100 Women: 'We can't teach girls of the future with books of the past'

- Published

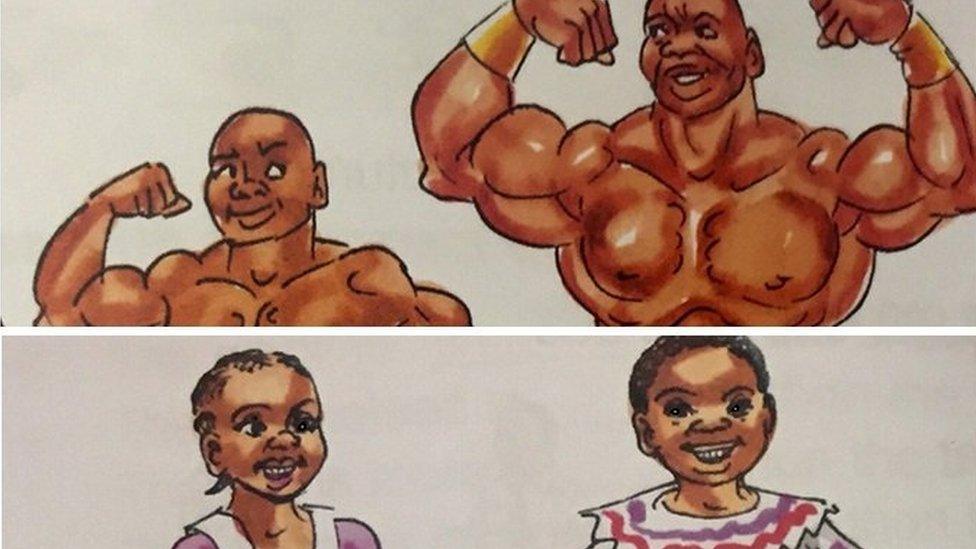

Strong boys, pretty girls in a Tanzanian textbook

In a textbook for students in Tanzania, boys are strong and athletic, while girls just look proud of their pretty frilly dresses.

In a primary school reader in Haiti, pupils learn that mothers "take care of the kids and prepare the food" as fathers work "in an office".

There's a Pakistani illustrated book where all politicians, authoritative and powerful, are male.

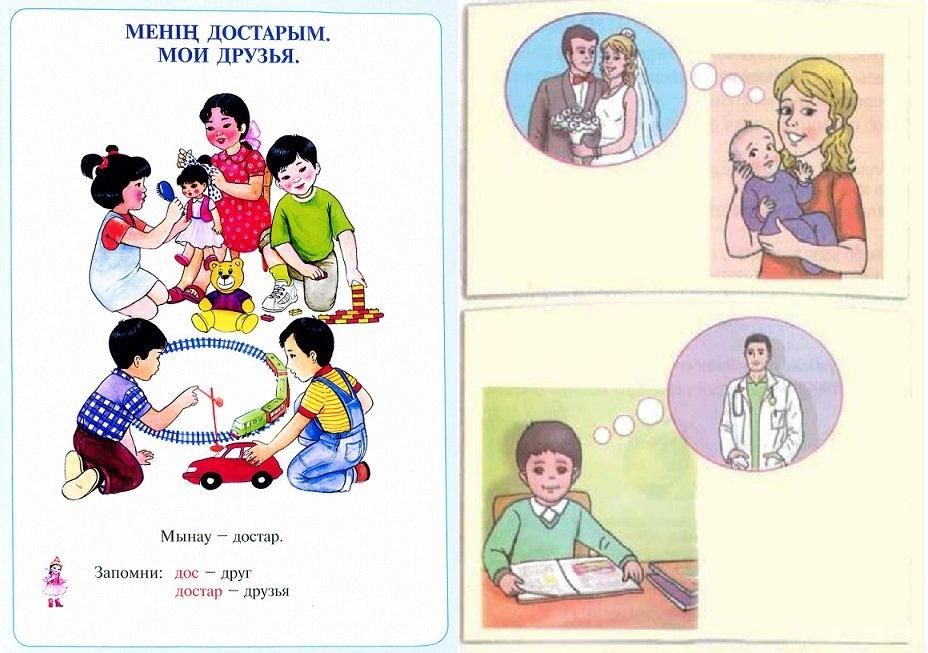

In Turkey, a cartoon of a boy shows him dreaming of becoming a doctor.

