Extreme poverty: Can it become a thing of the past?

- Published

The countdown has already begun towards the number one goal of the ambitious international development agenda set by global leaders last September.

Amid the fanfare of the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals at the UN, the leaders pledged that by 2030 nobody anywhere in the world would live in extreme poverty - currently measured as living on less than $1.25 (88p) a day.

The key aim of the Millennium Development Goals - replaced by the SDGs at the turn of the year - was that extreme poverty would be halved.

That happened during the lifetime of the MDGs and it was no mean achievement. But it was largely because of progress in the world's two most populous nations - China and India.

Development experts say the challenge now of finishing the job in just 15 years will be even more demanding.

What are the chances of ending extreme poverty by 2030?

Millions who have been left behind so far in the battle against poverty will not be lifted out of it by economic growth alone - instability, proneness to disasters, weak governance, corruption and discrimination of various kinds are among the factors that can make it so hard to escape severe poverty.

Change - but to what effect?

After decades of covering the complexities of development and humanitarian crises as a BBC correspondent, I have just made a return journey to countries and to hard-pressed families I have reported on in the past.

When I met Makaru Rana in the late 90s in the state of Odisha in eastern India, he and his family were just setting off to work for several months in the brick kilns of Andhra Pradesh.

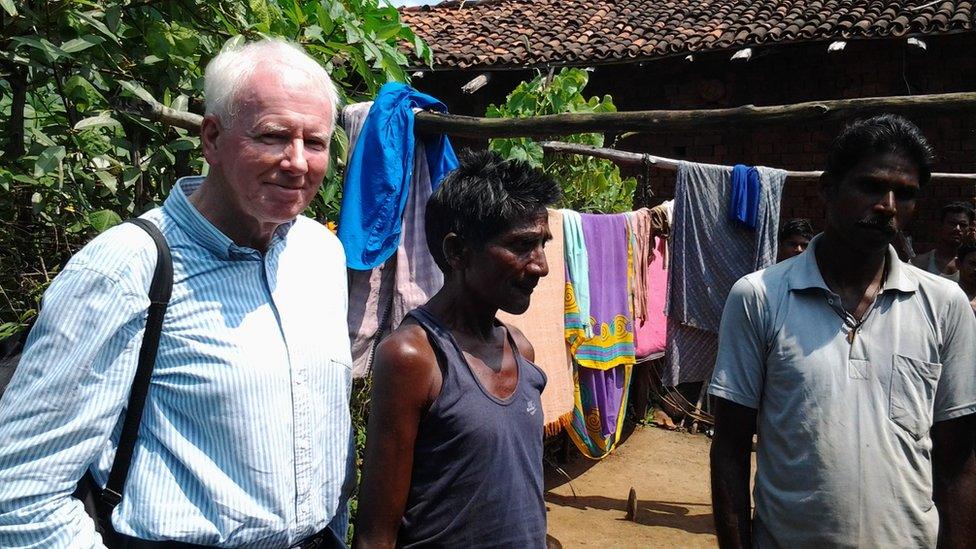

Mike Wooldridge returned to Odisha to visit Makaru and his family after 18 years

Their small farming community had been hit by drought and a bad harvest and many families were undertaking the same long train journey in the hope of earning enough to see them through the lean times. But I followed Makaru to the brick kilns and saw what a tough life they had there and how little they would eventually take away with them.

Much has changed in India in the intervening years. But meeting Makaru and his family again now, it quickly became obvious how little the pattern of their lives has been affected. And drought has hit them once again.

Today there are more schemes to help the poor - including rice rations, 100 days of guaranteed labour and pensions for the elderly. But the actual provision of such social protection is erratic, according to villagers.

Makaru (third from left) and his family still migrate over 1,000km every year to work in the brick kilns of Andhra Pradesh

Makaru has a black-and-white TV now, run off a car battery. But his 18-year-old daughter Niladri had to finish school two years ago because of lack of funds.

And now they were about to go to the brick kilns again - though today the villagers have been able to bargain for higher wages there.

Even so, while we were with Makaru and his family we worked through their household finances and calculated that their total income last year - from both the brick kilns and the sale of the rice they produce beyond their own needs - was $1,550 (£1,080)

for four people (Makaru, his wife and two youngest children), well below the threshold of extreme poverty.

Loss and goals

Back in 2002, I went to Malawi to follow up a letter I received from a post office clerk, Innocent Nkhoma, who had heard me on the BBC. He wrote about famine striking his area and of the loss of his daughter.

Landlocked Malawi remains a deeply impoverished country, despite having received substantial aid and never experiencing the impact of conflict.

