Why do names matter so much?

- Published

When it comes to politics and international diplomacy, names matter. We know they matter because people are always changing them. Two important addresses changed this week.

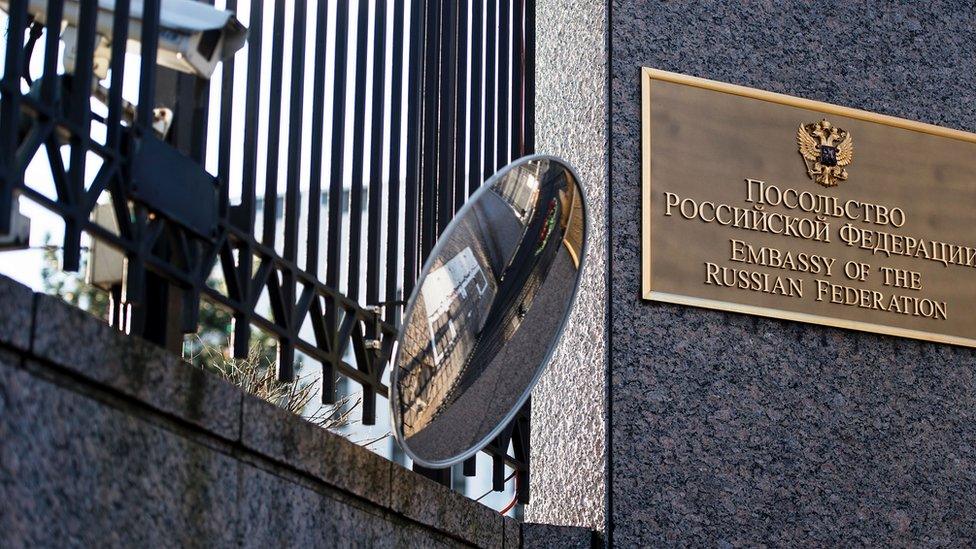

The Russian embassy in Washington found itself situated not on Wisconsin Street but Boris Nemtsov Plaza, named after a Russian opposition politician.

And in Turkey, the embassy of the United Arab Emirates is now on Fahreddin Pasha Road.

The Turkish situation was very 2018 in that it was the result of a Twitter feud.

The foreign minister of the United Arab Emirates, Abdullah bin Zayed al Nahyan, shared a tweet alleging that a century ago, the Turkish Ottoman military commander Fahreddin Pasha had mistreated Arabs while he was governor of the holy city of Medina.

The allegation was compounded by an accusation that ancestors of the current Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan were involved in the mistreatment too.

Mr Erdogan was not happy.

Turkish television carried footage of the street signs being changed

The minister should "know his place", replied the president, adding that he considered the United Arab Emirates spoilt by "money and oil". So now its embassy in Turkey sits on a street renamed after that long-ago governor.

"Good luck with it," added the mayor of Ankara, in a tweet, naturally.

One day later, in the US, the Russian embassy's official address changed from Wisconsin Avenue to Boris Nemtsov Plaza thanks to legislation championed by DC council members Mary Cheh and Phil Mendelson.