Meanwhile a girl imagines herself as a future bride in white gown.

The list goes on - and knows no geographical boundaries.

'A mother takes care of her children and cooks, a father works in the field or the office'

Gender bias is rife in primary school learning books and can be found, in a strikingly similar form, on every continent, various experts say.

It is a problem "hidden in plain sight".

"There are stereotypes of males and females camouflaged in what seems to be well-established roles for each gender," says sociologist Rae Lesser Blumberg.

Men make the money while women take care of the children: role stereotypes on display

Prof Blumberg, from the University of Virginia, has been studying textbooks from around the world for over a decade, and says she has seen women systematically written out, or portrayed in subservient roles.

"Gender bias is a low-profile education issue, not one that makes headlines when millions of children remain unschooled," she says.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. In 2017, we're challenging them to tackle four of the biggest problems facing women today - the glass ceiling, female illiteracy, harassment in public spaces and sexism in sport.

With your help, they'll be coming up with real-life solutions and we want you to get involved with your ideas. Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

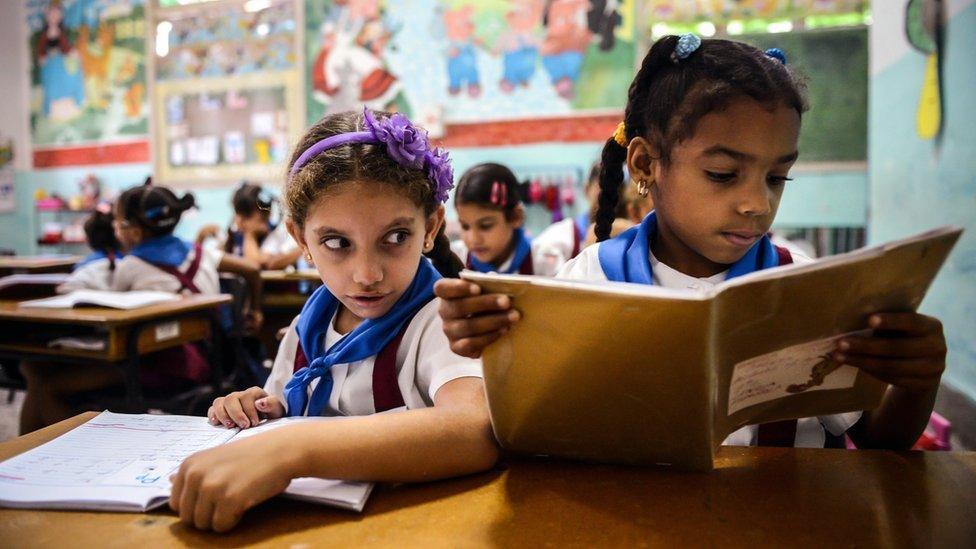

Although school enrolment has increased dramatically since 2000, Unesco estimates that over 60 million children still never set foot in a classroom - 54% of them are girls.

"These books perpetuate gender imbalance," says Prof Blumberg. "We cannot educate the children of the future with books from the past."

