Can English remain the 'world's favourite' language?

- Published

English is spoken by hundreds of millions of people worldwide, but do the development of translation technology and "hybrid" languages threaten its status?

Which country boasts the most English speakers, or people learning to speak English?

The answer is China.

According to a study published by Cambridge University Press, up to 350 million people there have at least some knowledge of English - and at least another 100 million in India.

There are probably more people in China who speak English as a second language than there are Americans who speak it as their first. (A fifth of Americans speak a language other than English in their own homes.)

But for how much longer will English qualify as the "world's favourite language"? The World Economic Forum estimates about 1.5 billion people around the world speak it - but fewer than 400 million have it as their first language.

Of course, there is more than one English, even in England. In the historic port city of Portsmouth, for example, the regional dialect - Pompey - is still very much in use, despite the challenges from new forms of online English and American English.

English is the world's favourite lingua franca - the language people are most likely to turn to when they don't share a first language. Imagine, for example, a Chinese speaker who speaks no French in conversation with a French speaker who speaks no Chinese. The chances are that they would use English.

Five years ago, perhaps. But not any more. Thanks to advances in computer translation and voice-recognition technology, they can each speak their own language, and hear what their interlocutor is saying, machine-translated in real time.

So English's days as the world's top global language may be numbered. To put it at its most dramatic: the computers are coming, and they are winning.

You are probably reading this in English, the language in which I wrote it. But with a couple of clicks on your computer, or taps on your tablet, you could just as easily be reading it in German or Japanese. So why bother to learn English if computers can now do all the hard work for you?

Do human translators have a long-term future?

At present, if you want to do business internationally, or play the latest video games, or listen to the latest popular music, you're going to have a difficult time if you don't speak any English. But things are changing fast.

In California, Wonkyum Lee, a South Korean computer scientist for Gridspace, is helping to develop translation and voice-recognition technology that will be so good that when you call a customer service helpline, you won't know whether you're talking to a human or a computer.

Christopher Manning, professor of machine learning, linguistics and computer science at Stanford University, insists there is no reason why, in the very near future, computer translation technology can't be as good as, or better than, human translators.

But this is not the only challenge English is facing. Because so many people speak it as their second or third language, hybrid forms are spreading, combining elements of "standard" English with vernacular languages. In India alone, you can find Hinglish (Hindi-English), Benglish (Bengali-English) and Tanglish (Tamil-English).

In the US, many Hispanic Americans, with their roots in Central and South America, speak Spanglish, combining elements from English and the language of their parents and grandparents.

English has changed since Chaucer's day

Language is more than a means of communication. It is also an expression of identity - telling us something about a person's sense of who they are. The San Francisco poet Josiah Luis Alderete, who writes in Spanglish, calls it the "language of resistance", a way for Hispanic Americans to hold on to - and express pride in - their heritage, even if they were born and brought up in the US.

English owes its global dominance to being the language of what until recently were two of the world's most powerful nations: the US and the UK. But now, especially with the rise of China as an economic superpower, the language is being challenged.

If you are an ambitious young jobseeker in sub-Saharan Africa, you might be better off learning Mandarin Chinese and looking for work in China than relying on your school-level English and hoping for a job in the US or UK.

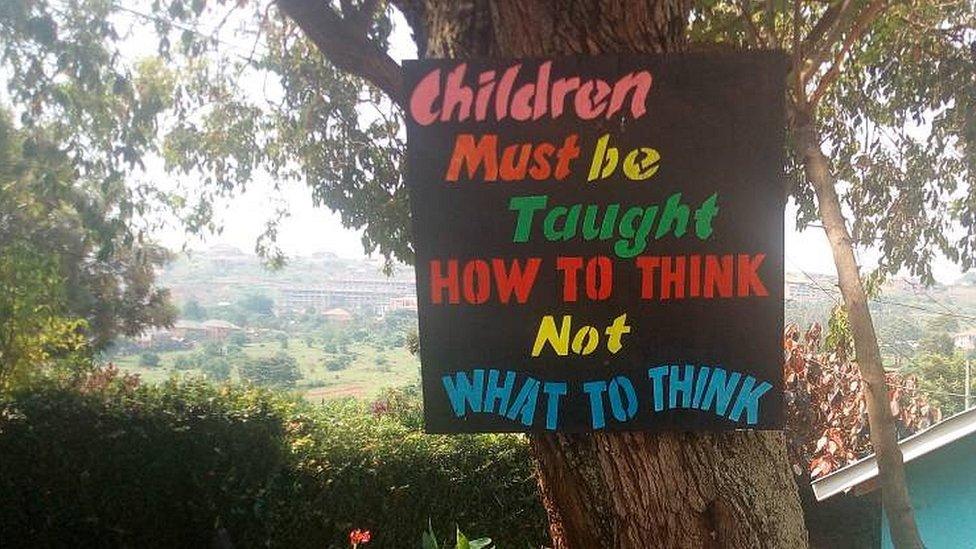

English is regarded in Uganda as a means of getting on in life

In the US itself, learning Chinese is becoming increasingly popular. In 2015, it was reported that the number of school students studying the language had doubled in two years and, at college level, there had been a 50% rise over the past decade.

In Uganda, however, all secondary schools must conduct classes entirely in English, and some parents teach their young children English as their first language. In many parts of the world, English is still regarded as a passport to success.

So is the future of English at risk? I don't think so, although its global dominance may well diminish over the coming decades. Like all languages, it is constantly changing and adapting to new needs. Until recently, "text" and "friend" were simple nouns. Now, they are also verbs, as in "I'll text you," or "Why don't you friend me?"

Computerised translation technology, the spread of hybrid languages, the rise of China - all pose real challenges. But I continue to count myself immensely fortunate to have been born in a country where I can cherish and call my own the language of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton and Dickens, even though the language I call English is very different from theirs.

Find out more:

Robin Lustig's four-part documentary series, The Future of English, begins on the BBC World Service on Wednesday, 23 May

You can listen online, on the BBC Radio iPlayer or download the programme podcast