How I saw Stephen Hawking's death as a disabled person

- Published

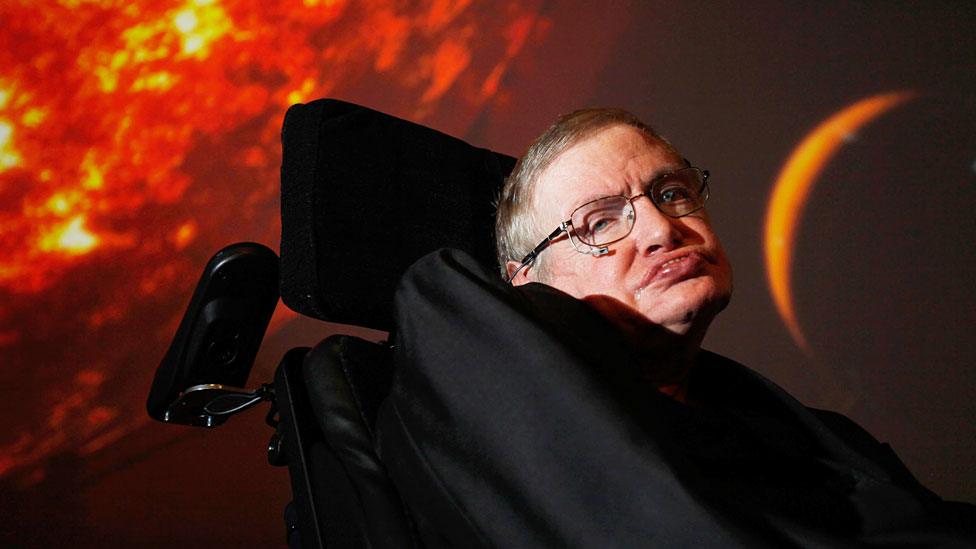

Stephen Hawking's work led many to become interested in astrophysics

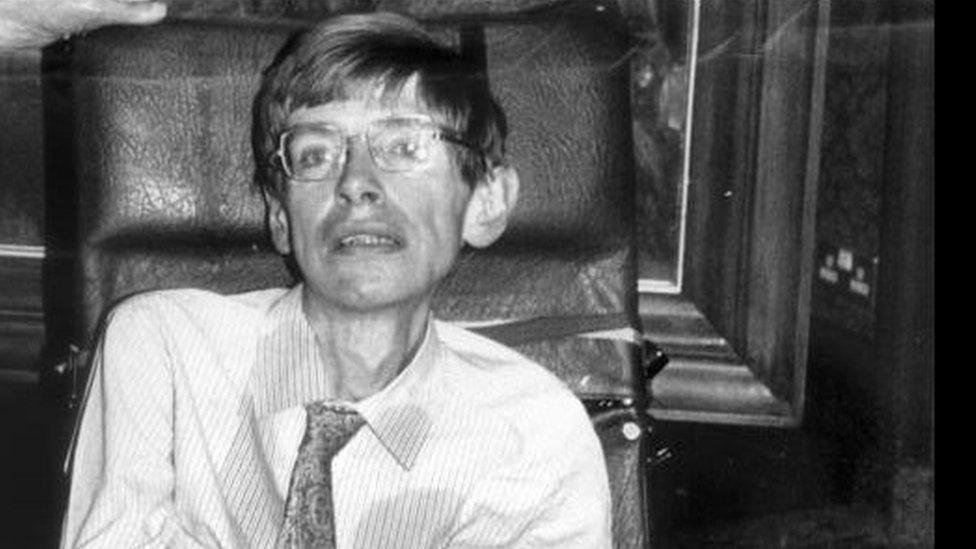

Stephen Hawking was a renowned scientist famed for his work on black holes and relativity.

He published several popular science books such as A Brief History of Time.

Prof Hawking was also a wheelchair user who lived with motor neurone disease from the age of 21.

Yes, he was an award-winning scientist, but a lot of the coverage after Prof Hawking's death has created a narrative of an "inspirational" figure who was "crippled" by his condition and "confined to a wheelchair".