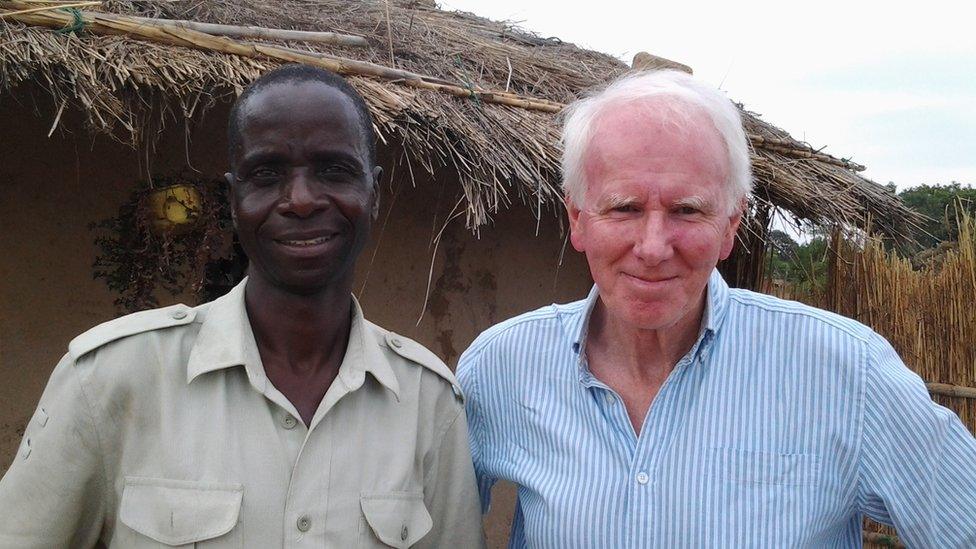

Mike Wooldridge first met Innocent in 2002

Innocent and Mike today

Returning to meet Innocent 13 years on, I found that he believes his family are actually worse off today.

The major change in their circumstances is that the post office was privatised in 2003 and he lost his job. It was several years before he finally found a more poorly paid permanent job as an assistant in a small rural health centre.

Innocent and his wife Agnes lost a house that had been provided by the government and they also have to rent a piece of land to fend for the family, now doubled in size to six children.

Innocent told us he earns $50-$60 a month from his job today at the clinic - to take care of the whole family.

In his late 40s, Innocent wants to study further to improve his chances of earning more. And he would like Agnes to run a small business.

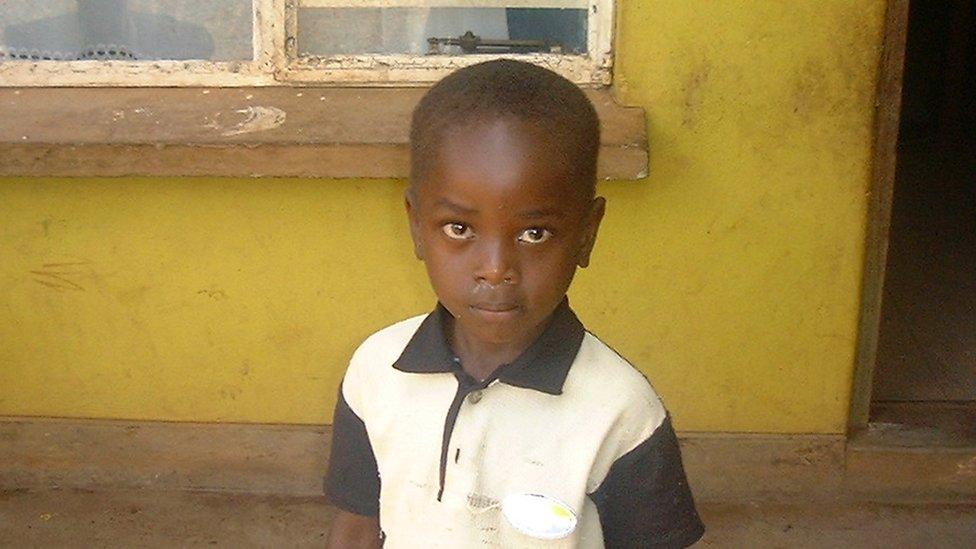

Innocent and his family are worse off today than they were in 2002

The daily lives of such families are the reality check that reaches beyond the rhetoric of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The SDGs call for the income of the poorest 40% in each country to grow at a higher rate than the overall average. But squaring growth with the urgent need to do more to protect the planet is likely to be one of the core challenges.

History tells us that there is no single blueprint for ending poverty, particularly at a time like this when there is such mass displacement of people caused by conflict as well as by impoverishment.

It is also clear today that some of the best solutions to poverty come from the ground up.

But if the ambitions of the SDGs are to be achieved and sceptics confounded, it may also depend on whether the political will behind them is itself sustained.

What are the UN's Sustainable Development Goals?

Officially known as Transforming Our World - the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, external, they include:

End poverty in all its forms everywhere

End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Mike Wooldridge is a former East Africa, Southern Africa, South Asia and World Affairs Correspondent for BBC News. He is the presenter of the BBC World Service documentary, The New Face of Development (a Ruth Evans production).

- Published25 September 2015

- Published24 September 2015