Nobel peace prize: Ican award sends nuclear message

- Published

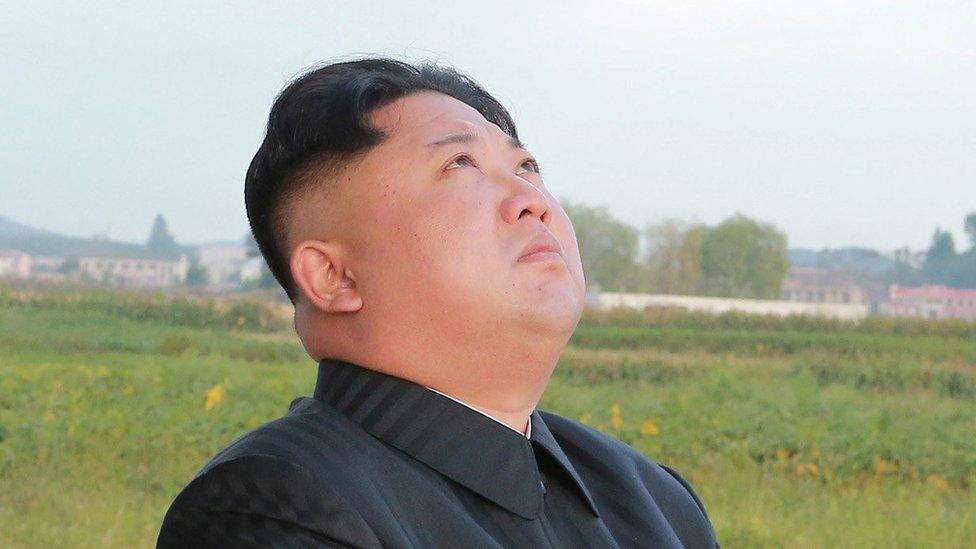

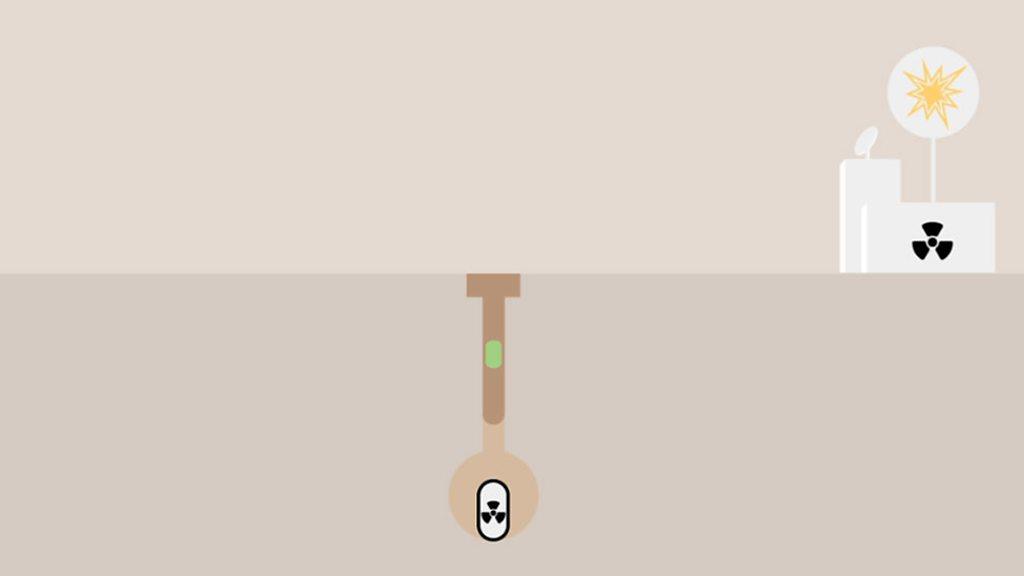

North Korea has been testing missiles that it hopes will carry a nuclear warhead

The Nobel Committee's decision to honour the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, known as Ican, provides a powerful and timely reinforcement of the opprobrium and concern that should be attached to nuclear weapons.

It comes at a moment when North Korea is actively developing its nuclear programme, the fate of the Iran nuclear deal is in the balance, and the US and Russia are both actively seeking to modernise their nuclear forces.

Ican campaigned for the drafting of an entirely new disarmament agreement - the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that was opened for signature at the UN in July this year.

This seeks to make nuclear weapons illegal under international law in the same way as the anti-personnel landmines treaty banned a whole category of weaponry.

But why is this new treaty needed at all? And why do its backers see it as being so important today?

There is of course already the long-standing Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) - a product of the Cold War years whose chief goal was to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons beyond the five established (or "declared") nuclear powers - Britain, France the US, China and the then Soviet Union.

Berit Reiss-Andersen, the Nobel committee chair, announces the winner.

The agreement was a series of bargains. Countries that joined the treaty as non-nuclear weapons states gave up the bomb in return for the benefits of peaceful nuclear technology.

Those five countries who were declared nuclear powers agreed to take steps progressively to give up their nuclear weapons.