As a disabled person, I've found this discourse troubling and somewhat regressive.

I'm tired of being labelled an 'inspiration'

Stephen Hawking's death has reminded me why I'm tired, as a disabled person and a wheelchair user, of being labelled an inspiration just for living my everyday life.

Prof Hawking was an extraordinary scientist and an incredibly intelligent human being.

However, many disabled people, myself included, would take issue with calling him an "inspiration" as this term is often used in popular society to belittle disabled people's experiences.

I am fine with my friends and family members calling me "inspirational". However, I get labelled it by random strangers, who hardly know me and just see the wheelchair and my condition (cerebral palsy, which means I use a wheelchair), not the person.

People with disabilities are often framed as either inspirational (say, a Paralympic athlete) or scroungers (people to be cared for or, worse, demonised) by the media and on television screens.

Our everyday experiences are neither heroic nor those of scroungers: it's just life as we know it.

More role models, please

Kids in the playground of my Merseyside primary school would compare me, probably the only young wheelchair user they had encountered, with the "genius" that was Stephen Hawking.

This was not an entirely fair comparison, I must say.

To me what this showed, even from a young age, was that there was a lack of "people like me", disabled people in the public spotlight, people I could aspire to be like.

I can think of four or five disabled people who were in the public spotlight when I was growing up early part of the last decade: David Blunkett, the former home secretary who is blind, Stephen Hawking, and two Paralympic athletes, Tanni Grey-Thompson and Ade Adepitan.

Stephen Hawking lived with motor neurone disease from the age of 21.

Prof Hawking showed that, despite public perceptions of what a disabled person can do, people with disabilities can achieve amazing things.

Even today, there are still too few disabled people out there in the public eye on a daily basis who are relatable for ordinary disabled people growing up.

If you're a sporty individual, there are Paralympic and disability sport stars. However disability representation on screen in the media and in society as a whole is low, despite the fact that disabled people make up almost one in five of the population, external, according to the UK government's Family Resources Survey.

All too often, they are categorised using able-bodied people's terminology as "inspiring" or "confined to a wheelchair" by illness or otherwise - rather than language based on their own experiences.

Watch your words (and your memes)

An Australian artist, Mitchell Toy, posted an image of Stephen Hawking leaving his wheelchair, which some say is offensive

For me, the most troubling moment in the reaction to Prof Hawking's death was when an image of him standing out of his wheelchair went viral on social media.

What this image suggested was a rather damaging trope: the disabled person should always seek to not use a wheelchair, rather than the impairment being something positive to reflect and work with.

Society still seeks to create an image of a disabled person's life as pitiable or a burden on society. This can be incredibly damaging to a disabled person's mental health and their perception of themselves.

Class matters

Prof Hawking was a fellow at Cambridge's Gonville and Caius College for 52 years

One cannot ignore the role of class, race and gender privileges when it comes to disability as these are often intertwined.

Prof Hawking was first diagnosed with motor neurone disease at the age of 21 and given a very short time to live.

However, prior to that, his experience had been one of an able-bodied upper middle-class male who studied at Oxford.

As my colleague Alex Taylor wrote for the New Statesman in 2014, Prof Hawking's social class and that he became disabled at 21 meant that he was afforded opportunities, external that would not have been given to a disabled person in his era who was born with their condition.

Often, the biggest barrier to a disabled person's advancement in society can be low expectations in the education system.

I grew up on Merseyside in northern England and went to a mainstream primary school and a comprehensive secondary school on a former council estate. I was sometimes advised to take "easier" subjects on account of my disability.

Fortunately, I persisted: I studied the subjects I wanted to. I went on to university and to get my dream job here at the BBC.

Dream unlocked: I recently reported for the BBC on Tube access in London

Only 44,250 of over 400,000 students declared a disability when starting their degree courses in 2015-16, external, the Higher Education Funding Council reported.

When you consider that there are 13.3 million disabled people in the UK, that's a very low number.

Social class is still a significant contributor to determining the life chances of disabled people, something that Prof Hawking's death has brought home for me.

- Published14 March 2018

- Published14 March 2018

- Published15 March 2018