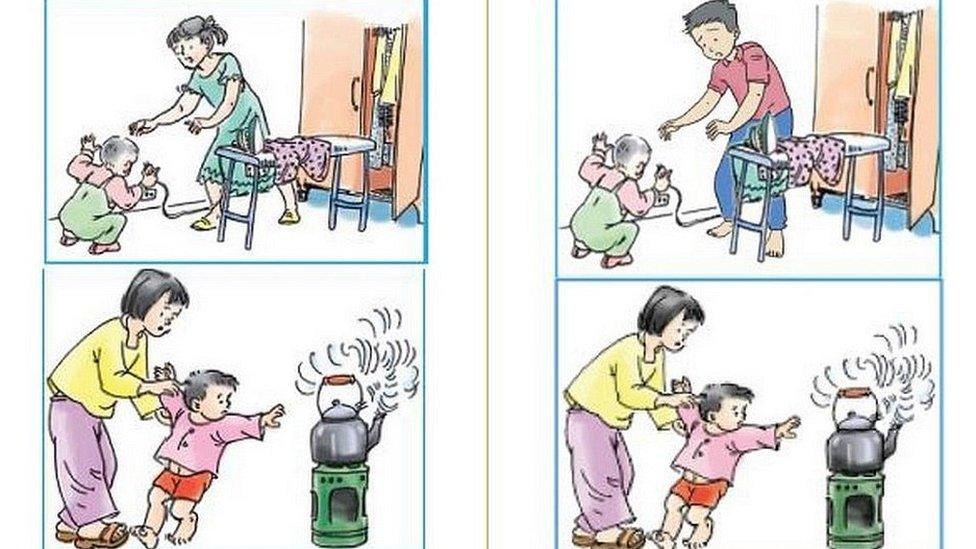

A Tunisian primary textbook portrays women cooking and cleaning

Invisible or stereotyped

Last year, the UN's education agency Unesco issued a stark warning, external.

Sexist attitudes are so pervasive that textbooks end up undermining the education of girls and limiting their career and life expectations, Unesco says - and they represent a "hidden obstacle" to achieving gender equality.

Whether measured in lines of text, proportion of named characters, mentions in titles, citations in indexes or other criteria, "surveys show that females are overwhelmingly underrepresented in textbooks and curricula", says University of Albany's Aaron Benavot, former director of Unesco's 2016 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) report.

A reader from DR Congo

The problem is threefold, experts say.

The most evident aspect is the use of gender-biased language, as often male words are chosen to mean all of humanity.

Then there's an issue of invisibility, as women are often absent from the texts, their roles in history and everyday life subsumed by male characters.

"There was one textbook about scientists I particularly remember, and the only woman in it was Marie Curie," says Prof Blumberg.

"But was she shown discovering radium? No, she was timidly peeking over her husband's shoulder as he spoke to somebody else, a man who looked elegant and distinguished."

Thirdly, there are traditional stereotypes in use about the jobs that men and women perform, both in the household and outside, as well as cliched social expectations and traits assigned to each gender.

All occupations are performed by men in this Italian schoolbook

An Italian textbook provides a striking example in a chapter that teaches vocabulary for different occupations, with 10 different options for men, from fireman to dentist, and none for women.

Meanwhile, women are often portrayed in domestic tasks, from cooking and washing to caring for the children and elderly.

"The concern is also that women are portrayed as passive, submissive, fulfilling these gender stereotypical roles," says education specialist Catherine Jere, a lecturer at the University of East Anglia who was also involved in the GEM report.

'If aliens came to visit...'

The problem is far from new. Textbooks have been under scrutiny since the 1980s, following a feminist push for reform mainly in developed countries.

A 2011 US study, often described as the largest-scale research ever conducted in this field looking at over 5,600 children's books published during the 20th century, estimated that males were represented almost twice as often in titles and 1.6 times more as central characters.

Since the problem was first identified, there has been progress in reducing sexism - but it has been "very slow", experts claim.

A 1962 textbook used in American schools - 'not a lot has changed,' education experts say

Some of the textbooks under scrutiny were published long ago, yet many remain in use - particularly in low-income countries and in schools that do not have a budget to replace them.

"It is getting worse by the year, because the world is progressing, women are entering new occupations and household roles are changing," says Prof Blumberg. "And books are not improving at the same pace, so the gap is widening."

"If aliens came to visit us, they would have no inkling as to what women actually do, occupationally and personally, by reading our school textbooks."

Universal concern

Research also shows that the problem is nearly universal. With differences in frequency and intensity, sexism is pervasive in schoolbooks from low- and high-income nations alike.

Data is scattered, but a sample of studies published over the last decade provides the evidence.

A history book for third graders in India, for instance, doesn't show any career women.

Gender-stereotyped games and aspirations in readers from Kazakhstan (left) and Turkey

An English language reader in use throughout Kenya portrays active men having "interesting ideas", while women and girls cook meals and plait dolls' hair.

Men made up 80% of characters in books designed by the ministry of education in Iran. India had only 6% of illustrations of women portrayed by themselves, and it was 7% in Georgia.

Maths textbooks in Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Togo and Tunisia had a proportion of female to male characters lower than 30%, as measured in a 2007 comparative study.

A survey of science books in the United Kingdom and China also revealed that a massive 87% of characters were male.

