operating against targets in Syria. Britain is not at war there. The man killed was a British citizen.

Human rights activists and opponents of capital punishment were quick to warn that the Cameron government was starting down a similar path to that pursued extensively by the United States, for whom the drone has become the counter-terrorist weapon of choice.

The British government insisted that the individual in question was plotting terror attacks in Britain and that there was no other feasible way of thwarting these plans.

This illustrates the extraordinary utility of armed drones - or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as they are also known - but also of the unanswered legal and moral implications of their broadening use.

Sophisticated strikes

Until now only a few countries have had the technology and the reconnaissance capabilities to allow them to use drones in this way. The US and Israel are probably the leading technological players with a number of their allies operating their systems.

A General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper stands on the runway in California

But the use of armed drones is spreading. Earlier this month Pakistan used an armed UAV, external - identified as a locally made Burraq - to attack a target in the tribal area of North Waziristan.

The apparent sophistication of this strike surprised many Western experts, hinting perhaps at the source of the technology involved, most probably China, external.

While the list of countries that have actually used armed drones in anger is small, it is slowly growing.

China and Iran too are believed to have operational armed drones and many other countries have expressed an interest in acquiring them. Even non-state actors such as Hezbollah have sought to use them, in its 2006 war with Israel., external

A study in June by the US think tank the Center for a New American Security noted that some 90 countries were now operating drones, external of one kind or another and at least 30 of them were either operating or seeking to develop or acquire armed versions.

All in the family...

Many of the world's most capable drones bear a striking resemblance, with technology either shared to some extent or directly copied.

Clockwise from top left: MQ-9 Reaper, MQ-1 Predator, Hermes 900, Wing Loong

The US Air Force's MQ-9 Reaper, a medium- to high-altitude endurance drone capable of flying at higher speeds and altitudes than its predecessor, the MQ-1 Predator. Reaper is also used by the RAF.

Israel's Hermes 900. Manufacturer: Elbit. Medium-altitude long endurance. First used in Operation Protective Edge over Gaza.

China's Wing Loong. Manufacturer: Chengdu Aircraft Design & Research Institute. Programme started in 2005 but many see it as being based on the MQ-1 Predator.

While some people see armed drones as in some sense offering an "unfair" advantage because none of the drone-operating nation's personnel are put at risk, this is not the chief concern of strategists.

It would be naive in the extreme to imagine that war - distasteful as it is - should in some sense be "fair". Minimising the risk to one's own forces and maximising the threat to the enemy is after all a large part of what warfare is all about.

Nonetheless armed drones are seen as significantly destabilising weapons.

It emerged in 2013 that RAF pilots operating on British soil had flown drone missions over Afghanistan

Their ability to respond rapidly, to loiter over an area for hours and to pick out a small target and strike it with a high degree of precision, all mean that they are weapons that are likely to be resorted to with increasing frequency.

The fact that they involve less risk to the personnel of the nation using them and the fact that their strikes are discrete and small-scale, again make them an attractive option.

A June 2014 report from the Council on Foreign Relations, external suggested that drones should thus be treated as a distinct class of weapon.

Constraints on drone proliferation, it argued, should be strengthened, and the US, as the major user, should establish norms for their use. (Critics of the US would argue that the way Washington has used drones in the post-9/11 world has already established a highly destabilising norm).

War or counter-terrorism?

Clearly drones are not just weapons of war.

The US has conducted hundreds of drone strikes, often in countries where it is not technically at war.

The effectiveness of this drone campaign has often been called into question. Has it really diminished the size of the targeted groups - and how many innocent civilians have been killed in the process?

Drones straddle the line between war and counter-terrorism, which in many Western countries is largely a civil responsibility. No wonder then that their critics sometimes describe their use as "extra-judicial killing".

Of course governments counter by insisting, as the British government did for its recent Syria strike, that their use is wholly legal under international law.

The security dilemmas are compounded by the spread of civil drone technology. This too is moving ahead rapidly - you can buy relatively sophisticated, although of course unarmed, "flyers" in many High Streets - and this technology is likely to be "weaponised" by criminal or terrorist groups.

The strategic, legal and moral problems posed by the use of armed drones are immense and will only increase as the weapons spread to more and more countries.

Some would like clear international understandings regarding the transfer of armed drones and their technologies, as well as some kind of international understanding - treaty or otherwise - that would circumscribe the use of this unique class of weapon.

- Published8 September 2015

- Published8 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published12 October 2017