100 Women: Are rural women smashing the glass ceiling of agriculture?

- Published

"We have a lot of yams, we just need buyers," says Rosalina Ballesteros.

In Montes de Maria, the hilly region on the northern coast of Colombia where she lives and works, they had a particularly good harvest this year - but demand is low and yams are rotting.

So the community put out a call for help - via YouTube.

"We want to invite you to buy yams and help us," says the farmer in a 40-second video that went viral in Colombia.

"Yams are good for arthritis, for constipation and during the menopause," her fellow female farmers-turned-YouTubers add enthusiastically, marketing their produce.

'Everyone, let's eat yams': a YouTube video to help farmers in Colombia sell their produce

Farmer Ainagul Abdrakhmanova, a 32-year-old mother-of-five, also asked for support, but in her case from a women's self-help group that gathers in her remote mountainous village in central Kyrgystan.

"They helped me with the planting and to install drip irrigation," says Ms Abdrakhmanova, who now grows tomatoes, cucumbers and carrots; crops she was told would never prosper in her plot.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. In 2017, we're challenging them to tackle four of the biggest problems facing women today - the glass ceiling, female illiteracy, harassment in public spaces and sexism in sport.

With your help, they'll be coming up with real-life solutions and we want you to get involved with your ideas. Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

Meanwhile in northern Laos, Ms Vieng is now making a living from a mushroom farm in Luang Prabang.

Her community has a long tradition of collecting wild mushrooms for consumption but they knew little about how to cultivate them.

That was until Ms Vieng and others received training and resources to grow oyster mushrooms that they now sell in provincial markets.

Ms Vieng learnt mushroom cultivation techniques through the Agro-Biodiversity Project in 2014

In farms - and countries - miles apart, these women are part of a larger trend - the global increase in the relative number of female rural workers.

On average, women make up 43% of the agricultural labour force in developing countries and over the past two decades experts have observed the process of the "feminisation of agriculture".

There is "compelling evidence" that agriculture is feminising, says a 2016 report by the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), either because men move out of agricultural jobs or because women engage in different activities within this sector.

"Trends across the developing world show that women are playing a greater role and the proportion of them in agricultural employment is increasing significantly", says Libor Stloukal, policy officer in FAO's Department of Economic and Social Development.

Ainagul Abdrakhmanova (left) got support from other local women and a programme for economic empowerment of rural women in Kyrgyzstan

One quarter of all economically active women worldwide were engaged in agriculture in 2015, statistics from the International Labour Organisation show.

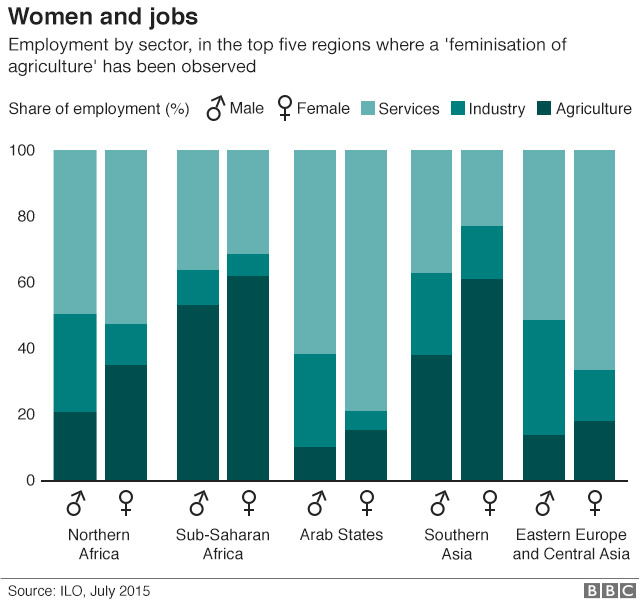

Yet global numbers mask considerable regional differences.

And while agriculture remains the most important source of employment by a wide margin in low-income countries, it has decreased remarkably in high-income nations as both men and women move to jobs in industries and services.

So where is the feminisation of agriculture really happening?

The trends are especially pronounced in North Africa, where the share of women in agriculture increased from about 30% to 43% between 1980 and 2010 (the latest comprehensive survey), as well as in the Near East, where it went from 35% to 48%.

The feminisation shift is also noticeable in East and South-East Asia, as well as Latin America.

While in most of sub-Saharan Africa the share of women in agriculture did not change significantly over three decades, it already exceeded 60% in countries such as Lesotho, Sierra Leone and Mozambique.

Experts see agriculture in this region as solidly feminised already.

The burden of male migration

Women's increasing presence in farms and plantations may be a positive development.

Some will become primary farmers or go from subsistence to wage employment, with their earnings contributing to households and communities.

Yet the so-called feminisation does not always translate into women's empowerment.

One of the key factors behind the trend is male outmigration.

"Young, rural men migrate to urban centres more than women," says Mr Stloukal.

"The feminisation is partly related to the increased availability of off-farm, more lucrative jobs for men in the industry and services sectors, as well as armed conflicts that have a larger impact on male populations."

Women who get left behind are often pushed to increase their working hours to compensate for the loss of male labour, experts say.

While women may now represent a larger share of the agricultural force, the types of rural jobs they can get have become more precarious.

Women are over-represented in unpaid, seasonal and part-time work.