Girls partly see the world through their textbooks - so they will normalise stereotypes if that's what the readers show

In Australia, a study carried out in 2009 found that 57% of the characters in textbooks were men - despite there being more women than men in the country.

"One would think that textbooks in high-income countries would be a bit more forward-looking, yet in Australia twice as many men were portrayed in managerial roles and four times more in politics and government," says Prof Jere.

"There's an extreme case in a Chinese book, where there's only one heroine of the 1949 Communist Revolution", says Prof Blumberg.

"And she is not depicted fighting for legislation or on the frontline with Mao, she is shown giving an umbrella to a male guard standing under the rain."

Activities 'for mum and dad' in a Pakistani reader - while she cooks, he relaxes and reads

Occupations by gender in a Kenyan schoolbook

Influential teaching aid

Part of the problem, experts highlight, is that books construct a sense of what is normal in a society in the eyes of school children.

As they help establish a country's curricula, readers are a sanctioned educational tool - and a powerful one at that.

A pupil is estimated to read more than 32,000 pages of textbooks from elementary to high school levels, research shows. Around 75% of the class work and 90% of the homework is done from them, as well as a large proportion of teachers' planning.

Even though access to the internet and other digital resources expand the array of learning tools, "textbooks remain central especially in poor countries," says Aaron Benavot.

"When the textbooks show very narrow expectations about what boys and girls should be, then school children are socialised into that," says Prof Jere.

In many countries, the textbook is the linchpin of the education process

The impact that these books may have on children's views of the world has already been mapped by academic research.

An Israeli study on first graders, for instance, showed that those who were exposed to the portrayal of men and women as equals tended to think that most careers were appropriate for both girls and boys, while those learning from gender-biased textbooks were prone to find the stereotypes acceptable.

Also, a link has been suggested between the poor portrayal of female scientists on textbooks and the lower numbers of girls that go on to study STEM academic disciplines - science, technology, engineering and mathematics - in vast parts of the world.

Nigerian pupils learn about jobs and occupations in English with these portraits

Signs of progress

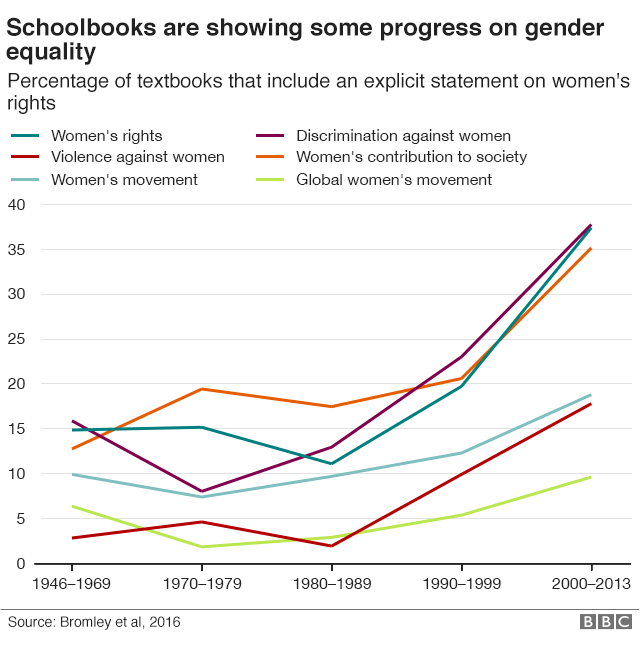

Yet some progress has been made over the past decade.

Unesco's GEM Report shows that content relating to gender equality has increased in textbooks across the world, with more frequent references to women's rights and gender discrimination, particularly in textbooks in Europe, North America and sub-Saharan Africa.

