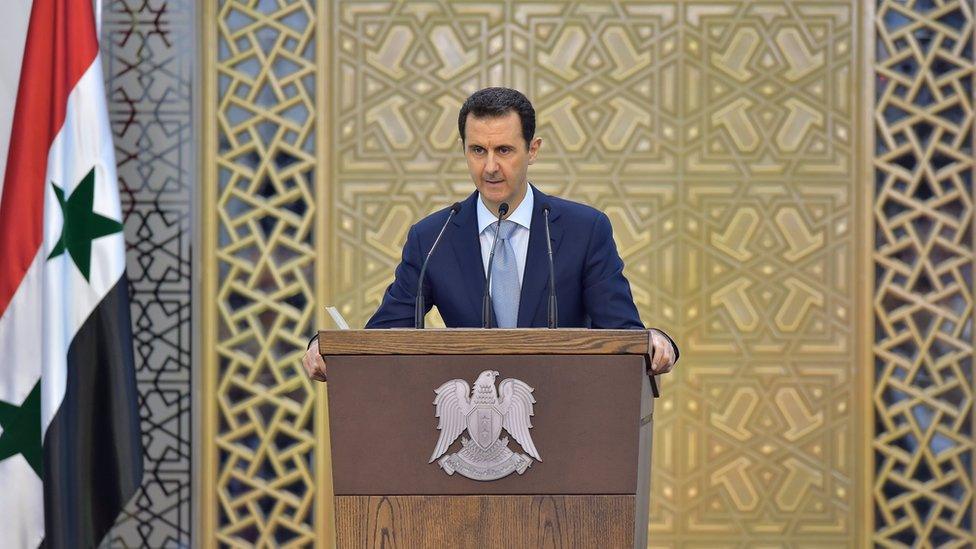

Syria conflict: If not Assad, then who?

- Published

One diplomat said Bashar al-Assad leaving power before a transitional process no longer makes sense

The most concerted diplomatic push so far to end Syria's punishing war has concentrated minds on all sides of a bitter divide.

Conversations with Arab and Western sources make it clear there is a major unifying goal in these new discussions: to avoid the collapse of Syria's security forces and its civilian institutions.

That means all sides are now moving away from rigid positions taken when Syria's uprising erupted more than four years ago.

"[President Bashar al-] Assad leaving before the process starts doesn't make sense any more," a senior Arab diplomat in the region told me. "If he leaves suddenly, two-thirds of his commanders would go with him and Syria would collapse."

The exodus from Syria has focussed minds

The steady rise of the so-called Islamic State, and mounting pressures on a stretched Syrian army has rung alarm bells over the threat of an ungoverned Syria falling into the hands of extremists.

The risk posed by another fractured Middle East country is now too big to ignore. So is this summer's tragic exodus of hundreds of thousands of Syrians desperate to reach Europe. Then, the startling September surprise of Russia's air sorties into Syria set the stage for the most determined diplomacy of Syria's crisis.

Ideas emerging from Arab and Western capitals include a ceasefire, an amnesty for forces on both sides, and a transitional government intended to ensure an orderly process that would lead to the drafting of a new constitution and elections. There's talk of a transition that could last up to two years.

Some of these ideas are also appearing in reports about proposals coming from Russia and Iran. Iran has had its own "four-point plan" for a few years, which was studied with interest by the UN. But it stayed on the shelf while Iran was kept out of talks.

Credible alternatives?

Integrating an array of armed forces will be fraught with difficulties, if not dangers, but there is a hope that the reform of civilian structures is within easier reach.

Sources speak of discussions concerning which senior members of President Assad's team would be asked to leave - a figure of 10 -15 people was cited.

There's also a hope that new, more credible, leaders will emerge from the opposition during this period to replace figures seen as lacking support inside Syria.

"They're nice people but they have no base," is how one source backing the opposition put it.

Russia has recently stepped up military support for President Assad

Having convincing alternatives to take charge is seen as crucial to reassure Russia and Iran, who back President Assad. I'm told that names of possible candidates are already being drawn up and shared.

An official involved in recent talks with Russia quoted the Russians in this way: "Where is the opposition? If you can assure us it will work we are not wedded to Assad."

Iran and Russia recently stepped up their military support to bolster President Assad's embattled position on many key fronts. But in private, officials have said for some time that their objective is to "save Syria, not Assad."

The biggest gap, however, is still over how long President Assad can remain part of the process. His opponents insist this process cannot start with him unless it is absolutely clear it will end without him.

Tough choices

This week's press conference in Riyadh, which saw Saudi Arabia's Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir and the visiting British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond calling for a fixed departure provoked a sharp rebuke from Damascus.

Syrian Information Minister Umran al-Zu'bi condemned those with "blood on their hands" who were "speaking about the internal affairs of a country that has always been and will remain free and owns its decisions."

John Kerry has visited Saudi officials for talks

In the end, it is Syrians themselves who will have to make the tough choices. Members of the Free Syrian Army, seen as moderate forces, have been visiting Moscow in a sign that there may be room for discussion. But powerful groups linked to al-Qaeda, as well as Islamic State fighters, want nothing to do with this negotiated process. They're on terrorist black lists so they aren't invited anyway, but there is still a long hard campaign ahead to try to dislodge them.

And there is still deep scepticism that gaps in the negotiating process can be closed, and still deep-seated suspicion and animosity between arch rivals Iran and Saud Arabia, along with some other Gulf states.

Saudi King Salman received telephone calls from President Vladimir Putin and President Barack Obama in the past week, and visits from US Secretary of State John Kerry and Philip Hammond. The Saudi monarch is understood to have given his blessing to Iran's inclusion in the process. Foreign Minister Al-Jubeir told me: "I wouldn't call it a place at the negotiating table, it's about being part of the conversation."

And if this fails, there is clearly a Plan B on all sides, for an accelerated military option. Military supplies are already being stepped up even as talks proceed.

"It's not going to be easy and the longer it takes, the more complicated it gets," is how a senior Arab diplomat in the region put it. "That's why an orderly process is better than a military one where institutions collapse."