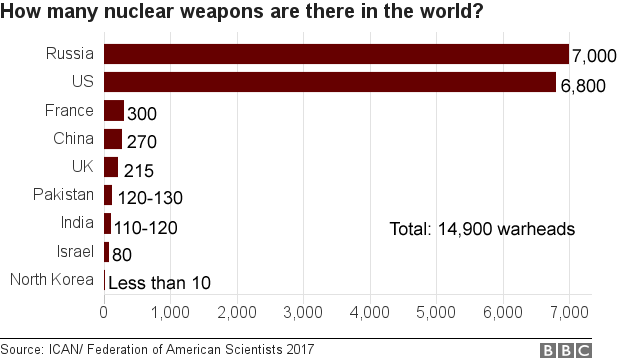

The Cold War saw a series of arms reduction agreements between the two superpowers. Britain and France also reduced their much smaller arsenals, though China, the latecomer to the nuclear game, has gradually built up its arsenal.

The problem is that full-scale nuclear disarmament has never really been on the agenda. The non-proliferation regime has, however, had much success. Only four additional countries today have nuclear weapons.

Three of them - India, Israel and Pakistan - never signed up to the agreement in the first place and North Korea abandoned the treaty regime to set about the development of a small nuclear arsenal.

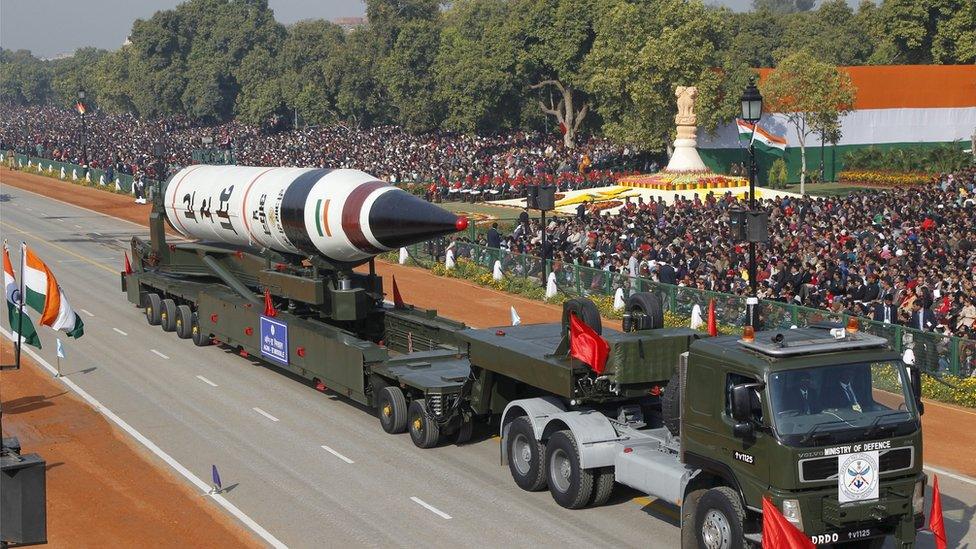

India's Agni-V missile can carry a nuclear warhead - the country did not sign the Non-Proliferation Treaty

But Ican believed that the NPT had not fulfilled its promise and that a parallel agreement was needed, modelled on the successful treaty to abolish anti-personnel landmines.

This would not begin with intergovernmental diplomacy but with grassroots activity. The goal was to get a new nuclear ban treaty opened for signature and then to campaign widely to change public opinion to compel governments to sign on.

Well that treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons is now a reality and 53 governments have signed up.

Of course the problem is that the nuclear weapons states are not among them. Nor are they likely to sign in the foreseeable future. The treaty though does set a legal norm and is a strong basis, campaigners believe, upon which to build.

Ican's Nobel Peace Prize certainly underscores the concern about nuclear weapons at a timely moment. North Korea is proceeding apace with its nuclear missile programmes, raising questions about what other countries in the region might do. Some voices in South Korea have already suggested that US tactical nuclear weapons should be deployed there.

North Korea has clearly decided that the best defence against regime change is nuclear. It has - rightly or wrongly - drawn lessons from the fate that befell Saddam Hussein in Iraq and the Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi.

North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un believes the best defence against regime change is nuclear weaponry

Elsewhere the nuclear deal that has constrained Iran's nuclear activities is under pressure from US President Donald Trump who, despite Iran being fully in compliance with the agreement, believes that it is not in America's national interest.

It is not clear yet if he is just seeking to register this opinion or whether he actually hopes that Congress will re-impose economic sanctions, effectively making the US, not Iran, non-compliant with the deal.

And beyond this, the whole fabric of arms control inherited from the Cold War is to some extent fraying.

There are strains between Moscow and Washington over the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty; the Open Skies Treaty; the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty and no indication that strategic arms reductions are going any further. Vital confidence-building and verification provisions will eventually lapse.

The US has imposed new sanctions on Iran over its recent missile tests

On the multilateral front, even great successes in arms control - the Chemical Weapons Convention for example, which had a high point when Syria was compelled to give up its chemical arsenal - now appears something of a false dawn, with chemical weapons having subsequently been used in the conflict on numerous occasions.

With even more frightening challenges ahead - genetic weapons for example and the existing disruptive power of cyber-weapons - a crisis in arms control is not good for anyone.

This year's Nobel Peace Prize highlights the importance of the lofty goals of disarmament even if Ican's treaty is unlikely to be any more successful in ridding the world of nuclear weapons than the NPT agreement before it.

- Published6 October 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published25 September 2017

- Published3 September 2017

- Published22 September 2017

- Published22 September 2017

- Published6 October 2017