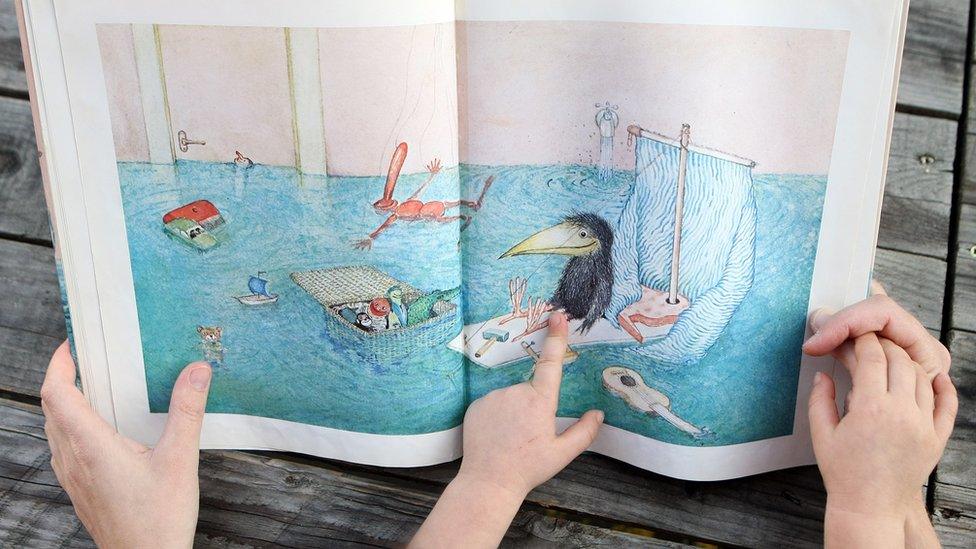

Some countries are spearheading change - and perhaps not surprisingly given its overall attitudes to gender, Sweden ranks at the top.

Some of the books in the national curricula incorporate gender-neutral characters and pronouns, as well as a more egalitarian portrayal of everyday lives.

"If you see somebody stirring a pot and wearing an apron in a Swedish book, there is a high chance it'll be a male," says Prof Blumberg.

Gender-neutral books improve learning results, some research shows

In Hong Kong research has documented an equal number of male and female characters in English language textbooks.

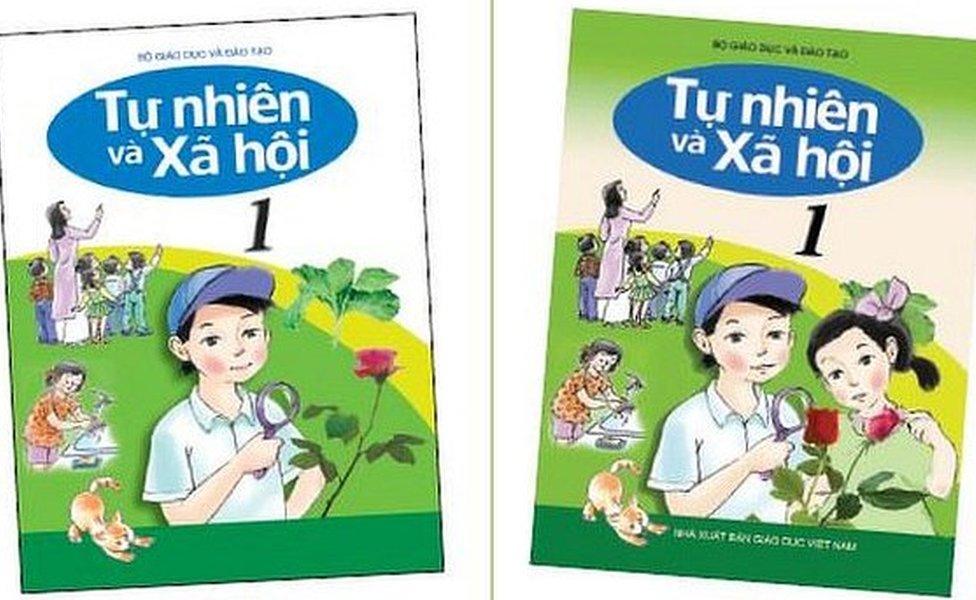

And progress has also been made in Jordan, the Palestinian territories, Vietnam, India, Pakistan, Costa Rica, Argentina and China.

