Blue Whale: Should you be worried about online pressure groups?

- Published

Concerns are growing over suspected links between teenage suicides and online pressure groups

Reports are circulating in the media of vulnerable people being encouraged to take their own lives by following a series of online challenges.

In Russia, the deaths of some teenagers have been linked to the 'Blue Whale' challenge - though these reports have not been confirmed.

The idea is that individuals are invited to complete a number of tasks within a 50-day period. The tasks become increasingly harmful and end with the individual being challenged to take their own life.

There is concern that the idea is spreading around the world on social media networks.

With questions over whether or not the Blue Whale challenge actually exists, and with no confirmed link between the deaths in Russia and Blue Whale, how concerned should you be?

What is Blue Whale?

There is some confusion about the origin of Blue Whale, but the title is believed to be a reference to an act carried out by some blue whales, who appear to beach themselves on purpose, causing them to die.

The name is apparently being used by an alleged online pressure group, which is said to assign a curator to individual participants who then encourages them to complete tests over the course of 50 days.

These assigned tasks reportedly escalate from straightforward demands such as watching a macabre video or horror film to something more sinister - even leading to suicide.

Unfortunately it is not unusual for teenagers to be drawn to social media groups that ultimately have a detrimental effect on their mental health.

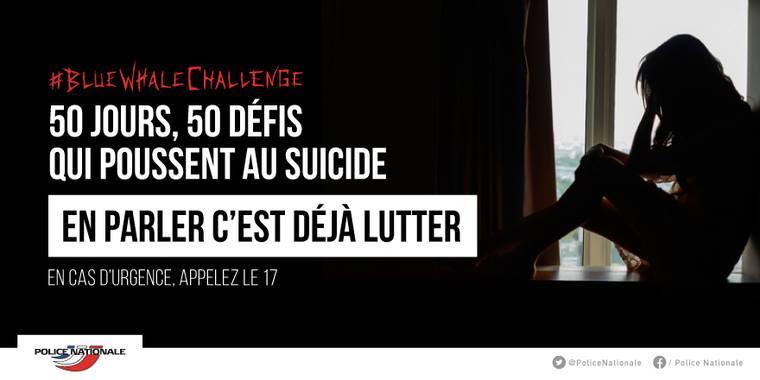

French police posted information about the phenomenon on Facebook

The online group associated with the Blue Whale reports is said to have thousands of members and subscribers on Facebook and YouTube.

The name has cropped up in countries including Russia, Ukraine, Spain, Portugal, France and the UK.

How worried should I be?

Although authorities in Russia are reportedly investigating links between the suicides of a number of teenagers and online pressure groups, there have been no confirmed reports of links to Blue Whale.

What police are looking for in these criminal investigations are previous conversations between the deceased and social media users that may have had an influence on any actions taken.

There are also reports of suicide cases being investigated in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Russia and Kyrgyzstan, with a focus on links to internet groups.

How can I spot the signs?

Children's advice groups such as the NSPCC, external can offer guidance on how to detect signs of online grooming - the building of an emotional connection to gain trust - and how to protect your child and prevent the situation from escalating.

There are a number of possible signs, but they are not always obvious because offenders exercise discretion in order to avoid being detected or identified.

Among the most common signs to watch out for include children who:

become very secretive, especially about what they are doing online

are spending a lot of time on the internet and social media

are switching screens on their device when approached

are withdrawn or angry after using the internet or sending text messages

have lots of new phone numbers or email addresses on their device

What should I do?

The Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (Ceop), a UK government agency, points out that sometimes change in a child's behaviour is completely normal and it is important not to overreact.

Having a calm and open conversation, Ceop says, is an effective way of determining the cause of any behavioural change, tackling any concerns head-on and offering support and reassurance.

An education programme set up by the organisation, ThinkUKnow, external, also says that it should be made clear to the individual when approached that any discussion is not going to result in punishment.

Children, it says, often avoid reporting their own concerns if they believe that their internet access will be revoked, for example.

Parents are advised to contact police if a child is thought to be in danger

Another UK-based advice group, Get Safe Online, external, told the BBC that it was aware of the "horrific" Blue Whale reports and said that it was unfortunate that groups were "willing to abuse these platforms".

The chief executive, Tony Neate, said dialogue was essential for addressing issues of peer pressure if a child is "acting strangely".

"It will allow them to take a step back, away from the pressures," he said, adding that this will help them to realise that it is "not something they have to, or should, be taking part in".

Mr Neate also advised against "blanket bans" on internet use and said that the importance of privacy settings should be explained to all users.

He said that speaking openly to other parents and teachers can help raise awareness of potential online threats and "open the path for other instances to be reported".

"Never shy away from reporting something that has occurred online to the police if you think your child, or someone else's child is in danger," Mr Neate said.

"This is how we can warn others and make sure teenagers don't get caught up in horrific games like this."

- Published26 April 2017

- Published6 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published29 September 2016