Female politicians and babies: a lose-lose situation?

- Published

Germany's Frauke Petry has five children

A new political party leader in New Zealand has reacted angrily to repeated questions about whether she plans to have children.

It is "unacceptable" to be getting those questions in 2017, the politician, Jacinda Ardern, said.

So what added scrutiny are female politicians under, and, conversely, can mothers sometimes use their family lives to their political advantage?

'Deliberately barren'

Some politicians have faced serious political attacks for not having children. New Zealanders just need to look across the water to Australia for one example: former Prime Minister Julia Gillard.

In an editorial, the Sydney Morning Herald wrote: "Her media persona does not fit the expectations of some voters: a single woman, childless, whose life is dedicated to her career."

This was one of the kinder comments. While leading Australia, Ms Gillard was called "deliberately barren, external" (by a senator from another party) and a "childless, atheist ex-communist" (by a rival from her own party).

She fought back against personal attacks against her, most notably with a searing tirade against the leader of the opposition, in which she said: "If he wants to know what misogyny looks like in modern Australia ... he needs a mirror."

Regarding voters' expectations, the newspaper may have had a point.

Political scientist Jessica Smith from Birkbeck College in London researches parenthood, gender and political leaders. She says that despite changing roles in society, the prominent idea of women is that they are mothers.

The "stereotype of women as primary caregivers" is still "very much a lens that we like to see women through", she told the BBC.

"There's also a trope that gets rolled out about career women, that if a woman doesn't have children she's sacrificed that for her career," she added.

Ms Smith says families have become more important in politics, as we "become more interested in the personalities or politicians", but she says "men seem to have an opt-out clause for discussions of family, which women don't".

The most powerful woman in Europe does not have children - and her country's media don't comment on it

It is a slightly different story in Germany.

Chancellor Angela Merkel may affectionately be called "mutti" (mum) by many Germans, but she has no biological children.

It is not common knowledge why she does not have children, and it is not a topic covered by the press; Germany has strong privacy laws and the media is much more policy-oriented than in other places.

But that has not stopped a political opponent trying to weaponise the issue during a tricky time.

Back in 2005, Ms Merkel was running against her predecessor, Gerhard Schröder, and it was his wife, Doris Schröder-Köpf, who commented she did "not embody with her biography the experiences of most women".

It was a clear reference to her not being a mother.

'A very real stake' in the future

This will sound like an echo to readers familiar with the Andrea Leadsom/Theresa May story from the UK last year. Both women were vying to become the leader of the same party - a leadership that would make them the prime minister.

Mother-of-three Mrs Leadsom told a daily newspaper that being a mum meant she had "a very real stake" in the country's future. It was interpreted as a dig against Mrs May, who has no children.

The comment backfired and, despite an apology, the episode brought down Mrs Leadsom's leadership bid.

But it still showed how a woman politician without children may find her childlessness is used against her.

The 'hockey mum'

Stereotypes often define women as more "communal and caring" than men, says Ms Smith, and motherhood can help them "extend on" that image.

Ms Smith says it is an image that politicians on the right of the political spectrum are best at exploiting, because it fits with traditional family values. She cites "hockey mom" Sarah Palin, who was governor of Alaska and campaigned for the US vice-presidency in 2008, as someone who did it well.

Sarah Palin appeared with her five children, her husband and her daughter's boyfriend at the Republican National Convention in 2008

Despite losing, Ms Palin made huge inroads; she was the first Republican woman to be on the vice-presidential ticket, and she became very well-known. She was a mum of five and called herself a "mama grizzly".

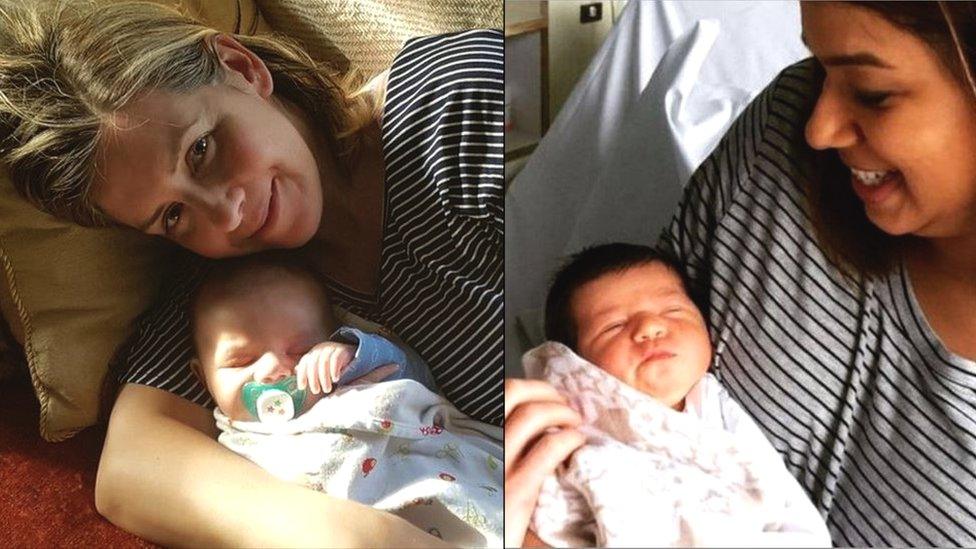

Frauke Petry in Germany is a more recent example of a right-wing mother whose children are central to her image.

The AfD leader was heavily pregnant with her fifth child at a party conference earlier this year. Last week she tweeted a picture of herself with her newborn, and the caption: "What's your reason to fight for Germany?"

And then there is US presidential runner-up Hillary Clinton, who has tried to soften her image by drawing on her status as a grandmother.

A double standard

For others, motherhood has been an obstacle.

In Japan in 2009 even the government minister tasked with raising the birth rate, Yuko Obuchi, said she was worried, external about juggling motherhood with her work.

Six years earlier, Russian property affairs minister Zumrud Rustamova noted while attending an important board meeting a week before her son was due that "people pretended that everything was all right, but would secretly be glancing at my huge belly".

In the UK, a 2012 study by Dr Rosie Campbell and Prof Sarah Childs found female MPs were more than twice as likely as people in the general population to have no children. They found the average age of female MPs' eldest child when they first entered parliament was 16, compared to 12 for men.

And while some things may lift those obstacles - a creche in government buildings, say, or jobshare arrangements for politicians, or allowing women to breastfeed in parliament - the extra scrutiny on women's family lives is often reflected by how voters see female candidates.

The Barbara Lee Family Foundation in the US wrote, external: "Voters recognise a double standard but actively and consciously participate in it.

"They express anxiety about a woman's job in office taking a backseat to her role at home and wonder who is taking care of the children, especially if they are young.

"If a candidate doesn't have children, voters worry that she may not be able to truly understand the concerns of families."

- Published2 August 2017

- Published27 June 2013

- Published11 May 2017

- Published1 June 2017

- Published3 June 2019