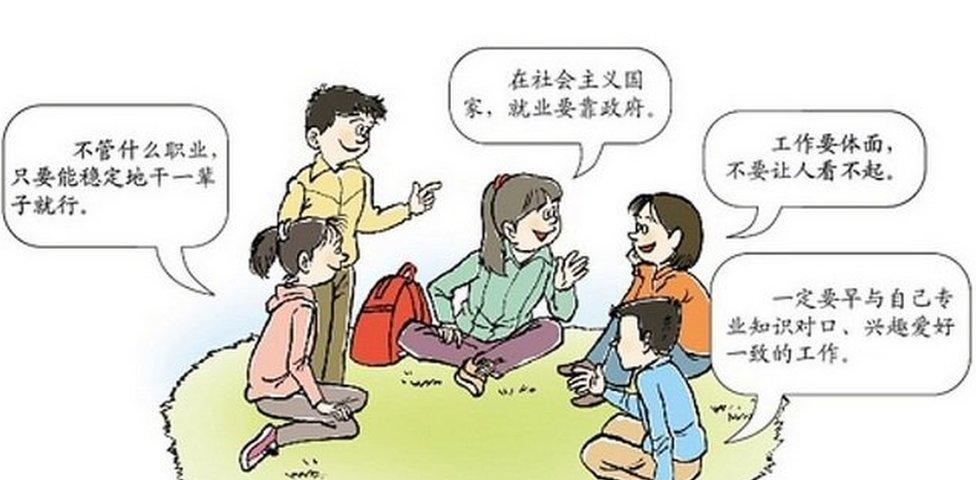

Improved version of a textbook in China, where young women and men discuss economics

But a comprehensive review of textbooks at national level is a lengthy and expensive process - which often becomes engulfed in budget cuts and red tape.

"Some of the changes have been superficial and the commitment of governments is not sustainable if there is a change of regime", says Mr. Benavot.

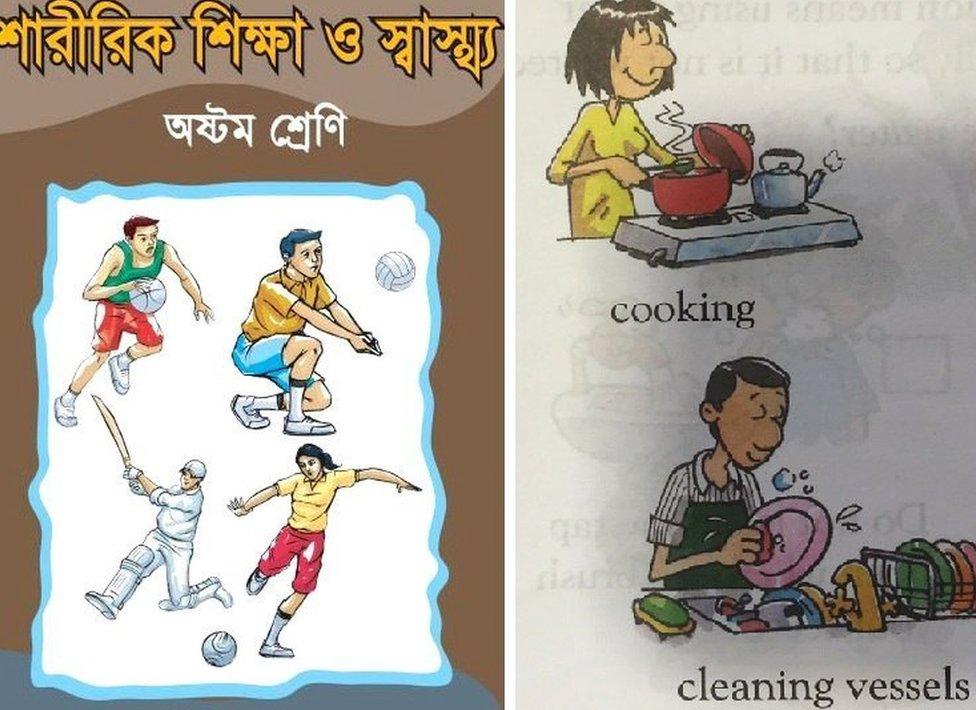

A textbook in Bangladesh portrays a woman playing football, while men wash the dishes in an Indian one

So experts suggest alternative methods to counterbalance ill texts in the classrooms.

Attempts in India and Malawi have been made, using the contested readers, to challenge students to identify gender bias and question stereotypes in group discussions.

"The problem can be compensated by calling attention to it and students tend to enjoy the 'detective work'," says Prof Blumberg.

"But we need to train teachers first and ultimately we need to rewrite these books if we want better education."

Before and after in Vietnamese textbook