Trump travel ban: US residents trapped in legal limbo at airport

- Published

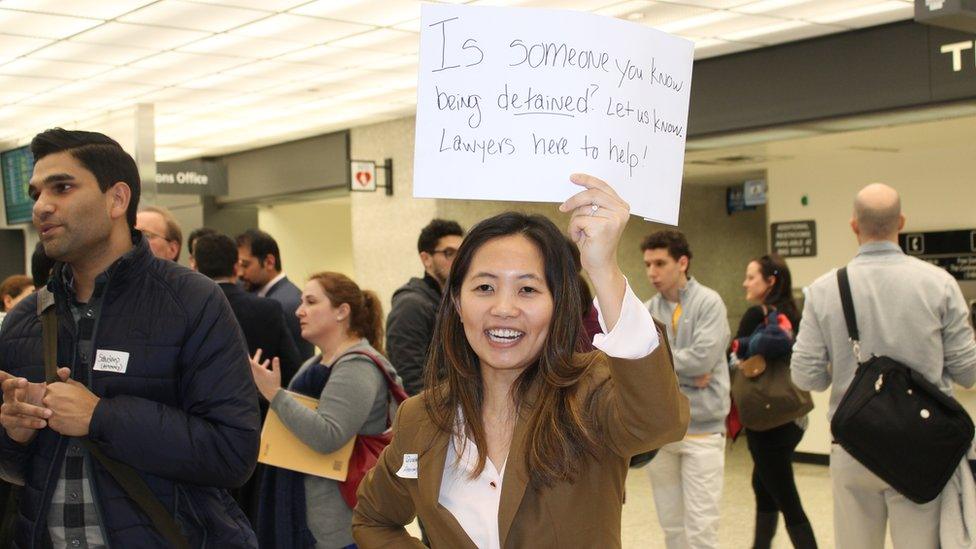

Protesters gather at Dulles airport: "Welcome to the USA!"

Said Hajouli, a second-year medical resident, had waited over a year to see his bride.

They met in Turkey, after "Leen" - Said did not want to use her real name - fled her university in Syria when the war broke out.

They were engaged for a year, married in 2015, then spent only one week together as husband and wife before Said had to return to Virginia on his J-1 visa, a non-immigrant visa commonly given to scholars and doctors.

In the meantime, the couple applied and were approved for a J-2 visa for Leen, which is a permit reserved for spouses and dependents of J-1 holders.

Finally, on Saturday 28 January, Leen boarded a flight in Istanbul bound for Dulles International Airport in Virginia, about 45 minutes outside of Washington DC. It was supposed to be a happy day.

"It was supposed to be, but I don't know what's going to happen," 29-year-old Said said, not long after arriving at Dulles.

Almost exactly 24 hours earlier, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled, "Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States". It shut down the US refugee programme for 120 days, indefinitely suspended the resettlement of Syrian refugees, and halted all immigration to the US from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Somalia, Libya, Sudan and Yemen for 90 days.

The order led to chaos at airports all over the world. Travellers were prevented from boarding planes abroad and, in some cases, were pulled off flights. They were detained at US airports. And there seemed to have been little instructions given to US Customs and Border Patrol on how to handle refugee and immigrant arrivals under the new rules.

Lawyers gathered to represent those facing travel bans

Earlier that morning, Said's friend's wife also attempted to enter the country with a J-2 visa, but he says she was immediately stopped and sent back.

So, instead of flowers, Said brought Rob Robertson to the airport, a tall, burly immigration lawyer. Said had found him just hours earlier after putting out a desperate plea for help on social media.

"They've done everything they need to do. It's already clear she's not a threat," said Mr Robertson.

"It worries me that they're just going to turn around and send them back, pursuant to an executive order that is not law, that does not override the Immigration and Nationality Act," he said, referring to the 1965 law that bans discrimination against immigrants based on "nationality, place of birth, or place of residence".

Protesters against the ban also gathered at New York's JFK Airport

Mr Robertson was one of roughly 30 volunteer lawyers who showed up to Dulles on Saturday afternoon. They deployed en masse following news that two Iraqi men with valid visas were detained at John F Kennedy Airport, in New York, and faced deportation.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued on their behalf and they were later released. Rumours spread that more were trapped in legal limbo at other airports around the country - including Dulles.