Even when in paid employment, "they are more likely to be concentrated in labour-intensive, low-skilled jobs, and the few managerial positions are more likely to be taken by men," says a 2016 analysis by the World Bank.

"Even when women are farming, it is men who do the marketing and control the money," adds Dina Najjar, social and gender specialist at ICARDA, an international centre for agricultural research.

The 'sticky floor'

The available evidence suggests that women often earn less than men for equal work, affected by the so-called "sticky floor", which hinders pay parity for those at the bottom of the job scale as much as the "glass ceiling" does with those at the top end.

Household chores in rural areas often involve walking distances to collect water and fuel

Data documenting the gender earnings gap in rural settings is limited, yet a sample of 14 countries shows that on average women are paid 28% less.

There is also a "productivity gap", experts say, as women farmers' yield in developing countries is 20% to 30% lower on average - and the burden of household chores is to blame.

"In most societies, women are responsible for most of the household and child-rearing activities," says FAO. This additional set of responsibilities, which in rural areas may include tasks such as collecting water and fuel, "limits women's capacity to engage in income-earning activities".

"It is tough on women who have to 'use both hats' in challenging traditional contexts where change is not facilitated," says Marie-Louise Hayek, FAO's programme assistant.

From food processing to packing: developing skills in added-value tasks in the agricultural chain could narrow the gender pay gap, experts say

Helping hand

Yet the expansion of women's roles in agriculture is also bringing about some real benefits.

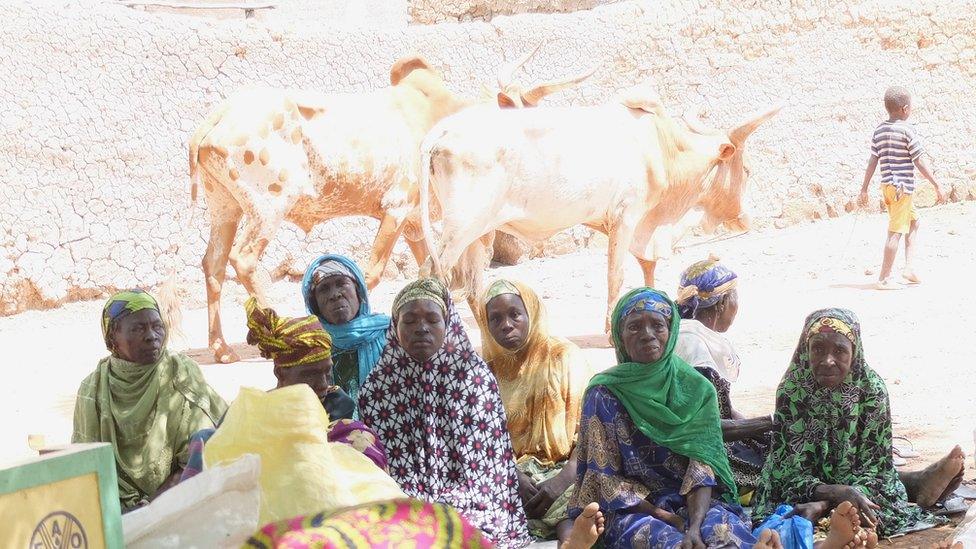

"Today I no longer worry about the end of the lean season… We are engaging in new activities which will make us stronger in trying times," says Sanihan Thera, a 28-year-old mother of four in the village of Baramadougou, in central Mali.

Ms Thera was a recipient of an "agricultural kit" provided by a FAO-run project in Mali and neighbouring Burkina Faso, which includes seeds - cowpea, millet and vegetables of high nutritional value - as a well as cash transfers and training to improve food security.

Sanihan lives in a household of 13 and she says living conditions are very difficult especially during the lean season

New techniques allowed these Malian women, responsible for feeding the family while men are away in seasonal jobs, to plant their whole plot for the first time in years.

"The harvest will certainly be enough to have food reserves for many months," says Ms Thera.

"This has allowed them to make their voices heard in the community, as some of these women report," says Fatouma Seid, the spokesperson for the project.

"It has also created a forum for women to give each other advice on everything from child nutrition to marital woes."

In Mali's patriarchal society women do not inherit permanent resources such as land

A range of organisations - from international bodies to NGOs and national governments - are working to introduce labour-saving technologies and to provide credit lines for women - two elements which many see as game-changers.

Critical to the social empowerment is the ownership of land - and in vast parts of the developing world women lack equal property rights with men.

"The issue of land ownership has to do with the scarcity of the resource. There is simply not enough land for everyone to own and men are competing for this resource, how are women going to get it?" says ICARDA's Dina Najjar.

A world map reveals that female agriculture holders - that is, the person who makes the main decisions regarding resources and management of an agricultural enterprise - are proportionally less than male holders in virtually every country where data is available.

"Evidence shows that land owning and managing is very empowering," says Ms Najjar.

"So changing policy is a start, but we need to work more aggressively on the social norms that prevent women from inheriting or acquiring land."

"Social norms change all the time, this can be changed," says Mr Stloukal.

Yet not all specialists are optimistic about the options that a feminised agriculture may open for women.

"In societies like our rural ones, where the generation that is involved in rural work is not young, it'll be most difficult to break societal norms in the near future," says Ms Hayek.

"[Feminisation of agriculture] could help close the gender gap, but it will take time."