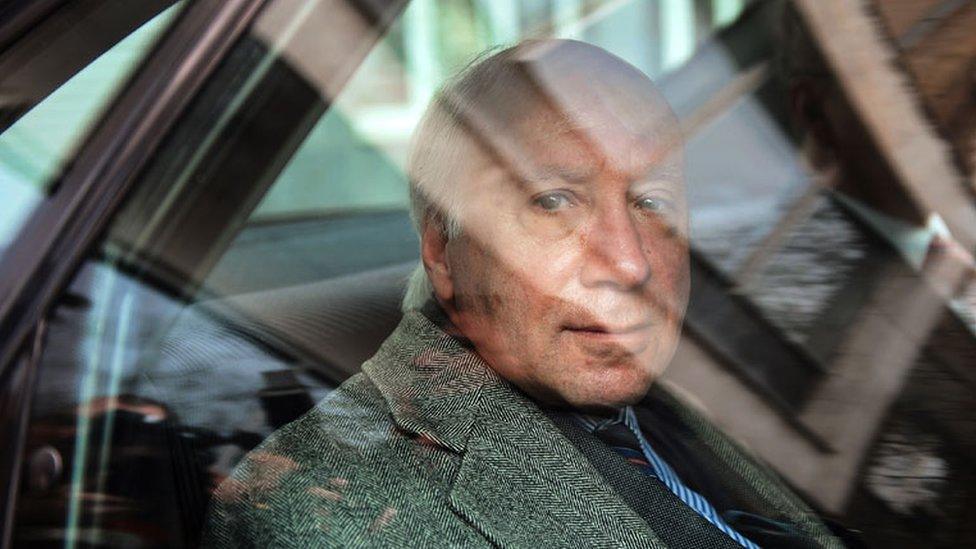

Mr Nemtsov was an opposition politician, murdered outside the Kremlin in 2015.

One politician in Moscow called the name change "a dirty trick".

A fierce critic of Vladimir Putin, Boris Nemtsov was fatally shot near the Kremlin in 2015

These are just the latest examples of the centuries-old recognition of the power and importance of names.

If you search online for the address of the United Kingdom embassy in Tehran, Iran, you'll be told that it's 198 Ferdowsi Avenue.

Iranians got good at changing names in the early 1980s. Thousands of streets and buildings named for the regime of the deposed shah were instead dedicated to mark the Islamic revolution.

In what was originally a prank, a group of students changed the signs where the British embassy was located to read "Bobby Sands Street", after the high-profile IRA activist who died in prison on hunger strike while serving a sentence for firearms offences.

Weirdly, the name stuck. So instead of having an official address which memorialised someone who considered the British state the enemy, British embassy staff decided to start using the back door instead, thereby changing their postal address.

And as Ferdowsi is considered to be the Persian national poet, perhaps they reasoned a street named after him was safe from being changed.

If renaming streets is controversial, renaming whole countries is critical.

You don't hear the phrase Upper Volta on the BBC any more. Burkina Faso - or land of the upright people - tells us that this is a country no longer colonised by another nation - the French - who decided that the best way to denote the territory would be a purely geographical one.

The break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s revived the idea of Macedonia as a nation. But Macedonia is also the name of the bordering region of Greece. So what to call the new country?

Independent Macedonia? Republic of Macedonia? Negotiations over the use of the name have been going on ever since with little sign of a breakthrough - until now.

Matthew Nimetz is hopeful that Greece and Macedonia can settle their naming dispute

Earlier this week, Matthew Nimetz, the UN envoy who's been trying to resolve the issue for more than two decades said he was hopeful they were now moving towards settling the dispute.

So the clock may be ticking for "the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", or FYROM, the inelegant fudge which has been used in the meantime.

Names matter whether you're talking about a street, a country or a human being.

When he became a Muslim, it meant a lot to Cassius Clay that he be known to the world as Muhammad Ali.

It took six more years until US newspapers stopped calling Ali by what he deemed his "slave name". And the reason we attach so much importance to names is that they tell the world something about us.

It can be something unique. Brazilian footballers traditionally go by nicknames. Edson Arantes do Nascimento means almost nothing. Pele means everything.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento, aka Pele

That's despite the man considered by some to be the greatest ever football player saying in his autobiography that he has no idea where the name came from.

So there's power in choosing a name, power in changing it, and - as both religion and mythology tell us - power in guarding it.

My partner and I are being assessed as prospective adopters at the moment. We've been told about the importance of identity to a child who has suffered loss and trauma.

We're told that changing a child's birth name, no matter how much you might dislike it, could be damaging.

Imagine having nothing but your name, and having that taken away by the new parents you were told would love and protect you.

In Jewish tradition, only the high priest in the Temple of Jerusalem was allowed to utter the four-letter name of God - and even then only once a year.

The Egyptian goddess Isis gained complete power of the sun god Ra when she learned his true name.

So what we call things can border on the magical. Names matter.

- Published10 January 2018

- Published9 January 2018

- Published2 August 2017