"This is not the country I was born in. This is not the country that I loved," said lawyer Lena Albibi, who was moved to tears. "It's very painful seeing this happen… They're breaking families apart."

Reaching prospective clients was a tricky errand for the lawyers, since anyone who needed legal help - travellers being detained in the "secondary inspection" area of US Customs and Border Patrol at Dulles - had no way to communicate with lawyers waiting outside.

Lawyer Lena Albibi said this did not feel like the US she knew

"We cannot get the information that we need so we can figure out how we can assist them," said immigration lawyer Sari Long. "We're trying to do our best to canvas family members."

Dispersed in the waiting area near baggage claim number 15 were people like Elmira Tayary, who had no idea she would need a lawyer to collect her 63-year-old mother, a green-card holder. Just hours earlier, Department of Homeland Security officials had revealed that the executive order would extend to permanent residents of the US coming from the seven banned countries.

Tayary said her mother splits her time between the US and Iran, and has for years.

"I'm very, very sad, but I'm hopeful she may show up any minute," said Elmira. "This is very disappointing."

Relatives and supporters waited to greet arrivals who had been detained

As hours ticked by, and more and more protesters arrived carrying signs that read "Refugees Are Welcome" and "Love Your Neighbour", it became clear that something like 50 to 60 people, including green-card holders, were being held at customs. Lawyers were still not permitted to speak to them.

However, there were small acts of rebellion. Employees of the airport itself managed to ferry information to family members who were waiting, including Elmira, to tell them that green card holders would soon be on their way.

Immediately soothed, Elmira bought her mother a red-white-and-blue balloon.

One by one, the permanent residents were released, walking down a corridor now teeming with demonstrators shouting "Welcome home!" and singing "This Land is My Land".

'We are not bad people'

Ali and his wife Hajer wore weary smiles as they pushed their luggage through the gauntlet of well-wishers, their 11- and 7-year-old boys in tow. Someone handed Hajer flowers.

Ali worked for three years as an interpreter for the US Army and gained admittance to the US through a Special Immigrant Visa, reserved for Iraqi and Afghan nationals who face threats of violence for working for Americans during the conflicts there.

He now has a green card, and returned to Iraq for his father's funeral, only to be delayed for hours for questioning at Dulles.

"We are not terrorists. We are not bad people," said Ali. "It's so hard. I hope they will change their minds on this position."

US citizen Alaa was finally able to connect with his wife Jinan, a green card holder, only after she answered a series of questions about her family and her husband's business.

"That's way over the limit. She's got a green card," Alaa said.

"Are we going to blow up our system because we are afraid? Then, you know, whoever we are afraid from are winning."

Just then, a thin man carrying a sign that read "This Veteran Stands With You" stopped Alaa, told him he is an Iraq veteran, and with little explanation fastened a Purple Heart medal to Alaa's jacket.

"That's a great thing, that's a great thing!" Alaa cried, elated. "This is what America is all about!"

Ali, Hajer and their sons, legal residents in the US, finally make it through to the arrivals hall

As the green-card holders began to depart, more good news arrived - first a judge in Brooklyn declared that deporting refugees and valid visa holders who'd already arrived in US airports would cause "irreparable harm", thereby blocking the deportations. Next, a judge in Virginia issued a temporary restraining order to stop the expulsion of green card holders.

Each time the news arrived, the lawyers huddled together and then broke out into rowdy cheers.

"We are optimistic that pretty soon all those people back there will be allowed to come through," said lawyer Dan Press.

By the time some detainees made it through, they were so exhausted that several fell weeping into the arms of loved ones - to the frenzied glee of the now-enormous protest group.

It wasn't all good news. Rumours that deportations took place continued to swirl, though it is unclear how many. The Virginia court decision lasts only a week and Trump's executive order still holds for anyone who did not make it to US shores in time for this brief, legal reprieve.

By 11 pm, Said still had no definitive answer about his wife, Leen. She called to say she was being sent back to Turkey, but then later was shuffled off to another room in customs.

"She may come walking out of there for all I know," said Said's lawyer.

So Said leaned against a wall, eyes fixed on the path out of customs, and waited, as patiently as the previous year.

- Published29 January 2017

- Published10 February 2017

- Published29 January 2017